A new report is highlighting the importance of restoring a focus on matriarchal roles for the health and strength of First Nations communities.

Published by the First Nations Health Authority (FNHA) and British Columbia’s Office of the Provincial Health Officer, Sacred and Strong: Upholding our Matriarchal Roles examines the health and wellness journeys of First Nations women and girls in British Columbia.

It is both a celebration of their strength and resilience, as well as an “urgent” reminder of the need for collective action to eliminate systemic barriers that disproportionately impact First Nations women and girls.

Rather than being a technical report filled with charts and data, it was a way to honour and respect the lived experiences of women by allowing them to highlight their self-determination and the health inequalities they face, said Dr. Shannon McDonald, First Nations Health Authority acting chief medical officer.

“I want Indigenous women to open this report and see themselves in it,” she said.

The report is intended to provide a new approach to tackle issues around health and wellness by empowering women to be part of the change. It is the first in what McDonald said she hopes will be a series of reports to measure that change over time.

“Traditionally, matriarchs taught girls and young women about respecting and caring for their bodies as well as about their nation’s customs with respect to pregnancy, childbirth and mothering,” read the report.

The passing of knowledge supported healthy child development within communities, it added.

As patriarchal laws were introduced to communities through colonialism, it “undermined and suppressed the active and respected roles of First Nations women,” read the report.

“When settlers came to [B.C], they didn't want to talk to women,” McDonald said. “They came from an extremely patriarchal system, and they placed men above women rather than [as] equal partners or having significant roles in the community. [Women] were really devalued by the settler communities. That’s been reflected in the Indian Act rules and regulations. And we've seen the negative impacts of that over time.”

McDonald said that in First Nations communities, there was a specific ceremonial, operational and cultural role for matriarchs. The cultural life of the community would centre on the experience, wisdom, and knowledge of the matriarchs, she added.

Forced surgical sterilization, the Sixties’ Scoop, the residential school system, and the child welfare system are some of the colonial systems and practices that disrupted teachings surrounding pregnancy, childbirth and mothering, the report suggested.

The residential school system “tore children away from their families” and told them it wasn’t okay to be who they are, said Ellen Frood, Alberni Community Women's Services Society executive director.

“Many [children] never saw their parents again, and many died,” she said. “Residential schools are not just a dark chapter in our history, they’re a legacy that continues to plague our Indigenous communities.”

In June, the Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights released a report indicating that until 1973, British Columbia had laws “requiring the forced and coerced sterilization of individuals who were considered ‘mentally defective.’”

First Nations, Inuit and Métis people were disproportionately targeted and sterilized, read the report.

It was assumed that the practice stopped with the changes to legislation in the 1970s, but the report indicated that cases of forced and coerced sterilization continued to be recorded, some as recently as 2018.

“Education is the heart of where we need to be,” said Frood. “The violence against Indigenous women and girls is systemic. It’s a national crisis and it requires urgent, informed and collaborative action.”

In First Nations communities, matriarchs are revered as knowledge keepers and storytellers, said Frood.

Now, their stories consist of being ripped away from their parents, she said.

“The knowledge keeping is of huge trauma,” said Frood.

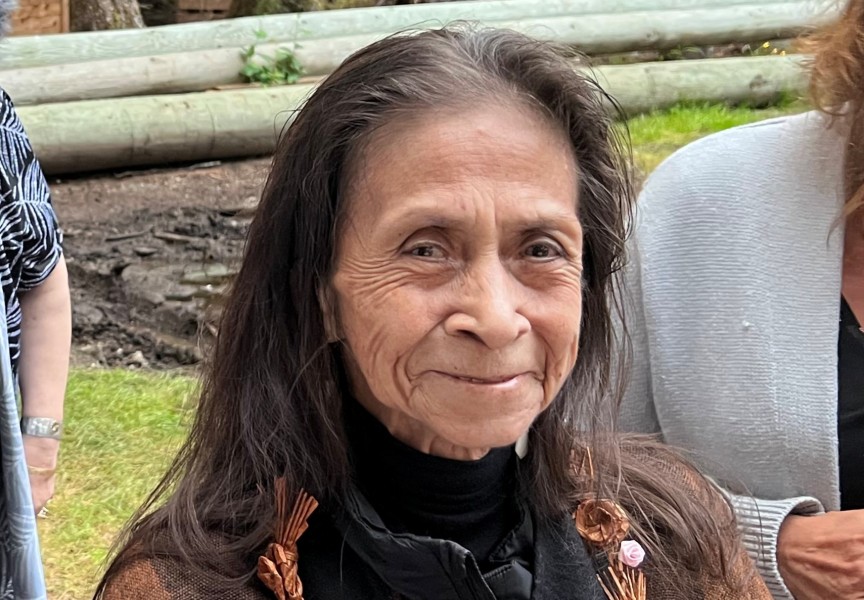

Ann Whonnoock is an elder from the Squamish Nation who was interviewed in FNHA’s new report.

“My hope for health care is that my family gets taken care of in a good way – that my grandchildren know they can go into a hospital and be given treatment that everyone else in the province gets and not be stereotyped because of who they are and where they come from,” she said in the report. “That they don’t face the troubles and traumas that my daughter faced by going into an emergency ward and being asked, ‘Do you drink? Do you use drugs?’”

Looking forward, McDonald said she hopes the women’s personal stories will engender conversation around topics such as how to approach Indigenous midwifery, steps to take in the event of a marriage dissolution and how to support elders who want to stay in community.

“It’s not western experts and academics taking the lead on what information is important and how it’s going to be used,” she said.

Instead, McDonald said the report prioritizes the stories of First Nations women and girls by allowing them to identify their own needs.

“It's just a really different way of telling the story than has been done in the past,” she said. “[It] responds to a really strong statement we hear all the time, and we try to honour – ‘nothing about us without us.’”