First Nations are stepping up pressure, urging the federal government to get back to the table as soon as possible and conclude talks involving a marine protected area four times the size of Vancouver Island.

Government-to-government negotiations on the proposed Tang.ɢwan-ḥačxʷiqak-Tsig̱is Marine Protected Area (MPA), also known as the Pacific Offshore Area of Interest (AOI), were sidelined during the 2021 federal election campaign.

Leaders of the Council of the Haida Nation, Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, Pacheedaht First Nation and Quatsino First Nation wrote last week to Fisheries Minister Joyce Murray, asking her to re-engage DFO in order to reach a memorandum of understanding within weeks.

“We call upon you as the new minister to step forward and deliver on promises to work together in the spirit of reconciliation by directing the responsible decision-makers in your department to meet with our leadership with the objective of resolving the outstanding areas of disagreement by the end of January 2022,” they wrote.

MPAs are large coastal and offshore zones where certain activities such as bottom trawling, oil and gas exploration and seabed mining are restricted to reduce human impacts on ecosystems and biodiversity. In July, former Fisheries Minister Bernadette Jordan said the government would allocate $977 million in its current budget to continue marine conservation efforts with a goal to protect 25 per cent of Canada’s oceans by 2025 and 30 percent by 2030.

“Our Earth is in danger,” Governor General Mary Simon read from November’s Throne Speech in Parliament. “From a warming Arctic to the increasing devastation of natural disasters, our land and our people need help. We must move talk into action and adapt where we must. We cannot afford to wait.”

The Liberal government also promised to address biodiversity loss with greater protections: “In this work, the government will continue to strengthen its partnership with First Nations, Inuit and Métis, to protect nature and respect their traditional knowledge.”

First Nations consider marine protected areas not only as a route to co-governance but as a vehicle for re-establishing decision-making autonomy and rebuilding marine resources.

In the run-up to the federal election, the Liberal government was prepared to proceed with official designation of the new MPA.

“They told us the Offshore Pacific Area of Interest was close to being complete,” said NTC President Judith Sayers. “We told them, no, that’s not going to happen. We have outstanding issues that need to be resolved.”

Along with co-governance, First Nations want the MPA management board’s scope of responsibilities to include decision-making authority in fishery matters and a dispute resolution mechanism.

After a flurry of discussions, the federal government agreed to resume talks after the September election. Sayers said.

Murray, MP for Vancouver Quadra, likes to recall her years planting trees and running a reforestation company in the B.C. woods. She wrote a master’s thesis on global warming before entering provincial politics in the 1990s.

“I’ve known her for a lot of years and she is from the West Coast, so we really hope she will pay attention to this,” Sayers said.

Pressure has been mounting on the federal government to follow through on marine protected areas, to not only increase MPAs but to improve existing ones. According to recent analysis from the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS), the protections provided by Canada’s MPAs don’t live up to their promise. Using a guide developed by the Seattle-based Marine Institute to assess MPAs, they analyzed 17 in Canada and found 60 percent do not have strong enough protections in place to protect biodiversity.

“That’s the piece that’s eye-opening,” said Kate MacMillan, CPAWS ocean conservation manager on the West Coast. “Hopefully, not only government but also the general public will sit up and take notice.”

Marine ecosystems face multiple threats, yet MPAs remain one of the most effective tools to restore ocean habitats, rebuild biodiversity and help species adapt to climate change, the report states. Along with climate change, McMillan lists biodiversity loss, ocean warming, acidification, deoxygenation, rising sea levels, increased sedimentation and heat domes, such as those last summer that claimed an estimated one billion intertidal sea creatures. MPAs can help with these environmental stressors by creating areas where human impacts are reduced, she said.

“With all of the pressures on marine life, hopefully these MPAs will remove some of those stressors,” she said. “Anything we can do is important to highlight.”

If the federal government were to enact minimum standards for existing MPAs as recommended, two of the Pacific areas would move up the scale and provide greater assurance MPAs are doing as intended, MacMillan said.

“We would see a big benefit,” she said.

