The First Nations Health Authority is encouraging more people to be screened for cancer, after a long-term study shows significantly lower survival rates among B.C.’s Aboriginal peoples.

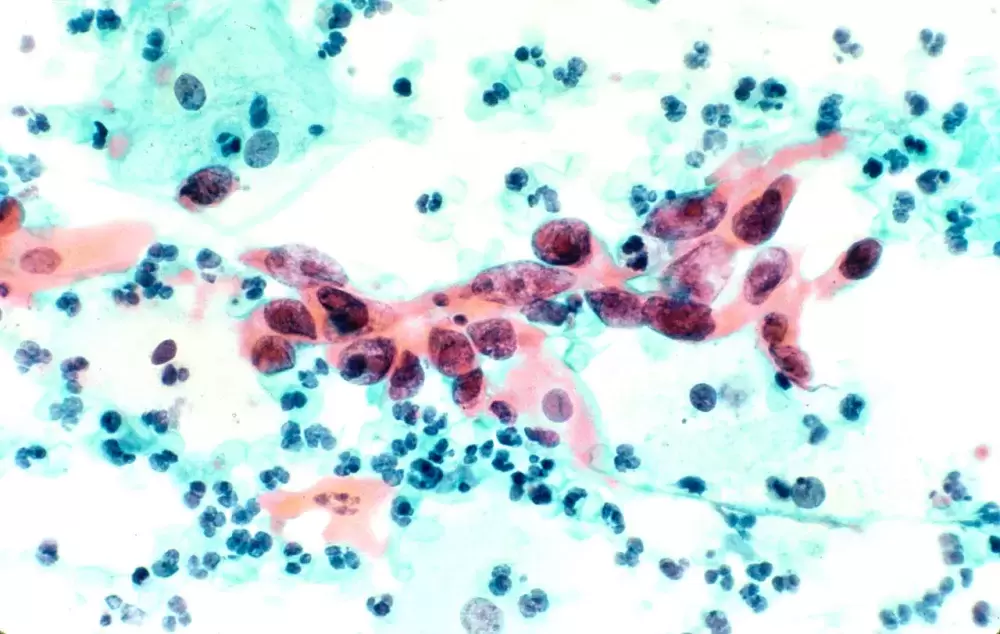

This May the FNHA launched the Screen. For Wellness campaign, a messaging initiative that stresses the importance of early cancer detection for the province’s First Nations peoples. The campaign focuses on breast, cervical and colorectal cancer, which were identified as the most common forms of the disease in a joint study published by the FNHA and BC Cancer in September 2017. To promote early detection, Screen. For Wellness encourages women over 40 to get a mammogram, even if they have no symptoms of breast cancer, while females aged 25 to 69 who have a cervix should regularly get a Pap test in case cervical cancer is present. The campaign also encourages women and men between 50 and 74 to screen for colon cancer, regardless of their lack of symptoms.

The cancer study examined 4,106 of B.C.’s First Nations people from 1993-2010, finding that although the overall incidence of cancer was lower among First Nations than the province’s non-Indigenous population, survival rates for Aboriginal people was notably lower. The study cites that in 10 of the 15 cancers that are most commonly found in women, and with 10 of the 12 cancers listed affecting men, First Nations are less likely to survive after a diagnosis than the rest of the province.

This has led the FNHA to promote the need for more Aboriginal people to get screened for the disease.

“Our ultimate goal with this campaign is to increase participation in cancer screening programs so that First Nations people detect cancer earlier to improve treatment and chances of survival,” said Dr. Shannon McDonald, the health authority’s acting chief medical officer in a statement released May 15. “We’d like to see people having ongoing conversations with their friends, families and communities about making cancer screening part of their wellness journeys.”

Cancer is the leading cause of death in Canada, and two in five people will have the disease at some point in their lifetime, according the Canadian Cancer Society. In B.C., breast cancer is the most common form found in First Nations women, while prostate and colorectal have the highest rates of incidence among Aboriginal men, according to 2017 cancer study. Cervical cancer was also found to be 92 per cent more common in First Nations women than other females in B.C., while colorectal cancer was 39 per cent more likely to affect Indigenous men than other males.

Although colorectal cancer is one of the most deadly forms of the disease, survival rates are 90 per cent if it is detected early, stated the FNHA.

But this is more easily said than done for those who live in remote Nuu-chah-nulth communities along the west coast of Vancouver Island. Kyuquot is the most northern of these settlements, where at the local health centre a visiting physician or nurse practitioner is available every two weeks by appointment, according to Island Health.

This limited availability does not help to encourage cancer screenings for Kyuquot residents, said Matilda Atleo, the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council’s community health promotion worker.

“They would have to go to their doctor, and they probably wouldn’t go unless they had signs,” she said, adding that regular cancer screenings might not be a common concern for those in remote communities. “I don’t think they even think about, unless they might have a symptom.”

For the last two years Atleo has worked to promote the awareness of cancer among Nuu-chah-nult-aht by helping to plan an annual dinner hosting Tour de Rock riders, who pass through Port Alberni each year as they raise funds for cancer research and support. This year the fundraising police officers will be hosted by the Huu-ay-aht First Nation at a venue in Port Alberni.

“A few years back I would watch the Tour de Rock riders ride right by us here,” said Atleo.

A few years ago Atleo organized a breast cancer screening at Maht Mahs on the Tseshaht reserve. She met people at that event who had been reluctant to get tested in the past.

“There were actually women who had never been tested,” said Atleo. “They just felt comfortable coming here.”

After the release of the joint cancer study in 2017, a strategy to improve outcomes was published at the end of the year by the FNHA in collaboration with BC Cancer, Métis Nation British Columbia and the BC Association of Aboriginal Friendship Centres. Improving Indigenous Cancer Journeys in BC lists “promoting cultural safety and humility in cancer care services” among its top priorities, but little mention is made in the document about the importance of traditional medicine.

Atleo has heard of many Nuu-chah-nulth people who incorporated traditional healing practices into their means of coping with cancer.

“We might have people who have cancer and they’re trying to use alternatives,” she said.

More information about the First Nations Health Authority’s campaign is available at www.screenforwellness.com.