She was in the Victoria-based newspapers back in the 1860s and she reappeared in modern news media in 2018 when a charitable organization heard about her story. The name Maggie Sutlej has appeared in newspapers and books since 1864, but that wasn’t her real name and it wasn’t the true story.

It all started in 1864, following the disappearance of the trading vessel Kingfisher and its crew. Stories made it back to Victoria that the crew was killed by Ahousaht people, and the boat scuttled. The government of the day sent warships to Ahousaht territory with orders to bring back the murderers to stand trial. Rather than looking for the truth about why it happened, their mission was to capture an Ahousaht chief and his warriors.

Dave Jacobson, Quamiina, a knowledge-keeper from Ahousaht, said that the story he knows is different than what was told in the books and newspaper articles, because they tell only one side, from the colonized perspective, he said.

Quamiina says he was raised to be a historian. He listened carefully as his grandmother and other relatives told him stories handed down the generations.

“I was taught to carry these histories, these stories and the way that I was taught may not be the same as [how] someone else was taught,” he shared. “Other knowledge carriers may tell the same story differently but there’s always truth in their stories – they’re just telling it another way.”

Quamiina said he felt offended when he read the 2018 Ha-Shilth-Sa story about Maggie Sutlej. At the time Khalsa Aid reached out to Ahousaht with a $200,000 donation in honor of her memory and of the Sutlej name, which is sacred to the Sikh community.

“It wasn’t told from the Ahousaht perspective,” said Quamiina.

He added that he appreciates what Khalsa Aid did for his people. He confirmed that there was a gunboat attack on an Ahousaht village and Ahousahts were killed. A small child was pulled alive from beneath her mother’s body by crewmen from the Sutlej. The little girl was given to the captain’s wife, who renamed her Maggie Sutlej.

Quamiina was willing to share what he knows about the story with Ha-Shilth-Sa after following cultural protocols. The story, he said, relates directly to the second Ha’wilth or chief of Ahousaht, and is told with his permission.

“Nobody was talking about the incident that precipitated the bombing of Ahousaht villages; they don’t know why Cap-cha (the Ahousaht chief) ordered his men to do what they did,” said Quamiina.

Fighting started by ‘abduction of native women’

The story begins in August 1864, when the trading vessel Kingfisher anchored in Matilda Inlet at the present-day village of Maaqtusiis, Ahousaht’s main settlement on Flores Island. Captain James Stevenson and his two crew members were there to trade goods for animal pelts.

Quamiina’s grandmother, Nellie Bishop, born 1891, was the great granddaughter of Chief Cap-cha. It was the older sisters of Nellie’s grandmother, born 1851, who went to see the crew of the Kingfisher. At that time Ahousaht people used Ahousaht names with no surnames.

“They must have been about 12 – 16 years old, they were just kids,” said Jacobson.

The story goes that the girls, lured by sugary treats and shiny trinkets, went to the boat where they were subsequently given alcohol.

“They took advantage of them, those girls, they were raped,” said Quamiina.

According to the book Voices from the Sound, written by Margaret Horsfield, Captain Stevenson had been convicted of selling liquor to Aboriginals the year before, in 1863, and was fined $500 in a New Westminster court.

Horsfield writes, “possibly due to alcohol-related incidents and the abduction of Native women by the traders, the Ahousahts’ anger ignited.”

According to Quamiina, girls are held in high esteem, especially the daughter of a chief. So, when Cap-cha’s daughter reported what had happened, the chief had to respond.

“He got his warriors and they went to punish them – they had to let them know there’s consequences for what they done,” said Quamiina of the attack on the Kingfisher’s crew. “They were killed and the Kingfisher was sunk.”

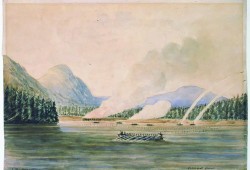

Word of the incident had gotten back to Victoria and in late September 1864, the gunboats HMS Devastation and the Sutlej were sent to Ahousaht territory to demand the surrender of Cap-cha and his warriors.

“They were looking for Cap-cha, but he didn’t feel like he did anything wrong, so he refused to surrender or give up his warriors,” said Jacobson.

Captain J.W. Pike sailed the HMS Devastation to Ahousaht territory to demand the surrender of Cap-cha and his warriors. Instead, he found the Matilda Inlet village deserted. At the Herbert Inlet village they found “a large body of Indians in their fighting paint,” wrote Horsfield.

Girl found under mother’s lifeless body

After reporting to Captain Denman, the gunboats went back to Ahousaht territory, this time with Denman at the helm of the Sutlej. They set about bombing nine Ahousaht villages and encampments over several days.

“Through all the bombing and firing, there was lots of damage and loss of life,” said Jacobson. “One was a young mother who died protecting her little daughter.”

According to Jacobson, it was the initial bombing at Maaqtusiis that caught the Ahousahts off guard. Most hid in the forest, however, there were dozens of people killed. When the crew of the Sutlej rowed ashore to what is now the front beach at Ahousaht, they found the lifeless body of a young woman lying in the sand. Her body partially covered the little girl she was shielding from the gunfire.

The toddler was pulled from beneath her mother’s body and given to Captain Denman and his wife.

