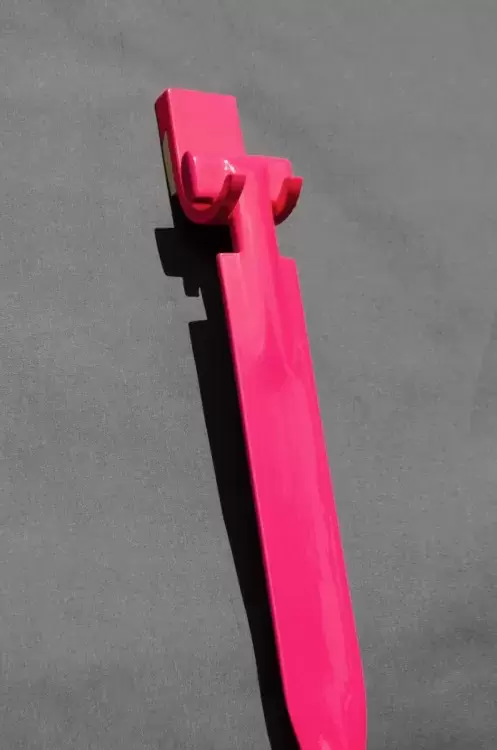

A sleek, hot pink paddle hangs on a wall inside the historic Mahon Hall on Salt Spring Island, off the coast of Vancouver Island. The art piece by Klehwetua Rodney Sayers is part of the Salt Spring National Art Prize’s 2021-2022 Finalist Exhibition.

The prestigious biennial competition and exhibition of Canadian visual art received 2,700 submissions, which were narrowed down to 52 finalists from across the country, and abroad.

Sayers was among them for the second time in the four years it’s been running.

“Hot Rod Pink” is a continuation of the Hupačasath First Nation artist’s ongoing series that playfully intersects First Nations art with his fascination of motorhead traditions.

The series is like a “hobby,” described Sayers, who regularly transitions his artistic practice between sculpting, metalsmithing and screen printing.

“I’m just trying to bring some humour and I’m trying to have some fun with it,” he said. “My mantra is, ‘if it's not fun, I don't want to do it.’”

While growing up in Port Alberni, Sayers became captivated by the ubiquitous street rods that roared through the city’s streets.

“I was fascinated with them as an object,” he said. “They were shiny, and the paint was fabulous.”

Only after Sayers heard them referred to as “muscle cars” for the first time did he realize the machismo culture that surrounded them. To Sayers, the cars were merely “beautiful objects and sculptures” – much like traditional Nuu-chah-nulth paddles.

Ronald Crawford, Salt Spring National Art Prize founding director, said Sayers was one of the first artists he knew of that “combined contemporary concerns and First Nations iconography together.”

“He uses pop culture and elements of mainstream Canadian culture and combines it with his own First Nations roots and upbringing,” said Crawford. “That's personally what I've found to be the most unique about Rodney's work.”

After graduating from the Alberni District Secondary School in 1981, Sayers drifted between Banff and Whistler as a self-described “ski bum” for over a decade before he knew it was time to switch gears. He never had any ambition to become an artist. Rather, he was focused on becoming a better communicator to utilize the knowledge he had been given by his teachers.

