The remains of several individuals are coming home this summer, 80 years after they were removed from a whaling shrine in Ahousaht.

In early July members of the First Nation plan to pick up the skeletal remains from eight individuals that have been in storage at the Royal BC Museum in Victoria for decades. Ahousaht Chief Councillor Greg Louie said eight cedar boxes are being made by member Wally Thomas to properly transport the remains for their burial in a graveyard in Ahousaht.

“We’re going to take our witwaak (security) and some of our spiritual people along with us and ha’wiih, if they’re available, to Victoria,” he said, noting that the remains will be placed in the cedar boxes on the preceding afternoon before they are taken to back to Ahousaht.

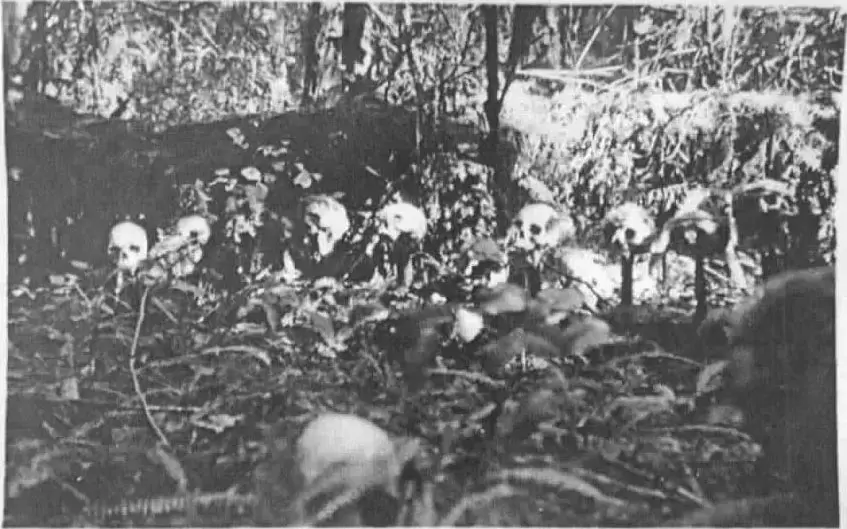

For years the remnants have been stored at the museum in a closed tote box. Its contents include three skulls and three separate jaw bones, remains from six individuals that were removed from a whalers’ shrine in Ahousaht in the 1930s. According to the museum’s file on the remains, this shrine was “in a small glade near pool for bathing. Skulls set on small pegs driven into the ground.”

The bones were removed by Rev. George Kinney, a missionary stationed in Bamfield in 1934 who travelled the west coast of Vancouver Island on the MS Melvin Swartout.

Louie said that Ahousaht was first informed of the remains in February, and the band’s council members travelled to Victoria in May to meet with archaeology curator Grant Keddie and other museum staff.

“When we sat down with him he told us straight out that these were stolen,” said Louie, adding that the remains are particularly important to the First Nation due to the high status whalers held in the community. “Once we found out that is was from a whalers’ shrine it upped the real importance of this.”

A skull and jaw bone from two other individuals will also be transported by Ahousaht members. These remains were taken from a location at the north end of Flores Island in 1960 “protruding from the ground,” with a nail imbedded in the skull, according to the RBCM file. Brought to the museum in 1969, the museum’s records do not disclose who removed these human remnants from Ahousaht territory.

The skulls and jaw bones taken from the whalers’ shrine arrived at the museum in 1958. RBCM repatriation specialist Lou-ann Neel suspects this could have been following Kinney’s death. The reasons for the initial removal are open to speculation.

“Gone are the days when you come into our communities and you take our people, take our remains,” said Louie. “I don’t know what the reverend’s plan was to do with these remains. Did he have an intention to sell them, did he have an intention to have some kind of gain from these?”

“I don’t think there was anything about profit in it,” said Neel. “People back in those days just seemed to think they were abandoned places and just took things.”

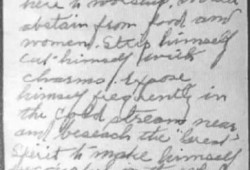

Along with a photograph that the reverend took of the whalers’ shrine, a handwritten note accompanies the museum’s file, indicating Kinney’s attempts to understand what he was removing from the sacred site.

“An Ahousat Indian shrine,” wrote Kinney. “An Indian who came here to worship would abstain from food and women. Strip himself, cut himself with charms, expose himself frequently in cold streams near and beseech the ‘great’ spirit to make himself successful in the whale hunt or gambling at lahal. He would beseech the spirits (of the skulls) to aid him.”

The whale hunt held a central importance to Nuu-chah-nulth communities along the coast, providing sustenance for tribes throughout the year. Those who partook in the dangerous endeavor were held in high regard, and underwent culturally specific preparations before pursuing the cetaceans.

As whaling has not taken place on the west coast of Vancouver Island for generations, Louie sees the repatriation of the remains as an educational opportunity.

“It’s an education for society in general,” he said. “It would be an education for our people here, definitely, who have never, ever experienced whaling, never heard of whalers or how they prepared themselves, and how whalers were upheld as important people of high status in communities.”

“It goes back to society also acknowledging who the Ahousaht people really were - they were whalers,” added Louie. “Our people are always in courts about defending ourselves about how we lived and what we did to survive. Here’s a real testimony of what whalers did.”

The repatriation of the Ahousaht remains is part of a larger initiative the museum has been undertaking to help return cultural artifacts and human remnants to their rightful homes. In 2016 the provincial government began allocating funding to support First Nations with this process, and 25 applications are currently being reviewed for grants of up to $30,000.

Neel said hundreds for bone fragments have already been returned from the museum’s collection, but many remain in storage.

“There are over 400 different fragments, some skulls, some portions of bones from different areas around B.C.,” she said, adding that the Cowichan Tribes repatriated some remains within the last two years.

When the Ahousaht group places the remains in their cedar boxes on June 13, it will be the first time any of the First Nation’s members have seen the remnants of the whalers in several generations. Louie said that cultural protocol led the members to not open the tote when they visited the museum in May. Before they entered the museum’s storage room a chant and prayer were performed, followed by a sense of “high emotion” with the need to bring their ancestors home to rest, said Louie.