The proponents of the Raven Underground Coal Project have failed to address the issue of aboriginal rights and title, according to Tseshaht First Nation.

On May 16, the provincial Environmental Assessment Office (EAO) informed Compliance Coal Corporation CEO John Tapics that his application for an environmental assessment certificate failed to meet the requirements to move to the detailed review stage.

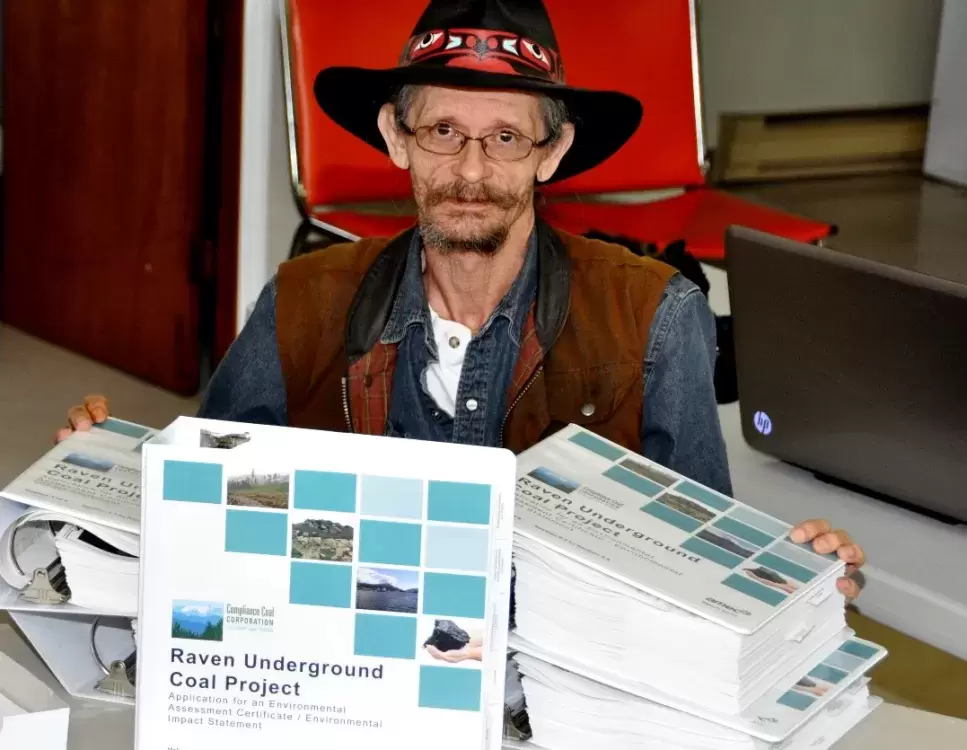

Keith Hunter serves on the Tseshaht technical team that worked with the Intergovernmental Working Group, which includes EAO and the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency (CEAA).

“During the first public review process, a couple of years ago, what they were doing was identifying issues to determine the Application Information Requirements,” he explained.

Based on the requirements that had been identified (387 pages), Compliance Coal created an application package that weighed in at more than 12,000 pages, but failed to adequately address numerous critical areas such as effects on water quality at the mine site and in Port Alberni harbour, as well as the undertaking of meaningful consultation with First Nations.

For Tseshaht, it would be difficult to pinpoint which deficiencies are the most troubling. On a purely technical basis, Hunter said Tseshaht has serious concerns about the potential effects of dredging in the harbour to accommodate the Panamax-class ships that would haul Raven Coal’s products to China. The team requested sediment test data from Compliance Coal.

It has long been understood that the “fibre mat” on the bottom of the harbour, formed over the decades by kraft mill effluent, contains a host of toxic residues such as dioxins and furans. Releasing those toxins by dredging could have disastrous effects on the Somass River Estuary, which is a critical link in the Pacific Flyway migratory corridor, and B.C.’s fourth-largest salmon-producing river.

Hunter said Compliance Coal originally proposed dredging and landfilling the sediments without any testing.

“We said we are not going to go along with you digging up toxic sediments, putting them in a truck, hauling them through the reserve and dumping them at the landfill without any testing. What is in those sediments?”

