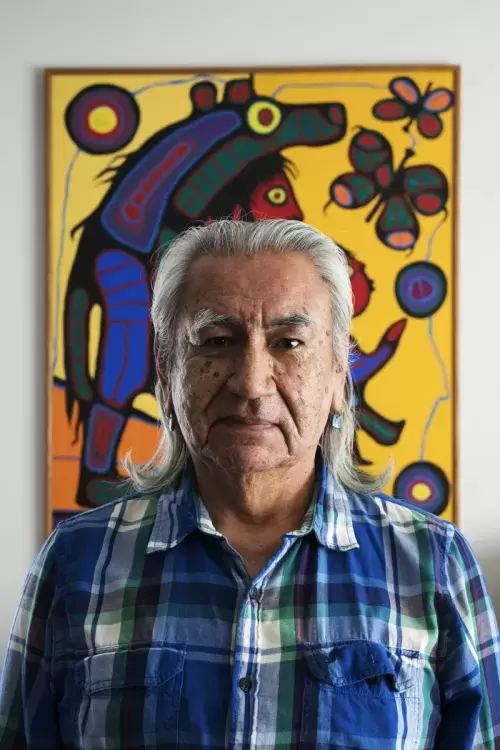

Born inside the house his grandfather built on Meares Island, Joe David was only moments old when his grandmother said, “this boy is going to be an artist.”

It wasn’t until decades later when David was working as an artist that his father recounted him the tale. Unbeknownst to David at the time, his parents had consciously raised him to support his creative journey.

If an artist was attending a gathering, David’s parents made sure he came in contact with them. Placing him in their arms, he became “part of that energy.”

From the time he could hold a stick or pick up a pencil, David was always drawing. Be it in the sand, or on the walls of his family’s home, he was as relentless as his parent’s encouragement.

David’s father, Hyacinth, who was a carver himself, continually strived to prop David up and support his artistic instincts.

Instead of asking him to “stop,” when David would draw on the walls, Hyacinth asked questions about the meaning behind the designs, David recalled.

Now, you can find David’s work exhibited all over the world and within the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

The 74-year-old has dedicated his life’s work to traditional Tla-o-qui-aht and Nuu-chah-nulth art forms in honour of his ancestors.

From the elegance of a cedar tree as it dances in a windstorm, to the symphony of waves crashing against the coastal rocks, David said his ancestors were such masterful artists because their souls were born from nature’s grace.

Everything from the carvings, to the songs, to the dances, to the language was translated from nature, he said.

“And also their relationships,” said David. “They adopted wolves as their main teachers in social order because they’re the most social animals in all of nature along the coast.”

As society becomes increasingly connected to the digital world, our relationship to nature has changed.

While Nuu-chah-nulth art has morphed in reflection of these changes, David said his development as an artist came from “the fact that I have applied myself seriously, and with respect and passion every day.”

Likening his craft to calligraphy, David said the shapes and forms of Nuu-chah-nulth art are built with thin lines that swell and shrink in thickness.

“Professional calligraphers practice over-and-over-and-over, like a pianist or a dancer would practice a movement over-and-over-and-over,” he said. “In the end, you’re going to have a much more graceful outcome than if you use a machine.”

Now semi-retired, David said the future of traditional art is in the hands of younger generations.

“Those past generations of master carvers and artists deserve respect [for] their efforts and accomplishments,” he said. “It should not end with them.”

Back in the tiny village of Opitsaht, David was sent to residential school when he was eight.

Stripped from his parents, drawing transported David out of his body into a world outside the school’s walls.

“I had that controlled world of my own,” he said. “It didn’t involve anybody else. I could be invisible.”

In between walking along the beach or heading out into the bush to be by himself in nature, David spent time inside the school’s chapel.

“I could go in there and be left alone,” he said.

The quiet space became his refuge. It was a place where he could draw, dream, or observe the carvings of Jesus, Mary and the crucifixion.

Uninterested in running races or playing ball games, David was a quiet, introverted child – characteristics he continues to identify with today.

He attended Christie Residential School for three years before his family moved to the United States, where he made it to Grade 9 before dropping out.

For the then-teenager, he said his time was much better spent working and got a job at a lumber mill in the Olympic Peninsula, in Washington.

On trip back to Seattle to visit his family, he heard about a government-funded art program through Job Corps, which he wasted no time applying to.

Within months, David began a two-year commercial art program in Texas, that covered a variety or disciplines, from painting, to drawing, to photography.

It wasn’t until he completed the program that his interest in Northwest Coast art began to take shape. Fortuitously, the skills he had developed as a silk screen printer and sign painter seamlessly translated into the style.

