Like a scene from an Indiana Jones movie, Toquaht citizen Dennis Hetu couldn’t believe his eyes the day he stumbled upon an ancient clam garden in his ḥaḥuułi (traditional territory) on the west coast of Vancouver Island.

The action unfolded over 20 years ago, but Hetu remembers it like it was yesterday.

Having just acquired a commercial licence to harvest oysters, Hetu was out on the water scouting beaches when he came across an inviting spot for clamming. It was low tide, he had a rake on hand, plus his aunt had requested clams for dinner…so he boarded the beach and started digging.

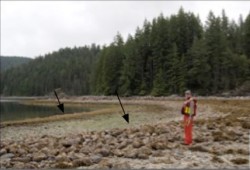

“I was very weary of the beach because I knew that bears were around. My head was on a swivel. I thought I heard something, so I looked up and that’s when I saw the first arch,” Hetu recalls.

Arches are rock walls created by Indigenous ancestors by rolling boulders down to the lower intertidal zone to increase access and clam productivity. According to the Clam Garden Network, gardens produce at a rate of 150 to 300 per cent more clams that grow quadruple the biomass than non-modified spawning grounds.

“I have lots of experience as an archeologist, so I knew right away what I was looking at,” Hetu said excitedly. “This is a clam garden. What I didn’t realize was that it was a farm, until I found the second row. And then another one.”

Much to his astonishment, Hetu had discovered not one, but four arches on these ancestral grounds.

“I had just finished doing all these courses for shellfish aquaculture. It all clicked to me. That’s a four-year cycle for a clam. Each arch was harvested each year, so by the time they got to the top arch, the first arch was ready to be harvested again.”

With four arches in plain sight, Hetu’s find represents an ancient system of mariculture and the first real evidence of sustained shellfish farming in Toquaht.

“This is a piece of history; history that had nothing to do with profit. It was just all about food. It was about keeping a community fed in times that were really tough, like winter. Back then there were no roads. There was nothing other than water access,” said Hetu.

If the system was working efficiently, Hetu says his ancestors could yield about 6,000 pounds of clams out of each arch. These rock arrangements helped with the husbandry of clam spawning by helping disperse the reproductive process – after harvesting all the edible clams in the first arch, the next arch would spawn that very same year.

“That could easily feed 100 people over a month,” he said, noting that a biomass study was conducted to determine the estimate.

Due to the location of the ancestral clam farm, Hetu believes it was the job of one family to maintain the site daily and to harvest the clams for their people.

“Whichever family was utilizing that site was very successful in feeding their people. It’s the only site I’ve seen utilize that method. It’s super smart is what it is,” he beams.

Historically, coastal First Nations would eat four types of bivalves: butter clams, littleneck clams, cockles and horse clams, according to the Clam Garden Network.

Today, it’s the Manila clam, a species Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) says was accidentally introduced in Canadian waters during the 1930s in oyster seed from Japan, that are the main commercial clam found in abundance in the intertidal zone of B.C. Manilas, like the native littleneck clam, are steamer clams that separate easily from the shell after cooking.

Hetu says his ancestors used cedar bark baskets to haul the clams back to the village, but he’s not quite sure what they used to dig them up.

“I’m wondering if they used a stick that they steamed and bent into the shape of a rake. Hands would be doable, but hard. I think they would have used a tool.”

The clams were eaten fresh, steamed or smoked and dried for later consumption.

“They ate clams for sustenance. Today it’s a treat, but back then it was a necessity,” said Hetu, who enjoys eating clams sauteed in garlic butter with a little salt.

Nowadays, butter clams are a real treat for elders.

“They’ll open it up, put it in a patty and make clam fritters or clam cakes,” Hetu shares.

The refuse from meals would go to a communal site known as middens, where people brought all their shells, bird bones, fish bones, bear bones and even eggshells. In the middle of Toquaht’s main village of Macoah, Hetu says the nation excavated a “very large” midden site that was 12-feet deep by 30-feet in diameter.

“They had little small middens in front of each house or settlement, but as a community there was one site that they brought all the bones to lessen chance of wildlife entering the property.”

While Hetu guesstimates his ancient clam farm is over 300 years old, a 2019 study funded by the Hakai Institute found clam garden sites on northern Quadra Island in the traditional territories of the Laich-Kwil-Tach and northern Coast Salish peoples to be over 3,500 years old.

The researchers conducted subsurface testing, sample collection and radiocarbon for dating nine clam garden sites, six in Kanish Bay and three in Waiatt Bay.

“These rock-walled intertidal terraces, in combination with a variety of cultivation techniques, enhanced clam productivity and abundance through a variety of mechanisms,” the study notes. “In the past, as today, these features were linked to the governance, livelihoods, and identity of coastal First Nations from Alaska to Washington State.”

Hetu has since returned to his ancient clam farm only to find it in ruins, the rock walls toppled by bears and humans. Although historical protection protocol with the government fell through, Hetu maintains the uniqueness of the site.

“I’ve been to a dozen garden sites up and down the coast and the only one that I’ve ever found with four arches is right here. That’s why I’m sure that it was the first type of farming because all the other sites have one big arch.”

Hetu’s face lights up when he talks about digging clams for his family. He says this story of archeological discovery is important to tell and offers teachings for the next generation.

“Every time I step out on the land now, I know that every inch of it my people have walked on. I can’t walk anywhere without thinking that first and being grateful.”

With guidance from Hetu and cultural leaders, the Nuu-chah-nulth Youth Warrior Family will restore Toquaht’s historic clam farm this November.

This story was made possible in part by an award from the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

This is article is part of a series of stories on Nuu-chah-nulth clam gardens. The next article will look at how the Warriors rebuild the clam garden and following that, we will lean into the issue of food sovereignty.