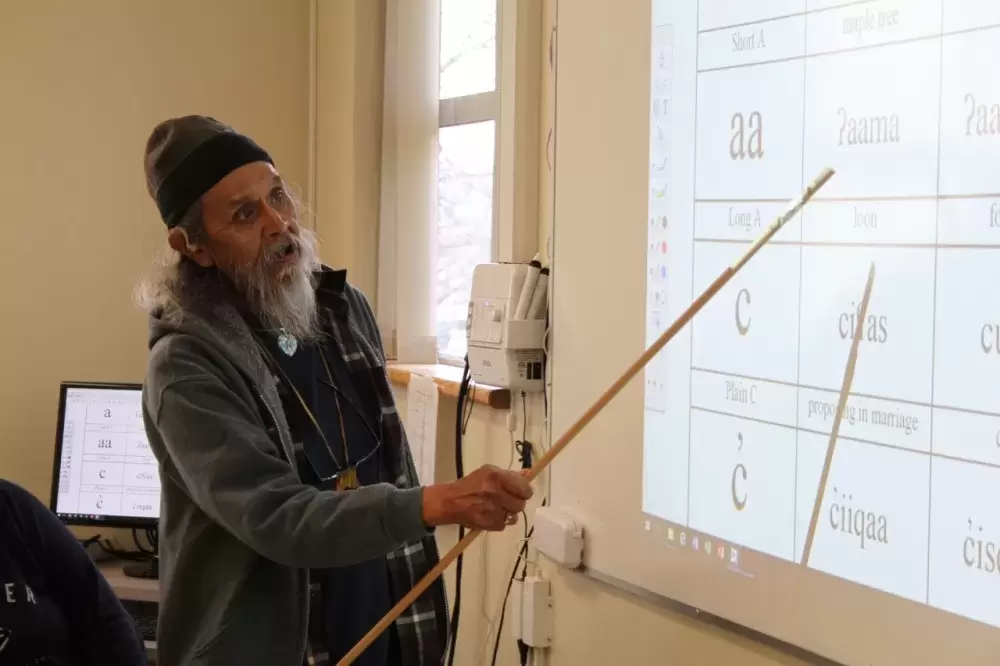

On a Wednesday evening in April, Chuck Watts stands before a classroom at Port Alberni’s North Island College campus, leading the group through the extensive Nuu-chah-nulth alphabet. With a pointer in hand, the adult student goes through a portion of the list of 44 characters, pronouncing words like kakaw`in (killer whale) and ?iihtuup (grey whale) before the class repeats.

After two semesters that began in September, this is the last class of Introduction to Nuu-chah-nulth Language, a time that Chuck Watts reflects on as a personal awakening. Although both of his parents were fluent, while Chuck grew up in Port Alberni they kept the ancestral language to themselves, only speaking to Watts in English.

He moved away for 34 years, and ended finding a career as a tour guide in Vancouver. But finally learning Nuu-chah-nulth became a foremost goal upon returning to his home community last year.

“When I came home all my friends, my school mates, passed on,” said Watts. “I felt, ‘Oh, god, I feel so lonesome’.”

“It’s something that I’ve always wanted to do but never had the chance because I was living in Vancouver,” he continued. “I’m so proud of it. The native in me is coming out now.”

With a heavy emphasis on repetition, students in the course become accustomed to pronouncing the complexities of a language that, until a written alphabet was formally adopted in the late 20th century, for countless generations existed only in the spoken form. This allowed Luke George to finally understand a prayer he had in his office, which begins as Wai kas^ nas H=aa >api H=awi> (Praise the light of the day, the creator).

“Now I can read that prayer and say those words the way it’s supposed to sound - before I was just guessing,” said George, who admits that it can be challenging to learn the many Nuu-chah-nulth sounds that don’t exist in English. “The toughest part is some of the symbols.”

George found the best place to practice speaking was the forest, where the only one to listen to his pronunciation was his dogs.

“For me, my church is the outdoors, walking with my dogs and listening to the birds,” he said. “Growing up, I knew some words because it was spoken in my house from my grandmother and my great-grandmother.”

Jane Jones said the introductory course, which is scheduled to run again in September, resembles one she taught from 1996-98 at NIC with Angie Joe.

“Last term in September we had a waiting list of 14 people, so I’m encouraging our Nuu-chah-nulth people to register in May if they really want to take the course,” said Jones.

While attaining fluency might be a far off aspiration for students, the course’s immediate value is in connecting students with their heritage. The last session was taught in the Barkley Sound dialect.

“I don’t know about fluency, but the language class will give them back their identity,” said Jones. “It’s very emotional; this is not just learning the language, it’s reclaiming who you are.”

This is particularly the case for those known as silent speakers, people who understand Nuu-chah-nulth but gave up speaking it long ago. Angie Joe, who assisted Jones to teach the introductory course, finds that she now feels safe to speak her dialect, thanks to the supportive learning environment of the classroom. At the age of seven Joe left her home in Sarita to attend the Alberni Indian Residential School until she was 16.

“The more I hear it, the more it comes back to me,” said Joe of Nuu-chah-nulth.

For years Tom Watts didn’t see the value of learning a language that he couldn’t commonly speak to people, but this attitude changed when he stepped into the introductory course in January.

“I could understand what they were saying,” recalled Tom, whose grandmother and parents spoke Nuu-chah-nulth when he was young. “I have five native names, but I really didn’t know the meaning of them and where they came from.”

Like the other students, Tom intends to continue learning his ancestral dialect after completing the introductory course.

“I hate to see it come to an end because I’ve learned so much in such a short period of time,” he said. “I like teaching my grandchildren now, but they learn so fast.”

George plans to bring out an old collection of VHS tapes with people speaking Nuu-chah-nulth that his late grandmother left to him.

“I’m going to get them converted to disk or a file so that I can listen,” he said. “My next goal is to try to pick up on the language.”