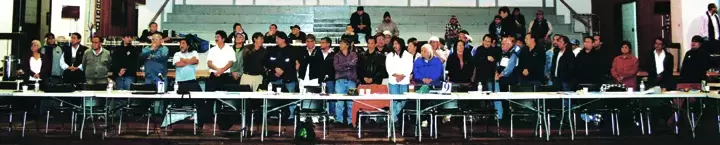

The hereditary chiefs of the Nuu-chah-nulth territories stood together on Jan. 19, the final day of the Council of Ha’wiih meeting at Maht Mahs, and spoke with one voice.

Their intention was to send a message to the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DF0) which said the Nuu-chah-nulth ha’wiih will take care of their resources within their ha’houlthees (chiefly lands), and they will ensure that their people get the fish they need.

“There is no way we are going to let our people starve,” said Ahoushat Tyee Ha’wiih Maquinna Lewis George.

The statement of solidarity sprang from DFO’s continued mishandling of the Aboriginal food and ceremonial fishery over many years, the ha’wiih told representatives from the department, and particularly from events last year when, despite the record runs of sockeye in the Somass and the Fraser River systems, some communities were only given a food and ceremonial allotment that would provide six sockeye for each of their members for the year.

The food and ceremonial fishery is a priority, which comes only after conservation in Canadian law. The commercial and sport fisheries come after the Aboriginal food fishery, and the ha’wiih told DFO that if commercial and sports fishers are out on the waters, then Nuu-chah-nulth will continue to be provided for and will have fish on their tables.

“We need you to know that come this summer we are not going to let those fish go by. We are not asking. We are telling you that we are not going to let our people starve. We have been too passive,” Maquinna said.

The problems surrounding the food and ceremonial fishery has persisted over many years, but came to a head last summer when DFO enforced what it calls an “adjacency policy.”

The Princess Colleen, owned by the Charleson family from Hesquiaht, is one of the few Nuu-chah-nulth fishing vessels working in the territories. It is often used by the nations to conduct their food fisheries. For example, when Yuu-tluth-aht needed to fill their food fish needs last summer, it was the Princess Colleen and her crew that fished for the nation in the Barkley Sound.

Skipper Con Charleson explained that the fish were so plentiful in the sound last year it took only one five minute drift set to catch more than what Yuu-tluth-aht required. The extra fish were distributed to other Barkley Sound nations.

But last summer when Ehattesaht, whose territory was deplete of the sockeye resource, wanted the Colleen to food fish for its members, DFO stepped in. It threatened the Colleen with seizure if it attempted to get Ehattesaht’s allocation from the bounty the Barkley Sound could provide.

The difference between Yuu-tluth-aht and Ehattesaht is that Yuu-tluth-aht has territory in the sound, but Ehattesaht has not. What that nation had, however, was permission from the ha’wiih of Hupacasath, whose territory is in the sound, to get the fish required to fulfill Ehattesaht’s food and ceremonial needs. The ha’wiih asked Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council President Wickinninish Cliff Atleo to speak on their behalf. Speaking in his language, Wickinninish said the ha’wiih have been taught how to take care of their resources. He explained that both traditionally and today, the ha’wiih of one nation does not go into the territory of another without permission and they respect this protocol. It is not uncommon for a ha’wilth to ask another to take some resources out of his territory and trade what was available within his own, Wickinninish said.

This is the time honoured tradition of the ha’wiih. It was offensive to the hereditary chiefs that DFO did not respect the ancient laws and protocols of the ha’wiih.

The ha’wiih then presented DFO with a set of principles by which they would stand.

1. In the absence of conservation restrictions, First Nation’s Food, Social and Ceremonial needs have priority over all other harvesters (Section 35 of the Canadian Constitution, and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples).

2. First Nations will define their Food, Social and Ceremonial needs seasonally based on the needs of their communities and the abundance of available resources.

(Another frustration for communities was that DFO was using population numbers from the mid-1990s to determine allocation. Hesquiaht’s population numbers, for example, have increased by 30 per cent since that time.)

3. First Nations prefer to harvest their Food, Social and Ceremonial needs from their own territories using their own fishermen. Harvesting will be monitored and reported.

(Resources in some territories have been so depleted through commercial over-fishing or destroyed by industrial activity that the ha’wiih wanted to know how DFO was going to work with Nuu-chah-nulth leadership to restore the territories, lost due to no fault of their own.)