“She was given the name Maggie Sutlej. I guess you could say she was a trophy,” said Quamiina.

Little Maggie Sutlej became a symbol for what those aboard the gunboats did to Ahousaht, he stated.

Quamiina knows that the gunboats went on to attack more Ahousaht villages in their search for Cap-cha and his men, but after the initial assault on Maaqtusiis, the Ahousahts were prepared and had time to hide. There were few Ahousaht casualties after the initial attack.

In the final attack at White Pine Cove on October 7, 1864, the gunboats found Cap-cha and some of his men. Cap-cha managed to escape with some buckshot in his shoulder. Some of his warriors were captured and taken to Victoria to stand trial for the murders of the Kingfisher crew.

Warriors put on trial

According to Horsfield, the navy took 11 prisoners, including Cap-cha’s wife and child. In his 2003 book ‘Living on the Edge’, late Ahousaht Tyee Ha’wilth Earl Maquinna George wrote that the chief’s child was Kitlamuxin (later to become head of the Keitlah family).

In due time the Ahousahts stood trial, accused of murdering the crew of the Kingfisher. They were eventually acquitted and released, not because they were found innocent or justified in their actions, but because they were not Christians.

Tried in the Supreme Court in Victoria, B.C., Chief Justice David Cameron acquitted them on the grounds that he could not accept evidence from non-Christians.

“These people do not believe in the existence of a Supreme Being and therefore they are not competent to take an oath,” he stated.

Ahousaht saw the battle as a victory.

“They had not given up their chief to the white man; they had lost houses, canoes and iktas (things), but these they could and would build again; some of their number were taken prisoner, but were afterwards returned to them…therefore they claimed a big victory over the man-of-war and big guns,” wrote Father Augustin Brabant in his memoirs, a 19th century missionary who served for many years in Hesquiaht.

Did Maggie Sutlej really die at sea?

Just over 100 years later in 1967, John Jacobson, an Ahousaht historian, Second World War veteran and artist took part in a celebration recognizing Canada’s 100th anniversary. According to Quamiina, his uncle John Jacobson, or Kamiina as he preferred to be called, presented carved totem poles to George Pearkes, the lieutenant governor of British Columbia. He was joined by other Ahousaht elders, one being David Frank Senior.

“At the same time he gave them cannon balls or unexploded shots from the Sutlej from when they had bombarded Muuyahi where Ahousaht had a encampment,” said Quamiina. “Giving back the cannon balls was a way of saying we are here even after Canada showed aggression against Ahousaht.”

So, who was Maggie Sutlej? If Ahousaht historians knew her real name, they haven’t shared it. But they know she came from the Charlie family of Ahousaht. According to Quamiina, the late John Charlie’s grandmother would have been a sister to Maggie.

David Frank II also knows the history and said Maggie came from the Charlie/Hunter/Frank families. The present-day Franks of Ahousaht changed their surnames from Hunter. “John Charlie used to tell us we should change our names back to Hunter,” said Dave Frank, Ahousaht historian. “She (Maggie) came from Kelsmaht,” said Frank.

Kelsmaht is located on Vargas Island, across from Tofino. They amalgamated with Ahousaht in the 1950s.

Quamiina knows that his own grandmother, Nellie Bishop, descended from an aunt of Maggie Sutlej.

According to the history books, Maggie was dressed in the finest clothes and spoilt by all around her. They say she died less than two years after her abduction, or adoption as the history books call it. The story is Maggie died aboard the Sutlej as it sailed off South America and she was buried at sea. Her name is inscribed on a memorial marker along with other Sutlej sailors who died at sea. The marker is in an old cemetery in downtown Victoria on Quadra Street.

But Ahousaht historians know that there is much more to the story than what has been documented.

“You just have to look at her picture and you can see a sad girl,” said Quamiina. “We believe that because she was so unhappy, she was put ashore in Washington State.”

According to Frank, Maggie Sutlej managed to escape the boat while it was in Washington State. He doesn’t know where the boat had landed or how Maggie escaped. She eventually learned the local language, married and had children. She taught her children both languages she knew.

Several decades later people from Ahousaht went to work in the Fraser Valley picking hops. As they worked, they spoke their Ahousaht language to one another. According to Frank, they were approached by people from Washington state who told them that they used to hear their mother and grandmother speak that same language. “She said she was a Hunter,” they told the Ahousahts.

David Frank Sr, 1901 – 1985, was Dave Frank’s father. David Sr. had an uncle named Charlie. “They (American relatives) really wanted him (Charlie) to move down to the states – they had an orchard there in recognition of their mother and grandmother,” said Frank. It seemed they wanted a connection with their grandmother’s family to live nearby but Charlie never did move.

“My father used to get Christmas gifts every year from the family,” said Frank, adding that he would love to go down there and find them, but he doesn’t know where to look.

“I imagine they go by the Hunter name,” said Frank. In recent years, Frank’s nephew accompanied relatives taking part in Canoe Journeys, hosted by a Washington State tribe. He was in his boat which had the name Frank-Hunter painted on the cabin. “The people came and asked them about the name and said they were family,” said Frank.

“It would be good to find them and connect with them,” said Frank.

“There’s family there, that exists today. They come from Maggie,” said Quamiina.