Ron Hamilton first stepped into the Northwest Coast Hall inside New York City’s American Museum of Natural History 55 years ago, but as he walked through the gallery all he saw was “a massive trophy case.”

“It’s the biggest colonial trophy collection in the world,” he said.

The renowned Nuu-chah-nulth artist and cultural historian goes by his Indigenous name, Ḥaa’yuups. Despite his complicated relationship with the gallery, he has been working as its co-curator for five years – alongside Peter Whiteley, the museum’s curator of North American ethnology.

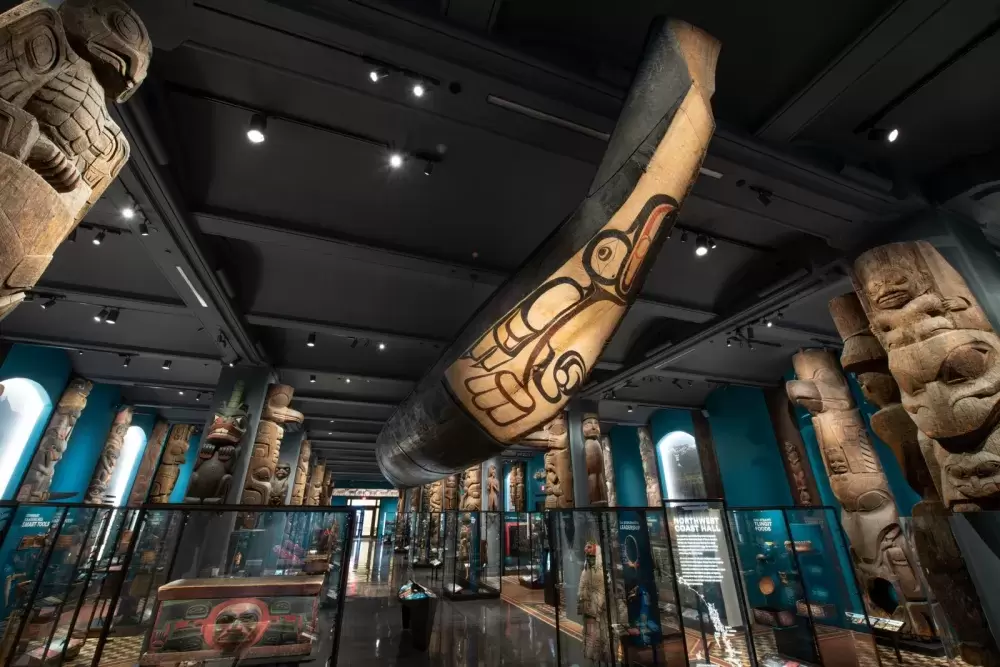

It has been over 120 years since the Northwest Coast Hall has been revitalized and is set to reopen to the public on May 13.

The hall is the museum’s oldest gallery, which was installed in 1899 by anthropologist Franz Boas.

At the time, it was standard for museums to place Indigenous people at the bottom of an evolutionary hierarchy – and place Europeans and Euro-Americans at the top, said Whiteley.

Boas aimed to deliver a “much more equitable representation of Indigenous cultures” by highlighting individual communities within a specific region, instead of displaying items based on their function.

Boats were no longer placed with other boats – rather, Nuu-chah-nulth objects were displayed with other Nuu-chah-nulth objects.

It was “absolutely revolutionary,” said Whiteley.

Yet, it lacked a “full-bodied presence of Indigenous voices and perspectives,” he said.

The updated hall aims to address this by collaborating with Ḥaa’yuups, and nine other consulting curators from First Nation communities across the northwest coast.

Over 1,000 works of art are displayed in the revitalized hall, including a Nuu-chah-nulth ceremonial wolf curtain which stretched more than 37-feet, and a 63-foot-long Northwest coast canoe – the largest in existence.

As Ḥaa’yuups reflects on the experience of updating the hall, one word comes to mind: “frustrating,” he said.

“I felt that my role was more token than I had hoped,” Ḥaa’yuups said. “A curator is involved in planning, restoration [and] stabilization. My involvement in those areas was absolutely minor.”

