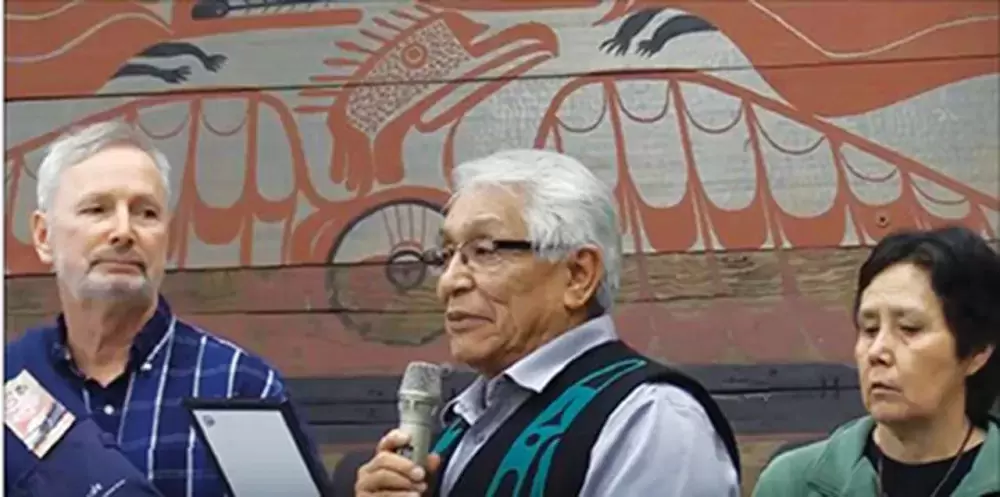

Huu-ay-aht Chief Councillor Robert Dennis held up a framed piece of paper. It was a copy of a land transfer document, found when Huu-ay-aht First Nation was looking for the nation’s artifacts at the Royal British Columbia Museum. The intent was to repatriate those treasures back to the nation.

The original transfer document was from 1859, something the Huu-ay-aht chiefs back then had insisted that government agent Eddy Banfield sign before acquiring land in Huu-ay-aht territory for a trading store.

The chiefs also insisted that each of their names on the document be marked with a seal of cedar bark as part of their sacred connection to their territory.

On Nov. 19, 2016, when Huu-ay-aht did receive their treasures back, cedar bark was added to the official document that transferred their possessions from the museum.

The CEO of the Royal B.C. Museum, Prof. Jack Lohman, was pleased.

When you look in the archives, he said, many of the very early first nations documents, colonial documents signed by first nations, are sealed with pieces of cedar, “so, in a way, it makes these kinds of documentations pretty unique.

“When you look at them it looks like they were written by Charles Dickens, but at the end they have something like plants stuck on them. They are very unusual. They are so unusual I suggested to UNESCO, the United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization—the UN cultural organization—to add these to the memory of the world, to the most important documents in the world,” said Lohman.

The suggestion has gone to a nomination process, and it then it goes to the United Nations in Paris.

“They are so unusual,” he said. Other treaty documents between Indigenous people and colonizers, for example in New Zealand, they don’t have this sealing, Lohman explained.

“The cedar bark is something very, very particular to this geographic location, so it’s lovely to be able to go back to the history, in a way to reconnect with that history, and understand what makes this particular area unique. Because, in a way, those seals are voices. They carry the voices of Indigenous people. We must never forget that.”

He noted that these are colonial documents and very often viewed as land transactions.

“The colonizers had a different perception about land, and a connection to nature. And actually we’re now relearning, if you like, an understanding of the importance of Indigenous knowledge, that there are other ways of looking at nature, looking at land and people’s association, attachment to the land.

“Land and people are one in Indigenous terms as I understand. They are not transactional pieces.”