Most families from Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation had four totem poles displayed in front of their homes before European settlers arrived on the west coast in the late-1700s.

When a woman married into a tribe, a totem pole was raised to depict her family’s history. It would stand next to three poles. One for her husband’s history, another for his parent’s history and the fourth for his grandparent’s history, according to teachings given to Joe Martin, master carver and Tla-o-qui-aht elder.

For Tla-o-qui-aht families, the totem poles served as daily reminders of the teachings relatives were expected to uphold.

“It’s our constitution,” said Martin. “Teachings of natural law.”

200 homes burned

Today, only two totem poles from 1989 and 1993 remain in Opitsaht on Meares Island – one of which is rotting and leaning to the side, said Martin. This is why his eldest brother, Nookmis, asked Martin to carve a new totem pole for the ancient village.

As Europeans first arrived in the Clayoquot Sound and encountered the Tla-o-qui-aht, they couldn’t make sense of the totem poles, said Martin.

Just like First Nations couldn’t read English, Martin said settlers couldn’t read the totem poles.

“They were also illiterate,” he said.

Totem poles are not read linearly. Often carved as animals or mythical creatures, the crests hold ancient teachings that change with the seasons, said Martin. Passed down through the generations, each one tells a familial story or serves to honour a specific event, or person.

Shaped as guiding principles, the teachings were often taught through song and dance, said Martin.

As an example, Martin pointed to a sea serpent and said it represents the lightning in the sky.

“It’s a teaching about being quick,” he said, recalling his ancestors who used to hunt whales. “They had to be.”

In 1792, American trader Captain Robert Gray set fire to around 200 homes in Opitsaht, along with all the totem poles that stood beside them.

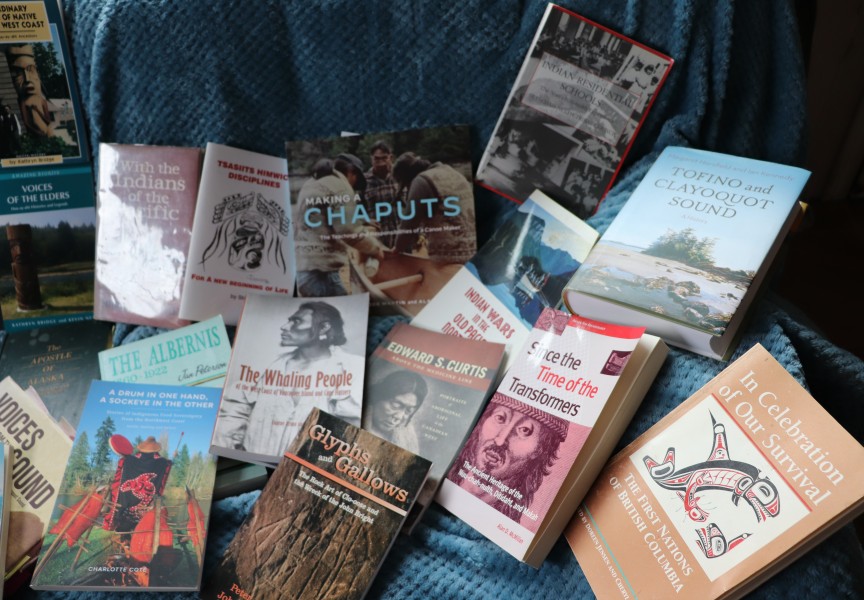

John Boite, one of the crew members who was ordered to burn the houses, described the village as “a work of ages,” in his diary, according to Tofino and Clayoquot Sound: A History by Margaret Horsfield and Ian Kennedy.

Around a century later, many totem poles were removed from Opitsaht.

The Indian Act was passed by the federal government in 1876. It aimed to eliminate Indigenous culture, with the goal of assimilating First Nations, Inuit, and Métis into a Eurocentric society.

Between 1884 to 1951, potlatches were banned in an amendment to the act. The law provided a framework for government officials and ethnologists to remove totem poles, as well as other cultural items, such as longhouse murals.

Some of the only remaining relics carved in the traditional Tla-o-qui-aht style can be found at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago.

According to the museum, the seven poles on display were carved by Shi-yus, chief of Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation, in 1890.