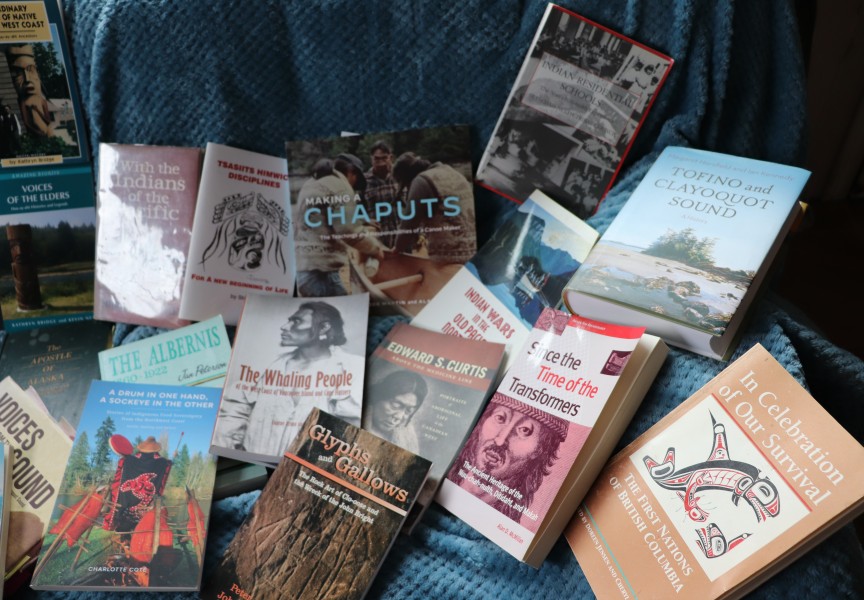

Throughout his childhood, Sayers spent a lot of time with elders and family members from Hupačasath and the surrounding Nuu-chah-nulth nations. At formal gatherings and feasts, he listened to the “old people talking” for countless hours and said he developed a deep appreciation for the command of oral history.

Although he was never taught his language as a boy, that connection to his relatives and ancestors provided him with a rudimentary understanding.

Art came into focus as a way to contribute to the “traditions of history keeping,” he said.

In 1992, Sayers traded in his snow pants for textbooks to begin a two-year studio arts program at the former Capilano College.

“I was trying to acknowledge and be grateful to the teachers who helped me,” he said.

He went on to study jewelry making at the Alberta College of Art and Design in Calgary, where he learned meticulous hand skills.

When working with jewelry, he said, a tenth of a millimetre is your margin of error.

“I learned to see things differently,” said Sayers. “That went into my printmaking, that went into my sculpture, and that went into my thought process.”

Sayers carried on to complete a masters in fine art metalsmithing at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design before returning home to Port Alberni.

In the early 2000s, he joined the Hupačasath language advisory group where he spent over 10 years working on language preservation by recording the remaining fluent speakers “until they all left,” he said. Through their teachings, he learned how to read, write and orate the language.

That work kept him in Port Alberni, where he continues to live today.

Sayers said that people often look at Hot Rod Pink and say, “it’s not traditional.”

“How people want to describe or categorize my work is of no concern to me,” he said. “The tradition is embedded in the work. It may not look traditional, but art making is a tradition … and tradition has to evolve.”

Oral language and Nuu-chah-nulth motifs, such as the thunderbird, are layered into his art.

“If you can read it, it will tell you many things,” he said. “It'll tell you secrets. It will tell you about the artist. It will tell you about where they're from, or what they're thinking about. Or it might tell you nothing if you can't read it or have no interest in reading it.”

When he becomes discouraged or grows tired, Sayers said he holds on to the words of the late-Jessie Hamilton and the other fluent speakers he worked with as part of the language advisory group.

“They said, ‘you have to keep using our language and making your artwork because you need to keep reminding people that we’re still here’,” he recounted. “I want people to see the work and hopefully it will speak to them on some level where they can be lifted up.”

While Sayers’ work has evolved over the years, his intention has remained constant.

“The materials inform my work,” he said. “The art-making tradition of the Nuu-chah-nulth people informs my work, the teachings from my advisors, my chiefs, and elders inform my work, the language informs my work, the land informs my work and the environment. It’s a language of contemplating all of those things and trying to capture them, even in small glimpses.”

The exhibition on Salt Spring Island is running until October 25 and the award winners will be announced at a gala night on October 23.

Of the 52 finalists, Crawford said 12 First Nations artists are represented.

For Sayers, making art is not only a “great privilege,” but an empowering tool for change.

“I really believe that artists are going to lead the world into the future,” he said. “I believe that creative solutions have to come to the forefront to resolve our problems of climate change, of racism and all the social problems that are real.”