A pair of Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations are partnering with Strathcona Regional District (SDR) in a tsunami modelling project designed to improve safety in the event of a megathrust quake.

The $450,000 coastal risk assessment for northwest Vancouver Island — Gold River to Cape Scott — is one of 24 provincial emergency preparedness projects for which funding was confirmed in early July. Nuchatlaht and Ka:'yu:'k't'h'/Che:k'tles7et'h' each receive $150,000 for the survey, expected to get underway as early as August under regional district management.

“I don’t think there’s a more important project the SRD can undertake for the communities on the west coast other than filling in this tsunami gap,” said Shaun Koopman, protective services coordinator with the regional district.

Every community involved wrote a letter in support of the tsunami mapping project, which will encompass fully half of Vancouver Island, including Mount Waddington Regional District.

“In my opinion, this is going to be huge for communities on the west coast that don’t often get that level of support,” Koopman said.

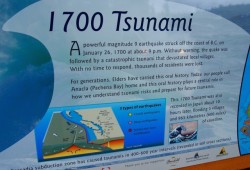

No such survey of this scope and magnitude has been done despite the region’s close proximity — no point of land comes closer — to the Cascadia Subduction Zone. The zone is a collision point of tectonic plates that last wrought disaster for Nuu-chah-nulth peoples along the coast in the year 1700.

In its grant application, the SRD pointed to a dangerous vulnerability.

“From an emergency planning and impact assessment perspective, the lack of relevant data diminishes the ability of public entities to adequately plan and prepare for such events,” states an SRD staff report on the matter.

A similar wave-modelling project for the Capital Regional District is nearing completion.

The inclusion of Indigenous knowledge — through direct experiences of the 1964 Alaskan quake tsunami and inherited cultural memory — will add to a technical/scientific data base, Koopman noted.

“What did they remember from that wave?”

No lives were lost on Vancouver Island during that overnight disaster 56 years ago, a remarkable outcome considering the extent of property damage in Port Alberni and Hot Springs Cove. Residents fled for their lives in the darkness, some clinging to their children. Emergency planning since that time has been based on the worst-case scenario of a 20-metre wave sweeping the coastline. For the purposes of analysis, the mapping will be based on peak “king tides” under present conditions and those possible under a one-metre sea level rise predicted by 2100. King tides are exceptionally high tides.

Nuu-chah-nulth storytelling, fossil records and historical Japanese recordkeeping provide clues to what has occurred in the past. Large, prehistoric tsunami sites along the west coast have been identified through geology. These include sites in the territories of every nation from Huu-ay-aht to Checklesaht.

Earthquake Early Warning Sensors, land based and on the sea floor, have been installed in recent years, but there remains a considerable gulf in understanding the physics of coastal flooding, the so-called “tsunami gap.”

Drawn from aerial LiDAR and bathometric (sea floor) surveys in combination with inshore data from buoys and shoreline, the mapping will inform emergency planning and safety recommendations in the long term.

“Stronger recommendations stem from good data,” Koopman said.

The mapping project is slated for completion next summer. A memorandum of understanding between the three nations involved and the SRD opened the door to the initiative.

“Tsunamis are a real threat to people’s safety and way of life on the North Island so I’m pleased to see this funding will support the development of a coordinated tsunami response,” said Claire Trevena, MLA for North Island. “Our government is equipping communities with the tools they need to prepare for and respond to flooding events.”

Emergency preparedness funding also goes to Tahsis for a flood mitigation preliminary design project and to Zeballos for a slope-hazard mitigation study.

Zeballos has been faced with a potential slide after wildfire swept across the face of a mountain by the village in 2018, forcing temporary evacuations. An engineering report determined that some habitable structures east of Maquinna Avenue are “exposed to hazard and risk levels greater than what is generally considered acceptable by society.”

The study will assess the appropriateness of potential mitigative options, said Mayor Jule Colborne.

“Safety of the public is our top concern,” she said.

The unstable mountainside is on Crown land, not within the village, which was the factor that ultimately determined the funding. One home remains vacant until mitigation measures can be worked out.

Once mitigation options have been confirmed, the village will seek funding to do the actual work, either through Emergency Management B.C. or the federal government.

“This is just one more piece in the puzzle,” Colborne said.