Nuu-chah-nulth people have been traditionally known to hunt whales migrating along the west coast of Vancouver Island for what Tommy Happynook (Hiininaasim) of Huu-ay-aht said could be thousands of years.

For Happynook, he comes from a family of whalers who hold the title of head whaling family for Huu-ay-aht. He recalls the last member of his family to hunt a whale was his great-grandfather, Bill Happynook, in the 1920s.

Happynook said that, from his understanding, Nuu-chah-nulth collectively stopped whaling due to declining populations of the animals.

Though whales have not been hunted since, Happynook said that for his family the responsibilities of being whalers remain.

“Whaling still plays a really important part within my family,” said Happynook. “The teachings that we would have aspired to live by every day continue.”

“I try to live by those principles,” he added.

As whalers, his family held a responsibility to provide a substantial resource to the community.

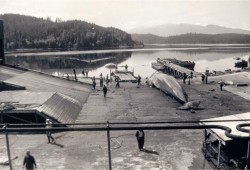

“That meant the meat from the whale, the blubber, which could be rendered and turned into oil or eaten, [and] the many tools and arts that could be created from the whale bone,” said Happynook.

Each family within the community was assigned a piece from the whale so they knew they would receive a portion when it arrived, shared Happynook. Those who assisted with the hunt would have gotten particular pieces to honor their role, such as the head whaler and harpooner, who may have received the saddle, he added.

Harpoons, lances and sealskin floats

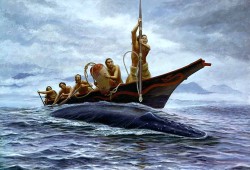

According to Phillip Drucker’s the book The Northern and Central Nootkan Tribes, when a whale was spotted, the canoe moved “noiselessly” in the direction of the animal, with the harpooner at the bow of the vessel, ready to strike.

“The harpooner stood with his right foot on the forward thwart, his left on the gunwale close to the prow piece,” it reads. “He held the harpoon ready, his right hand palm down, his left farther up the shaft, palm upward.”

“The success of the harpooner depended to a great extent on the skill of his crew, particularly that of his steersman,” continued the book, which was published in 1951.

“Picking the right time to do that was absolutely critical,” said Kevin Neary, who has been a researcher directed by Mowachaht/Muchalaht, gaining his knowledge of whaling through research and interviews with Nuu-chah-nulth elders. “The steersman in the back would wait until the whale's tail was close to the surface in the water coming on the upswing and then he would say, ‘Now's the time to strike’.”

The harpoon, as Neary describes, would twist and fasten into the whale, like a barbed hook.

The purpose of the harpoon was to strike the whale, connecting it to sealskin floats to slow the whale down, and afterward keep the whale floating once it was dead, shared Happynook.

Neary said that if the opportunity was presented, the harpoon would be used to strike the whale multiple times to add more floats.

Happynook said that a lance, a long sharp tool, would be used to kill the whale, puncturing the lung.

“The idea behind it is that if the whale can't take a deep breath, it won't be able to dive as deep or pull the canoes out as far,” said Happynook.

Other techniques used to kill the whale include using a special lance that cuts the tendons controlling the fluke of the whale, and then using another lance to pierce underneath the flipper, according to Philip Drucker’s book.

One of the crew members would jump into the water once the whale was killed, sewing up the mouth and blow hole to ensure that the whale stayed afloat and did not sink, said Happynook.

He added that there would be a minimum of four to five canoes helping in the hunt as scouts, supporters, and a canoe to return home to announce the kill to the community so that they could prepare.

“There may have been someone who was leading the hunt, but multiple families would have been participating as well,” said Happynook.

The practice of whale hunting was extremely well designed, said Neary.

“It was meshed absolutely perfectly with the behavior of the whales,” he shared.

A valued resource that brought wealth

If the hunt brought their crew into another nation’s territory, this was something that they would be mindful of, explained Happynook.

“If a whale took us into another nation’s territory, there was obligations to go to them and share or give an offering… before being able to take the whale back to your community,” said Happynook.

In some archeological records whale bones associated with Nuu-chah-nulth have been found in northern and north central British Columbia, shared Happynook. Neary added that trades extended down the Columbia River, into Washington and beyond.

“Nuu-chah-nulth people were quite wealthy,” said Happynook, noting that their wealth was due to providing a resource that certain other tribes couldn’t obtain.

“It not only had economic significance, but also incredible cultural and spiritual significance,” said Neary. “It was considered the apex practice for any individual or group of individuals to be engaged in whaling.”

“You spent a great deal of time preparing to hunt a whale,” said Happynook, adding that it likely took most of the year to focus on spiritual, mental and physical preparations, including ritual and ceremony.

Preparations varied from whaler to whaler. Rituals, ceremonies, equipment and tools used to prepare for the hunt would depend on the watershed each whaling family was from and the resources from that area, explained Happynook.

As a whaler, hunting a whale required extensive preparations ranging from physical training, isolation from family, fasting and bathing, tending to the hahoulthee, among other practices.

“It really was a celebration, right, there was a recognition that the whale had some autonomy in allowing us to harvest it,” said Happynook. “Through the various rituals and ceremonies, you were trying to connect to a whale who was willing to give its life so that you could feed your community.”

A shrine for whalers

Yuquot, located on Nootka Island and home community to the Mowachaht/Muchahlaht, is also well known for the Whaler’s Washing House.

“It was like a shrine where the whalers would go to pray and to sing and to prepare themselves physically, and mentally, and spiritually,” said Neary.

In the early 1900s the shrine was collected by the American Museum of Natural History, and continues to reside in New York.

“[It] is considered to be one of the most sacred collections of Indigenous material,” said Neary.

For each Nuu-chah-nulth nation, whaling is likely to take variations, said Happynook.

“I think it really depended on access to the outer coast,” said Happynook. “For nations who were right out on the outer coast, whaling, I think, could be an easier expedition than for nations who were maybe further down the coast and had to adapt different techniques and ways of practicing whaling.”

Happynook shared that although his family has been displaced from their hahoulthee, čaačaaciias, now known as Carnation Creek Watershed, he has been working towards rebuilding the connections and relationships with that area. This is so that if one day Huu-ay-aht decides to whale again, the Happynook family can participate.