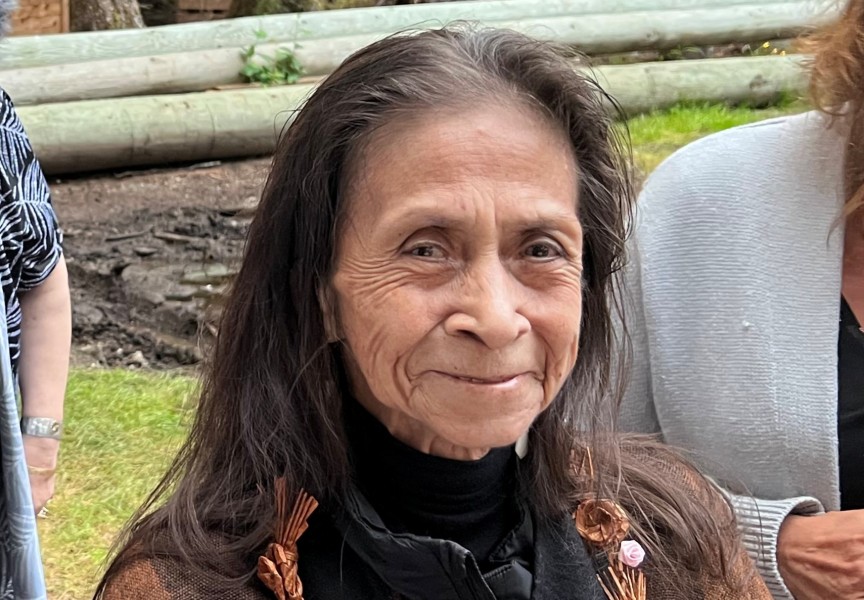

Nuu-chah-nulth women in Port Alberni are among those who are being mailed at-home cervical screening kits as part of a pilot project.

BC Cancer officials started mailing out kits this past December. During the pilot project, which will run for approximately 12 months, about 67,000 kits will be mailed to women in central Vancouver Island as well as the Sunshine Coast on the province’s mainland.

The easy-to-use kits will have everything women require to self-screen for the high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV). After collecting a sample, participants in the pilot project will simply mail it back.

Officials will send kits to women included in the database for the BC Cancer Cervix Screening Program.

Only those who are invited to participate in the pilot project can do so. Individuals cannot request that their names be added to the list of invitees.

Dr. Gina Ogilvie, an affiliate scientist with BC Cancer and one of Canada’s leading experts on HPV, said she is uncertain how many Nuu-chah-nulth or Indigenous women have already received kits or how many will be included in the pilot project.

Since labelling kits and then mailing them out are time-consuming processes, Ogilvie said kits will be mailed out in various phases throughout the year.

“We don’t want to flood the labs with all the tests at once,” Ogilvie said.

Besides Port Alberni, other communities in central Vancouver Island that are being targeted in the pilot project are Parksville, Qualicum Beach, Lighthouse Country, Coombs, Errington and Nanoose Bay.

Meanwhile, some women from the following Sunshine Coast communities will also be mailed kits: Earl’s Cove, Langdale, Madeira Park, Pender Harbour, Sechelt, Robert’s Creek and Gibsons.

Ogilvie said Indigenous women have a greater tendency to not visit health centres in order to be screened for cervical cancer.

“There’s a lot of reasons why historically they would be under-screened,” she said.

Ogilvie said many Indigenous women live in isolated and remote communities. Many would have to overcome travel and other obstacles just to get to a health centre.

Ogilvie believes past discrimination could also potentially be one of the reasons some Indigenous women do not get tested.

“Maybe there is legitimate reticence about going to a health centre because of the discrimination they’ve faced in the past,” she said.

This pilot project eliminates the need to travel to a health centre for testing. And it can be done in the convenience of one’s home.

Participants are encouraged to do the test shortly after it arrives and mail it back in short order. “The kits are very stable for several weeks,” Ogilvie said. “We’re hoping people use the kit and send it back to us as soon as possible.”

There is a greater urgency to catch cancer early on among Indigenous women. The BC Cancer Agency had co-authored a study with the First Nations Healthy Authority in 2017.

That study was published in the journal Cancer Causes & Control. The study showed a 92 per cent high incidence rate of cervical cancer observed among First Nations women when compared to non-Indigenous women.

It should be noted, however, that data for that report, which was collected between 1993 to 2010, included only ‘Status Indian’ people and not all First Nations, Métis or Inuit women in B.C.

Ogilvie has been involved with other cervical screening projects within the province in previous years.

“Women by and large love it,” she said, adding they don’t have to arrange childcare to go to an appointment or be hindered by time or travel costs getting to a health facility.

Ogilvie is hoping funding and the means will be available for all eligible women in the province to be mailed screening kits to their homes.

“Ultimately that’s what we want to do,” she said.

Funding for the pilot project was provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer.

Ogilvie is also hoping one day cervical cancer will become a thing of the past.

“We have everything we can to prevent this cancer,” she said. “We have a vaccine and we have screening.”

The World Health Organization is among those who have put out a call to eliminate cervical cancer. Ogilvie believes this can be achieved by 2040.

It is believed that about 190 women in British Columbia were diagnosed with cervical cancer in 2021, a number that Ogilvie said has been pretty steady in recent years.

Warren Clarmont, the provincial director of Indigenous Cancer Control with BC Cancer, speaks highly of the pilot project.

“This pilot opens the door to the potential of at-home screening, which will help reduce barriers to access for Indigenous people, particularly those residing in more rural and remote areas,"” Clarmont said. “We are hopeful that by bringing screening closer to home, this pilot will help to increase cervical screening participation amongst First Nations and Métis peoples.”

Adrian Dix, the Minister of Health, is among those preaching that cervical cancer is preventable.

“Cancer impacts many lives, and we are working to make sure services are in place to help prevent this disease,” Dix said. “With at-home screening, people in need of cervix screening will face fewer barriers which may include cultural issues, trauma, inconvenient clinic hours, transportation concerns, and the need for time off work or child care.”

Dr. Dirk van Niekerk, the medical director of cervix screening for BC Cancer, also said cervical cancer can be avoided via regular screening.

“Cervical cancer is almost entirely preventable and regular screening is one of the key ways you can prevent it,” van Niekerk said. “That is why it is important for BC Cancer to continue to find new, innovative ways to reduce screening barriers for our patients. This pilot will help us fine-tune our patient communications, provider engagement and internal processes to better serve our patients.”