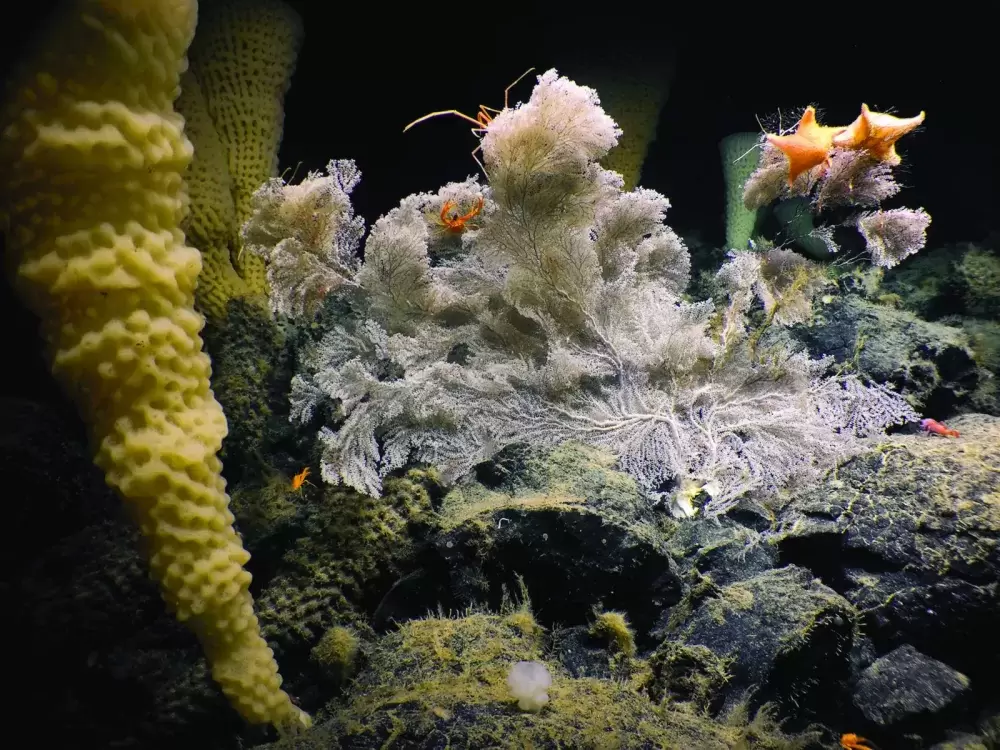

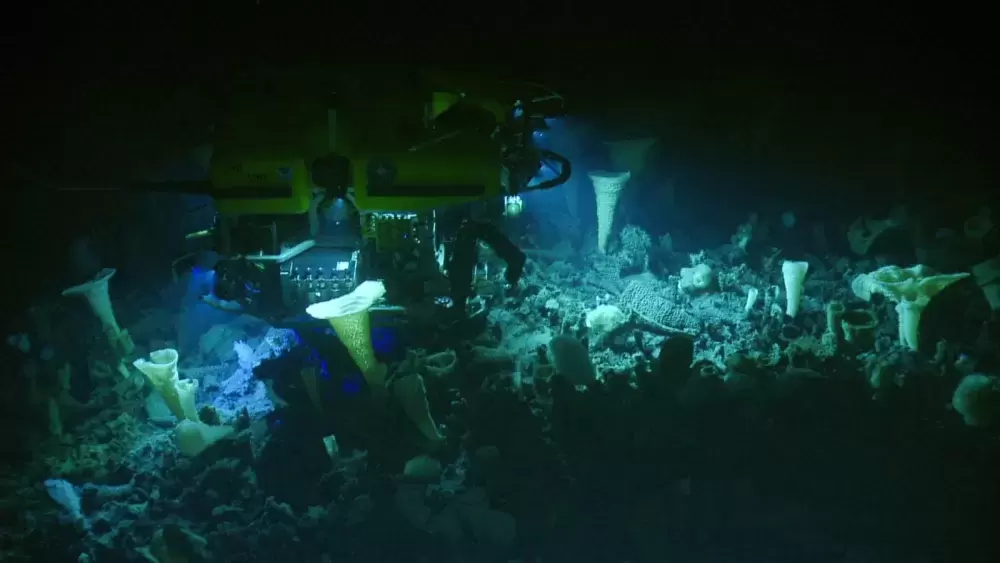

As proposed, Tang.ɢwan-ḥačxʷiqak-Tsig̱is Marine Protected Area spans B.C.’s south coast, an area of 133,000 square kilometres, extending roughly parallel to the Strait of Juan de Fuca in the south and Bella Coola in the north. It would incorporate seamounts as high as Mt. Baker and the Endeavour hydrothermal vents, Canada’s first marine protected area established 20 years ago.

“These things are worth protecting,” Sayers said, addressing the environmental side of the equation. “This is our territory. These are our territorial waters. We need to do what we can to protect and preserve them. This is one tool, but it’s not the only tool.”

Along the same lines, there was a motion on the floor at the AFN’s Special Chiefs Assembly held this week to consider putting Indigenous MPAs in place, she noted.

Murray has yet to respond to the Dec. 1 letter from First Nations, but she expressed firm support for MPAs in an online “fireside chat” hosted by CPAWS Wednesday. Five weeks into the job, Murray said she is still focused on opportunities, not challenges.

“I think the opportunity with marine protected areas is enormous,” Murray said. “It’s an opportunity to advance our reconciliation, intentions and commitments. It’s an opportunity to work collaboratively, even more deeply, with communities and environmental organizations …”

“The challenges are those that are always inherent in having big ambition,” she added. “I’m optimistic. People excited about the outcome learn to work together to work out the kinks along the way.”