The statistics are grim: in B.C. there were 999 street drug overdose deaths involving fentanyl between Jan. 1 and Oct 31, 2017. That’s a 136 per cent increase over the same time period in 2016. Fentanyl was involved in 83 per cent of all street drug deaths in that time period.

The Nuu-chah-nulth community has not been spared from the devastating effects of the fentanyl/opiod crisis. After a mind-numbing string of overdose deaths, Nuu-chah-nulth nations have launched a series of hands-on training workshops to teach community members in the use of the opiod antidote Naloxone.

On Dec. 8, Hupacasath First Nation held a workshop organized in part by youth and elder coordinator Caroline Tatoosh.

Twenty-five people took part, ranging in age from 55 years old to as young as 13. Tatoosh picked up the youth participants at ADSS and transported them to the Hupacasath Youth Centre.

"[RCMP Aboriginal Policing Officer] Constable Macleod did a video on harm reduction, showing the effect it [opiod use] has on a person," she said.

The big lesson was that there is no single description of a "drug addict," Tatoosh said. It's not just the street person – the current opiod crisis cuts across all ages and all walks of life.

"It can affect persons who have done well in their lives, and then have a bad road that they travel,” she said. “That's what we wanted to express to the kids – that it can be anybody. And we want them to be prepared."

Tatoosh said the youth participants initially thought they didn't need the training, because they didn't hang out with drug users. By the end of the presentation, they were fully engaged and wanted more.

"They realized, 'I can help somebody,'" Tatoosh said, adding that her own daughter took part, and now has ready access to one of the Naloxone kits being distributed in the community.

"One thing we talked about was making this a yearly thing," Tatoosh said. That would allow participants to debrief on any encounters they may have experienced, and to pick up any new knowledge or procedures.

On Dec. 21, Ha-Shilth-Sa attended a Naloxone workshop in the Tseshaht boardroom, conducted by Gail Gus and Community Health nurse Francine Gascoyne. All told, six adults attended.

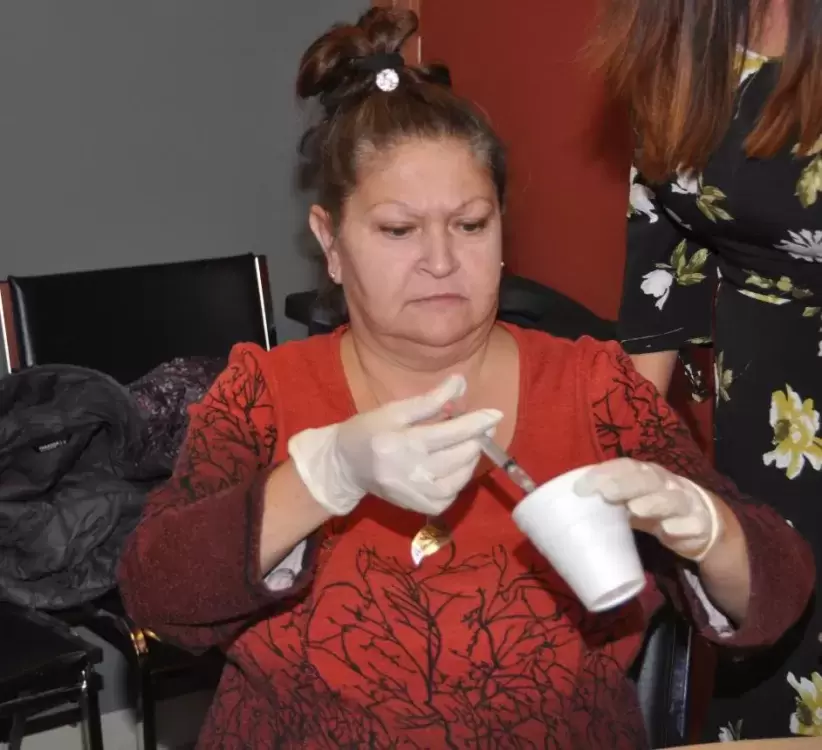

Holding up one of the Naloxone kits, which are slightly larger than an eyeglass container, Gus said the package includes three vials of the antidote, a syringe, rubber gloves and a face shield for performing mouth-to-mouth without risk of accidental drug contact.

“The more kits we get out there, the better,” she said in her introduction.

“The latest news is, kits are available through pharmacies,” Gascoyne noted. “And this just came out yesterday: fentanyl (detection) strips are going to be available at overdose prevention sites as of the end of this month.”

By using the strips, under supervision, the user is able to detect the presence of fentanyl in their drug. The strips don’t indicate how strong the drug is, Gascoyne added, “but it does give them a warning.”

Gus noted that a number of Tseshaht members have been saved through Naloxone.

Const. Scott Macleod, the RCMP’s aboriginal policing officer, then presented a 12-minute video titled, Naloxone Saves Lives. Narrated by drug experts and recovering drug users, the video warns that for drug users, the rules have changed. That “person crashed out on the couch” may be in the initial stages of a potentially fatal drug overdose.

As noted, fentanyl is now being found not only in heroin, but also in non-opiod drugs like cocaine or crystal methamphetamine. Part of the problem is drug traffickers often use the same scales and equipment to parcel out a variety of drugs.

“And you need about two grains of fentanyl to overdose,” Macleod said. Even worse for carfentanyl, he added. “That stuff is used to tranquilize rhinos and elephants.”

Macleod later recounted the story of three well-off men attending a wedding at a country club in Abbotsford who slipped into the washroom to consume what they thought was cocaine. The coke was contaminated with fentanyl, and all three quietly collapsed on the floor. Had another guest not intervened, that B.C. fatality total would have reached 1,002.

And that highlights another major lesson: besides carrying a Naloxone kit, don’t consume drugs alone (and make sure one person stays ‘clean,’ Macleod noted).

At the heart of the video is how to identify a person in an overdose situation. Recognize the symptoms: unconsciousness resembling a sleeping state, dilated pupils with impaired breathing. This stage is critical, because brain damage can occur within minutes without sufficient oxygen. Take steps: arrange the victim in the recovery position, give them a shake. Try to stimulate breathing by rubbing the sternum (breastbone).

But first, open your kit and put on the rubber gloves. As Gus noted, if you accidentally touch a few grains of fentanyl-laced powder, you might keel over yourself.

The kit contains a breathing mask to cover the victim’s face in the event it progresses to mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.

The training kit contains three glass vials of (simulated) liquid Naloxone. In a real-life situation, the goal is to (quickly) inject the drug into the victim.

Where to inject? “Into the meaty part of the arm, into the thigh or into the butt,” Gascoyne said, adding, “through the pants is okay.”

Don’t expect any gratitude if the patient revives quickly, she noted.

“If the Naloxone does work, the user might be hostile.”

Another lesson: it is critical to call 911 and get medical help, because despite the initial recovery, the Naloxone could wear off within 20 minutes and the patient could crash again. And if the revived patient wanders off they might simply score more drugs again and repeat the overdose situation.

That 911 call will likely involve police. Macleod said one important point is to not focus on whether anybody is going to face legal consequences.

“We’re not there to get people into trouble. We’re there to get them out of trouble,” he said, adding, “However, if you do feel strongly that someone should be accountable [for causing the overdose], you can tell us that – after the emergency.”

Each student (and one Ha-Shilth-Sa reporter) took home a Naloxone kit, with instructions, such as don’t leave it in your car, because it must stay at (roughly) room temperature to remain effective.

Gus advised that she is on Facebook, and is now able to supply Naloxone kits to Tseshaht members on request.

Macleod said the goal now is to provide Naloxone workshops to as many Nuu-chah-nulth nations and communities as possible.