Joe David has been studying Nuu-chah-nulth art professionally for over 50 years. It’s a craft he has dedicated his life to and yet, the master artist still struggles to describe the region’s visual signatures.

“It’s not something that I have found easy to explain in words,” he said.

Using visual references from a selection of drums, masks and paintings, David explained the free-form nature of his craft while filming a video in conversation with Gordon Dick at the Tofino Botanical Gardens. The segment is among the programming slated to premier at the Carving on the Edge Festival later this month.

Likening Nuu-chah-nulth art to calligraphy, David said the shapes and forms are built with thin lines that swell and shrink in thickness. It is an illustration of the “power, beauty, grace, harmony, balance and co-existence,” his ancestors possessed and lived by.

“The same winds that curled the grass in a certain way, curled us in a certain way – our feelings and our thought patterns,” he said. “We are nature. We’re not something from outer space.”

To accommodate COVID-19 restrictions, the annual festival is hosting its programming virtually this year.

Running from March 26 to 28, participants will have access to a variety of online events ranging from language classes to carving workshops.

Dick, Nuu-chah-nulth artist and owner of Ahtsik Native Art Gallery in Port Alberni, will also be hosting carver-to-carver conversations with Kelly Robinson and Tim Paul.

Through the series of discussions, Dick aims to explore what makes Nuu-chah-nulth art stand-out among the variance in northwest coast art.

“It’s so subtle to the eye that you have to earn it,” he said. “You have to study and pay attention – really slow down and look at it with student eyes.”

Despite having worked as an artist for 26 years, Dick approaches his work and conversations with the masters from the lens of a learner.

While he is able to identify a Joe David piece from 20-feet across the room, he said “it’s somewhat challenging to put [the style] into words.”

“It’s a feeling,” he said.

Northern styles, like Haida, developed what is called “the formline system,” consisting of words like “ovoid” and “U-shape,” said David.

“We’ve never named those shapes,” he said.

Be it the soft webbing of a red snapper, or the hard edge of a sea urchin, the shapes are born from nature. It is a fine balance between hard geometric lines and soft ovals that compliment each other, explained Dick.

Entering its tenth year, the festival has been built on sharing and teaching Nuu-chah-nulth culture.

This year, chuutsqa L. Rorick is facilitating a two-hour live zoom session about the Hesquiaht language. The first hour will consist of three Hesquiaht elders and four language apprentices sharing their knowledge and experiences, followed by a one-hour language lesson.

Other events include, a one-hour instructional video for beginners and intermediate carvers hosted by Robinson Cook, a film-screening and artist talk with Hjalmer Wenstob, along with a live session where five carving artists of varying skill levels and backgrounds will join audiences from their studios to discuss current projects.

For David, the festival opens the doorway between students and masters.

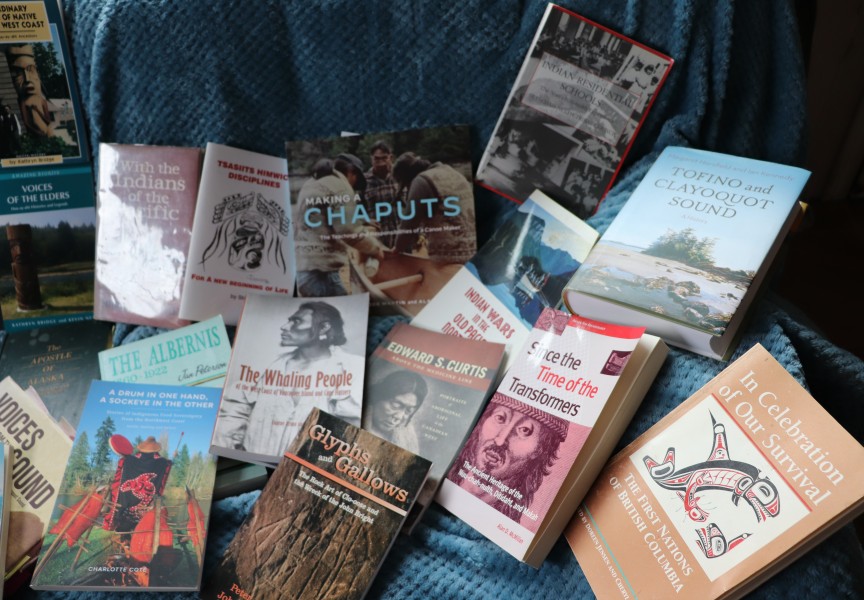

Like any art form, he encourages learners to study the old collections, to practice every day and to let-go of their egos.

“It’s a big brick wall that will only do damage,” he said. “Ego will cripple them and hold them back.”

While David also creates modern art paintings and drawings, he has focused on traditional Nuu-chah-nulth art out of respect for his ancestors.

“For hundreds of years, they developed this art form and its traditional form,” he said. “They deserve their contribution and their intelligence to continue and to be available.”