Hunter said Compliance Coal did the testing, but delayed providing the results until 12 hours before a scheduled Working Group meeting, making it difficult to conduct a meaningful review in time for discussions. They subsequently failed to advise Tseshaht of a later, more detailed study that had been ordered by EAO.

Likewise, the company failed to advise Tseshaht of a geotechnical report that indicates the extensive pile driving necessary to build a Panamax berth could destabilize the existing port facilities and even the adjacent hillside.

“If we would have had the information about the additional [sediment] testing, and about the geotechnical testing during the consultation phase, that would have changed the questions we would have been asking,” said Hunter.

“Because we didn’t feel we had disclosure of the information we needed for meaningful discussion during the consultation period.”

Those are a few of the troublesome technical points where “failure to consult” came in. Others proved to be “offensive,” according to Hunter. None more so than Section 22.13.7.13.2, Healthy Living:

“Positive effects are likely to occur for all persons with increased income as a result of employment and income at the proposed Raven Project. Based on evidence presented by Shandro et al (2012), negative residual effects may occur for some sensitive individuals in Aboriginal communities who have low coping skills and / or do not take advantage of opportunities provided to develop coping skills. Such effects are likely observable on the individual but not on the community level.”

“That’s just one example,” Hunter said.

Compliance Coal also included an assessment of Tseshaht and Hupacasath First Nations, covering history, social structure, governance, religion, etc.

“I was reading this section and I said, ‘Where did this come from? It didn’t come from Tseshaht, and I’m pretty sure it didn’t come from Hupacasath.’ I kept reading, and found out their source was WikiBooks. That’s where they got their aboriginal background.”

Hunter said he feels cutting-and-pasting from an unverified source such as WikiBooks is “offensive,” and accepting it without comment could conceivably enshrine erroneous information about Tseshaht and Hupacasath First Nations on the public record.

In a media release issued May 21, Compliance vice-president Stephen Ellis accepted the EAO’s rejection of the application and advised his company would re-group and re-submit following a new round of study.

“As we have maintained all along, a comprehensive study delivers a high-quality environmental assessment, incorporating extensive public and aboriginal consultation – this screening review is simply the first round,” Ellis said.

Ellis added that receiving screening comments is “typical and not unexpected after a first review. They include references to most of the environmental categories, Public and First Nation consultation.”

Hunter said if the company decides to move forward it will have to change its approach to consultation to include listening. On one occasion, the company held a meeting with Tseshaht to discuss the economic benefits of the project, but the event proved to be a one-sided presentation by Compliance officials, he said.

“A PowerPoint presentation is not consulting,” Hunter said.

What stakeholders had to keep in mind, however, Ellis reminded, was that the review of the application process was to determine whether Compliance had met the objective of including all of the Application Information Requirements, not whether they had been addressed and resolved to everybody’s satisfaction.

“That was one of the challenges we faced,” Hunter said. “Is this an application deficiency or do we not like the project?”

Port Alberni city manager Ken Watson, who prepared a report for council, said he also had to keep those ground rules in mind.

“We advised the working group that the company addressed the issues identified, but that the city would have further comment on whether they had been addressed substantively,” Watson said. “I went through the parts of it that impacted on the City of Port Alberni, which is a lot less than 12,000 pages. The parts on the transportation of coal, the impact on city streets, noise, etc.”

Watson said the city does not have the resources or the expertise to perform a detailed review in areas such as environmental impacts on wildlife. That would have involved hiring outside consultants at high cost, he said. What was accomplished was done in-house.

Hunter said dealing with costs is also difficult for First Nations. The Tseshaht technical team includes fisheries biologists Andy Olsen and Bob Bocking, with some help from Tseshaht chief operating officer Cindy Stern, who is a forester by profession.

Hunter’s own resume includes decades of fieldwork in the oil industry, so site development proposals (from the proponent’s side) are a familiar exercise. That gives him some perspective on the stresses facing Compliance and how they may have taken shortcuts in preparing their application. But the process has been onerous on Tseshaht, and does not look to be over any time soon.

“The problem with these projects is you don’t have any idea how much they are going to cost,” he said.

Hunter said he spent most of a month reviewing the application package. The EAO imposed two one-week extensions on the 30-day review process in order to complete the process.