In some ways, Whiteley said he can empathize with Ḥaa’yuups’ frustrations.

“We have a large exhibition department, there is an outside design firm, [and] there is the conservation department,” he said. “I've often felt as the curator that I should have some greater ability to contribute to this than I think I've been getting. And that's been compounded by COVID-19.”

In his role, Ḥaa’yuups said it was important to address the history of racism in North America.

“Racism is what allows much of that material to be there,” he said.

While the museum may “possess” the cultural items on display, Ḥaa’yuups said that everything in the gallery still belongs to the “groups [of people] they were taken from.”

When the Indian Act was passed by Canada’s federal government in 1876, it aimed to eliminate Indigenous culture, with the goal of assimilating First Nations, Inuit, and Métis into a Eurocentric society.

Many of the Northwest Coast Hall’s artifacts were acquired between 1880 and 1910 during the potlatch ban, which was legislated under an amendment to the act, said Whiteley.

The law provided a framework for government officials, ethnologists and anthropologists to remove totem poles and other cultural items, such as longhouse murals.

Many of the confiscated items ended up in “these massive collections in institutions in the major cities of the world,” said Ḥaa’yuups.

The full stories and the meaning behind each object will never be known until “they’re returned to their communities of origin,” he said.

Whiteley said the museum's priority for international repatriations has been human remains and funerary objects.

Almost all of the human remains from Haida Gwaii were repatriated in 2002, along with some funerary objects. There was a follow-up repatriation in 2014 because some remains and funerary objects were missed, he said.

The American Museum of Natural History is the largest metropolitan museum to have taken on such an initiative as early as 2002, Whiteley said

“More recently, we’ve been inventorying all of the Northwest coast remains collections to see if they can be affiliated with individual nations,” he said. “That’s been the priority.”

Cultural objects are more “complicated” because the museum has collections from across the world, Whiteley said.

The museum’s administration has agreed to “a limited repatriation” of cultural objects for the consulting curators’ nations, said Whiteley.

While Whiteley said it may be difficult for First Nations communities to appreciate, the hall has had “immeasurable influence” on social justice advancement.

“My sense is that the hall has had an immense impact on global thinking about the meaning of culture,” he said. “Particularly about Indigenous cultures of the Northwest coast of North America.”

Since 2011, Korianne Ignace has been video recording her daily life living in Usk tua, the traditional winter village of the Hesquiaht First Nation.

Many of her most prized recordings are of her late-father, Dave, whom she filmed cleaning sea cucumbers, octopus and grouse.

Because they ate octopus so rarely, Ignace said her father was the only one who knew how to clean them. As he grew older, Ignace said she made the recordings so her family knew how to clean them if he was no longer able to.

“It’s not exactly a well-known skill around here,” she said. “You have to get through the slimy part and get to [a] really big, white tendon, or the middle innards of the octopus.”

Ignace’s videos are included in the new iteration of the Northwest Coast Hall as part of the digital kiosk.

“It’s really nice to share his memory,” Ignace said.

He may be gone, she said, but he lives on through those recordings.

Ḥaa’yuups has yet to see the hall.

“I’m waiting to be wowed by the exhibit,” he said. “I don’t want my grandchildren thinking that I behaved cowardly when they go through the exhibit … I want them to be proud of where they’re from, proud of who they are, proud of the history of their family and the achievements of our people.”

Despite his frustrations, he said “I’m grateful for the opportunity – I can’t pretend that I’m not.”

The Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art has since asked Ḥaa’yuups to work with them to purchase Indigenous material for inclusion in their galleries.

“I’m going out there to educate people,” he said. “There's millions of things on the market from the various tribes in North America. Galleries are starting to collect those things [and] exhibit those things as art – as a high form of creative achievement.”

As much as Ḥaa’yuups said he thinks the material should be put back in the hands of the people who created it, “I know that's not going to happen anytime soon,” he said.

“So, you try to do the best or make the most of whatever situation you find yourself in,” he said. “That’s what I'm doing.”