The Maa-nulth Treaty Society has called a recent killer whale critical habitat order into question by filing for a judicial review of the DFO’s consultation process.

Larry Johnson, chair of Maa-nulth’s fisheries committee, said Fisheries Oceans Canada’s announcement in December to designate a large section of offshore water west of Barkley Sound as killer whale critical habitat could be contravening stipulations of the Maa-nulth treaty. The DFO’s critical habitat order ties the offshore section to regulations under Canada’s Species at Risk Act.

“It’s written right into our final agreement that the Species at Risk Act must consult with wildlife tables, and our fisheries committee is considered one of those tables,” said Johnson. “There’s prohibitions in SARA that will potentially impact our treaty fishing rights – and aboriginal rights for that matter.”

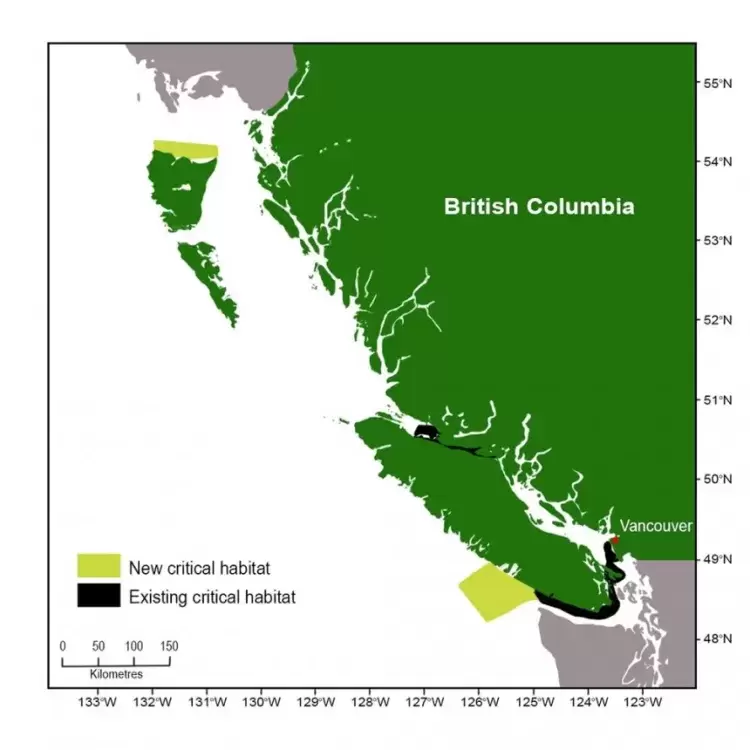

On Dec. 19 Jonathan Wilkinson, Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard, announced that critical habitat for killer whales on B.C.’s coast will more than double to 10,714 square kilometres. This adds to stretches of critical habitat along the south and northeast of Vancouver Island with designated areas north of Haida Gwaii and a large block directly west of Barkley Sound, which includes Swiftsure and La Perouse Banks.

This designation is being imposed to help protect the northern and southern resident killer whales, which are respectively listed as “threatened” and “endangered” under the Species at Risk Act. Although the DFO has not announced any restrictions to fisheries, the declining availability of chinook salmon is cited as a key threat to killer whales, leaving some to fear tightened harvest limits this year off the southwest coast of Vancouver Island.

“That really takes quite a lot of our Maa-nulth domestic fishing area,” said Johnson of the new critical habitat. “Maa-nulth totally agrees that we need to save the killer whales, but are we doing it in a fashion [that’s] a detriment to others?”

“We know that Canadians care deeply about these whales,” stated Minister Wilkinson in his December announcement. “These new critical habitat areas will ensure that the ocean space that the whales frequent and forage for prey is protected for generations to come.”

But Johnson questions if enough evidence was collected to issue the critical habitat order, including gathering input from those who have called the offshore waters home for thousands of years.

“There was a whole bunch of opportunity for them to have meaningful consultation with us, because we had responded on the initial recovery strategy,” he said. “We had requested meetings and we requested information that we didn’t get responses to.”

“There was too many data gaps in terms of why it became an emergency, why they had to add all of this other critical habitat,” added Johnson. “I don’t see the science that backs up that La Perouse Bank is critical habitat.”

Among the scientific studies cited by the DFO to inform the critical habitat order was an advisory report issued in 2017. This study drew upon vessel surveys and acoustic monitoring of whale vocalizations throughout the year off of southwestern Vancouver Island, around Swiftsure Bank.

“Resident killer whales were detected acoustically in the area on one out of every three days, on average, during 2009-2011,” stated the science advisory report. “The area is important for [southern resident killer whales] during summer, when groups make foraging excursions to the west of the currently designated critical habitat, and in winter when whales are mostly absent from the identified critical habitat, but frequently use this area.”

A judicial review of the critical habitat order would entail an assessment of the correspondence between federal departments and Maa-nulth. As one of the few modern-day treaties in British Columbia, the Maa-nulth Final agreement came into effect in 2011, setting out the rights and benefits that are tied to the land and resources of five Nuu-chah-nulth nations: Huu-ay-aht, Uchucklesaht, Toquaht, Ucluelet and Ka:'yu:'k't'h'/Che:k'tles7et'h'. The treaty was signed by the First Nations, British Columbia and Canada to bring certainly to the five nations’ aboriginal rights in their territorial land and waters.