4. If First Nations territories will not support their Food, Social and Ceremonial needs, then First Nations will enter into protocol agreements with other First Nations to meet their Food, Social and Ceremonial needs.

And,

5. First Nation’s protocols will be respected to ensure that the First Nations meet their Food, Social, and Ceremonial needs.

Brigid Payne , a Senior Policy Advisor with DFO. addressed the ha’wiihs’ statement. She said DFO acknowledges “the critical job of doing things better” in regards to the food and ceremonial fishery.

Food fisheries issues are not easy topics, she said. There were many factors that contributed to the food fish allocation.

When DFO enters into a food, social and ceremonial allocation it takes it as a solemn commitment to deliver that fish, she explained.

“And we will change the way we manage other fisheries to keep that commitment.”

There is recognition from DFO of the problems First Nations are having with access to the resources, she said. “We have heard the concerns and we take them seriously.”

Gerry Kelly, Acting Aboriginal Program Officer with DFO, told the gathering that what was missing from the relationship between DFO and Nuu-chah-nulth was the “time and space to have these discussions.”

“It seems as though we are always urgently reacting to issues.”

He said it was important to find some concrete ways “to identify and put into action some of the general principles to deal with things that cause us frustration.”

Kelly said what was needed was time to think, strategize, and effectively work together.

He said the adjacency issue was one that, in a timely way, Nuu-chah-nulth, through their Uu-a-thluk fisheries department, and DFO could sit down with the appropriate people and ask questions, not impose each other’s views, and learn the best way to achieve the interests of both parties.

But DFO’s comments only seemed to exacerbate the frustration in the room. It would seem, from all accounts, there would be no plan of action on the issues of concern to the ha’wiih that day.

NTC’s Fisheries Manager Dr. Don Hall said the issue was not as complicated as some would like to make it.

First Nations’ needs are a priority in law, he said. That is not being practised the way it should be.

“If there is a fishery, then there is no conservation concern,” he said.

DFO has put in place a restriction on First Nations to access the needed food and ceremonial fish, and it remained unclear why that restriction is in place, he said.

Huu-ay-aht Ha’wilth Hupinyook, Tom Happynook, had the day before suggested facetiously that DFO make all the commercial and recreational fishers harvest fish from waters adjacent to their own home territories, just to make things equitable.

Hall told DFO “We don’t need further meetings. We have all the right people in the room to make things happen.”

Tla-o-qui-aht’s Francis Frank described himself as a practical man, not prone to taking a strident tone. But he said it was difficult to work “when the other party doesn’t bring solutions to the table.”

“I’m looking for answers for this coming season. Our people want to know. We had trouble this summer because of your phantom policy. It’s something (DFO officers) are obligated to enforce.”

Frank directed his comments to members of the Nashuk Youth Council, who had earlier made a presentation to the ha’wiih and DFO about how important traditional foods are to Nuu-chah-nulth young people.

“All we’ve heard is platitudes this morning,” Frank told them. “We’ve had enough of that.” He said he really wanted the youth to understand that in Canada today it was not the ha’wiih that had the control anymore.

“We have to go to them to access fish, not the ha’wiih... (DFO) have control and they don’t want to let it go. They are talking about an adjacency policy. It’s a policy they created. Not the ha’wiih. The ha’wiih have their protocols. It isn’t that simple anymore because the control lies with the department... no matter how nice they speak to us this morning they come with no solutions...”

The ha’wiih, however, were making it clear that that situation wasn’t going to be allowed to stand anymore.

Carol Anne Hilton, who has been appointed by the Hesquiaht ha’wiih to the position of CEO of Rights and Title Coordination, told DFO they had two jobs—to conserve and to accommodate.

“Your limitations are not our problem.”

She told DFO that the ha’wiih will make their own access plan.

“Today we saw the re-insertion of ha’wiih into the access for food and ceremonial.”

The time and space DFO suggests and the organization’s acknowledgement that it needs to improve “expresses itself as infringement on the rights of our ha’wiih,” said Hilton, authority protected within Canada’s own Constitution.

She said all conditions, restrictions and limitations on Nuu-chah-nulth food and ceremonial access is an infringement on the ha’wiih.

“It is this infringement that is an insult to our ha’wiih, on the responsibility to provide for our people.”

The ha’wiih will make an access plan based on the current numbers of Nuu-chah-nulth people and not the outdated DFO numbers, she said, adding DFO should expect and plan for food and ceremonial access by ha’wiih authority.

“We have equipped our boats with nation-to-nation protocols. DFO needs to educate itself on this equipment.”