Day school survivors should be preparing claim forms soon through a long-awaited class action settlement with awards ranging from $10,000 to $200,000.

The final hurdle in litigation against the Government of Canada — which operated “federal Indian day schools” in roughly 600 communities across the country for more than 60 years —was cleared Aug. 19 in the form of a decision by the Federal Court of Canada. Justice Michael Phelan found that the settlement agreement as proposed in March is “fair and reasonable” and in the best interests of survivors.

“Finally, it’s here,” said Richard Watts, resolution health-support worker with the Teechuktl program in Port Alberni. “The day has come.”

Compensation claim forms will be made available through the class-action website, indiandayschools.com (a draft version only is currently posted). Forms will be accepted for the next four months, subject to appeals, according to Gowling WL, the law firm handling the settlement.

“Don’t wait until the deadline to file,” Watts advised.

There is a 90-day opt-out period for survivors who do not agree with the terms of settlement.

Pursuit of justice was underway when Watts joined Teechuktl in 2011. Survivors are in their senior years. About 1,800 of them pass away yearly among a total of 120,000 survivors across the country. The original lead plaintiff in the class action, Garry McLean, died of cancer only weeks before a settlement was reached last winter.

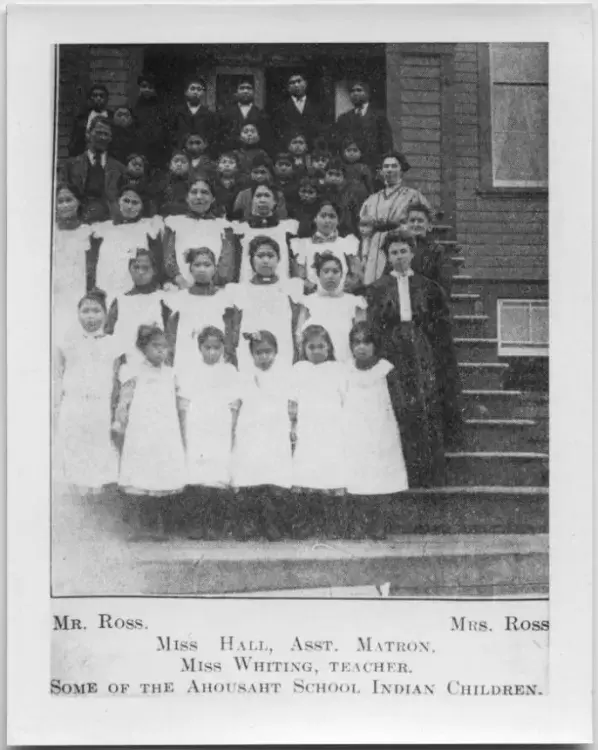

Starting in the 1880s, day schools were operated on reserves by churches and were later taken over by the Canadian government. Day school students are different from day scholars, the name given to students who attended but did not reside at residential schools. Watts said both day school students and day scholars were part of the residential school settlement process at the outset.

“They wanted to go to court but were convinced to step aside,” he explained. “They didn’t want to hinder the (residential school) case.”

For more than six years, the action by McLean and fellow Manitoban plaintiffs (Roger Augustine, Claudette Commanda, Angel Sampson, Margaret Swan and Mariette Buckshot) remained in limbo. Their counsel at the time had difficulty marshalling resources to continue the litigation and no other firms were prepared take it on until Gowling stepped up and launched the case three years ago.

Lessons were drawn from the residential school process and hearings held by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Day school hearings were held by an adjudicator rather than in a courtroom. They were still difficult for people, said Watts, who attended some of the sessions.

“They wanted to make it less judicial,” he said. “They wanted to make it quicker. These people were passing away as we went through the process.”

Part of the intent was to avoid retraumatizing survivors any more than necessary to document their experiences of abuse, which were similar to those of residential school survivors.

“These schools had profoundly negative effects on many of their students,” Justice Phelan wrote in his decision. “The representative plaintiffs were exposed to a program of denigration, psychological abuse and physical violence often for such simple things as speaking their own language to others of their community at the schools. This experience had a deep and lasting impact on the representative plaintiffs, impairing their sense of self-worth and impeding their relationships with others and leading to personal issues with substance abuse among the many ills that resulted from that abuse.”

The settlement agreement stipulates that a claims process must be “expeditious, cost effective, user-friendly and culturally sensitive.” A $200-million legacy fund, recognizing the multi-generational impact of the experience, is part of the settlement. The fund is intended to support efforts in commemoration, health and wellness, language and other cultural initiatives.

To be eligible for compensation, individuals must have attended at least one of the day schools funded, managed or controlled by Canada. A list of the schools is included on the Gowland website, indiandayschools.com. Five day schools that operated in Nuu-chah-nulth territory are included: Ahousaht, Yuquot, Kyuquot, Ucluelet and Opitsaht. Two other day schools located in Hesquiaht and Tseshaht territories did not meet settlement criteria.

In the late 1940s and early ’50s, Marie Nookemus of Bamfield attended the Ucluelet day school. Two of her nieces and a nephew attended at the same time. She recalls the embarrassment and humiliation. Children who knew only Nuu-chah-nulth were ridiculed for speaking their native language.

“You felt ashamed when you were yarded down the aisle,” she said, recalling how one staff member would remove his belt to threaten them.

“I still live with it,” she added.

At school, Nookemus learned to act as a “guardian” for her younger relatives, much like an older sister would, trying to protect them.

Watts said survivors should be aware of the pending claims process and be prepared to provide testimony of their experiences.

“They’re going to be having hearings again, probably using an adjudicator. People should be encouraged to sit down and start talking to other former day school students,” he suggested. This may help jog their memories of school experiences long ago.

He also cautioned survivors not to expect settlement cheques anytime soon.

“Don’t hold your breath … but here we are,” he said.

The plaintiffs paid tribute to Garry McLean in a letter posted on the settlement site.

“The settlement achieved through Garry’s determination honours the principles he and so many of us have fought for,” they wrote, listing the priorities of inclusivity, dignity, consideration of future generations and justice.