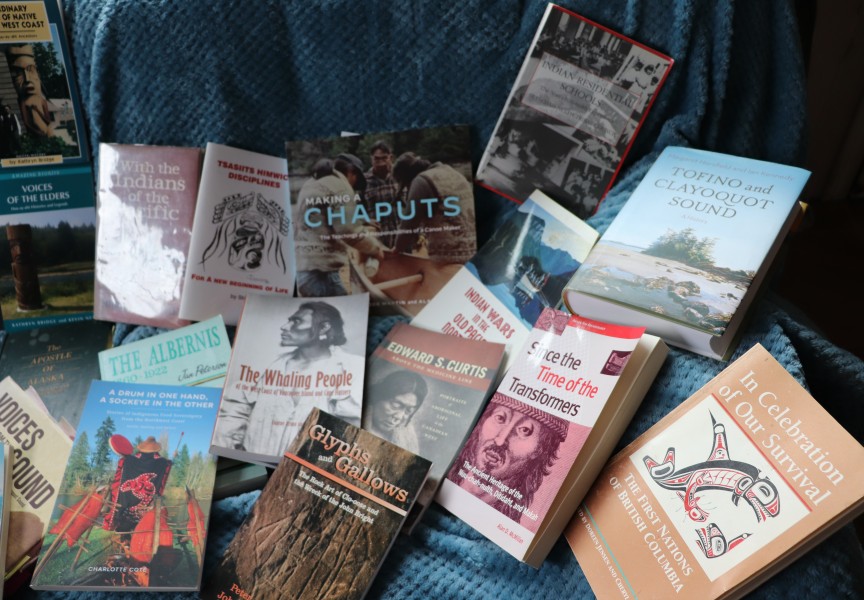

At the time, there weren’t many resources for David to draw upon, so he began frequenting Shorey, the only bookstore in Seattle that carried a handful of books on the topic.

While visiting one of Shorey’s satellite locations in 1971, David stumbled upon a non-Indigenous man carving a totem in the middle of the Seattle Center.

Wearing a red bandana that kept his long, black hair neatly parted, David watched with fascination.

Duane Pasco, who has played a major role in the re-emergence of Northwest Coast art by working as a creator and teacher since the 60s, invited David to his home.

“Man, I was there in a heartbeat,” he said. “I would show up every day. I started to carve beside him and learn.”

Through Pasco, David was introduced to the late Bill Holm.

His book, Northwest Coast Indian Art, is what “we call the bible,” he said. “It explains the Northwest Coast northern formline system.”

At the time, Holm was teaching at the University of Washington and allowed David to sit in on his classes.

“He showed slides of Northwest Coast art,” he said. “Masks, carvings, totem poles – everything. He was an amazing teacher and it was because he was a practicing artist himself. He was one of the most amazing artists and carvers in the traditional forms I’ve ever known.”

Within a few years of completing his commercial art program, David began selling his masks to Seattle-based gallery, The Legacy Ltd. Dropping off new pieces at least once a week, the steady sales allowed him to live comfortably, while continuing to work on his craft every day.

After spending four years learning and working alongside Pasco and Holm, David left the Seattle area in 1975 to return home, to B.C. west coast.

In order to follow in the footsteps of his ancestors who had developed the Tla-o-qui-aht aesthetics of Northwest Coast art for thousands of years, David said he needed to return to the place it originated from.

“I wanted it to have the heart and soul that it deserved,” he said from his home in Ty-Histanis. “And that meant being here.”

Since then, the master artist has come and gone, always returning to his traditional territory.

In 2018, a totem pole that David carved in honour of the Tla-o-qui-aht hereditary chiefs was erected in Tofino. Standing in view of his birthplace, the village of Opitsaht floats in the background. It is meant to serve as a constant reminder of Tla-o-qui-aht’s history and the hereditary chief's spiritual and physical stewardship of the hahoułee, known as traditional territory.

Historically, Nuu-chah-nulth peoples did not have written words.

“We had carved forms and paintings,” said David. “It’s no different than a great piece of literature.”

Much like he did in the early years of his career, David continues to work at his craft by applying himself every day.

It’s a practice he urges younger generations to follow, which requires studying the old pieces of art, he said.

“Fortunately for people today, there are dozens of books,” he said. “But you really need to see [the art] in person.”

Going to museums and making contact with the old pieces is critical, he said.

“The masks and headdresses were danced,” he said. “They had movement, which reinforced their life force. Standing in front of them can help you imagine these things being danced in the light of fire.”

Despite studying traditional forms for over 50 years, David has no plans to stop anytime soon.

“I do it out of respect for the ancestors,” he said. “So that the heart, soul and spirit of their art lives on.”