Ethnologist Charles Newcombe acquired the poles for the Field Museum in 1904 on a collecting expedition in the Pacific Northwest. Based on the museum’s records, they were sold to him by Shi-yus’ brother, Wickaninnish III, who had become Christian and acquired the name Joseph.

Martin said he has never seen the totem poles in person but keeps two images of them hung in his workshop in Tofino.

Even though they’re no longer on Tla-o-qui-aht’s traditional territory, Martin said that, in a way, he feels grateful because they’re still around today.

Carving to remember pandemics

A year and a half ago, Nookmis asked Martin to carve a new totem pole for Opitsaht. As the head of their family’s house of Ewos, Nookmis wanted it to be carved in remembrance of “the pandemic we all faced together,” said Martin.

Among other crests, four skulls are carved into the lower mid-section of the totem pole. One represents the most recent COVID-19 pandemic, another symbolizes past pandemics Nuu-chah-nulth peoples have endured, including smallpox and tuberculosis, the third skull honours all the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG), and the final skull recognizes all the children who never returned home from residential school, said Martin.

With the help of various local artists, including Gordon Dick, Patrick Amos, Robin Rorick, Ken Easton and Nookmis, Martin began carving the totem pole on June 18.

For Rorick, the process has been a journey of healing.

The Haida artist learned to carve while working on a totem pole with his late-cousin and mentor, Benjamin Davidson, around 2008. On Aug. 15, 2020, Davidson, a renowned Haida carver, suddenly passed from a heart attack. The loss continues to weigh heavy on Rorick’s mind.

“I think about my late-cousin every day when I work,” he said. “When I carve on the pole with Joe, it brings back good memories of time spent with my cousin.”

After a long year of being unable to socialize, Rorick said he has also found healing in being surrounded by other artists.

The totem pole is being crafted from an 800-year-old red cedar tree that was felled during the construction of the Canoe Creek Hydro project, on Tla-o-qui-aht territory.

Long ago, some totem poles used to stand at the entrance of a longhouse with an opening carved out for passage into the house, said Martin.

“You can imagine how big the trees used to be,” he said.

Despite standing 32 feet tall, Martin said this new pole would have once been considered small.

Part of the reason there aren’t more totem poles is that “it’s harder and harder to come by cedar,” said Rorick. “[These logs] are more and more rare.”

While some artists chose to carve totem poles independently, Amos said that the collaborative process allows artists to learn new techniques from each other.

“I love it,” he said. “You get to meet new friends – artists from other places and different territories.”

It’s a sentiment that Dick echoed by saying that it has been rewarding to learn from Martin.

“[Martin’s] path of teaching and sharing has been great to be around and a part of,” said Dick. “I’m always excited to have my student ears and student eyes on in regard to what Joe shares. [It] may not even be part of this totem pole. It’s just part of our history, part of our roots.”

A thunderbird is carved with its wings closed at the top of the totem pole to represent the nation’s female ancestry. For Martin, it was another way to honour the history of violence against Indigenous women. The crest of a moon sits on the bird’s chest, illustrating the nation’s first rule of law – “respect,” he said.

Martin scoffs at the phrase “low man on the totem pole,” which is commonly used to describe someone who is lowest in rank, or of least importance.

Rather, Martin said the bottom of a totem pole is one of the most important positions.

“It’s upholding all of the laws,” he added.

Rekindling culture and opening secrets

Martin said it’s undecided when the totem pole will be raised in Opitsaht. There are many preparations that need to be done in advance, including holding a potlatch ceremony.

After enduring many recent losses, including the death of Chantel Moore, who was fatally shot by an Edmundston police officer during a wellness check in June 2020, Martin said his family needs to release their pain before the totem pole can be raised.

As visitors, friends and family stop by the carving tent set up at the Tofino Botanical Gardens, Martin said a conversation has been sparked.

The totem pole has opened a space for people to learn about local histories, heal from the pandemic, honour ancestral teachings, remember the MMIWG, and commemorate the children who never returned home from residential school.

While cultural ceremonies and teachings were once forbidden, Martin said they no longer need to be kept secret.

“In a way, the totem pole helps to rekindle our culture,” said Martin. “To understand who we really are.”