B.C. MLAs have voted unanimously to give first reading to the Declaration of the Rights of First Peoples Act, a human rights bill hailed by Indigenous and non-Indigenous leaders as a major milestone on the path to reconciliation.

“Let’s make history,” declared Scott Fraser, minister of Indigenous relations and reconciliation, as he introduced the bill in the Legislature on Thursday.

Expected to sail through subsequent readings, Bill 41 makes B.C. a trailblazer in the advancement of Indigenous rights, the first province to pass into law the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). The law is seen by many as a key step in the transformation of the relationship between Indigenous peoples and the B.C. government, answering calls to action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

“And it’s about time,” said Cheryl Casimer of the B.C. First Nations Summit in her address before the house. “The province of British Columbia is finally recognizing that we do indeed exist as peoples, peoples with long and unique histories, peoples with deep connections to our territories, peoples with inherent jurisdiction and governing authority, people with the right to determine ourselves what is best for ourselves and our respective territories.”

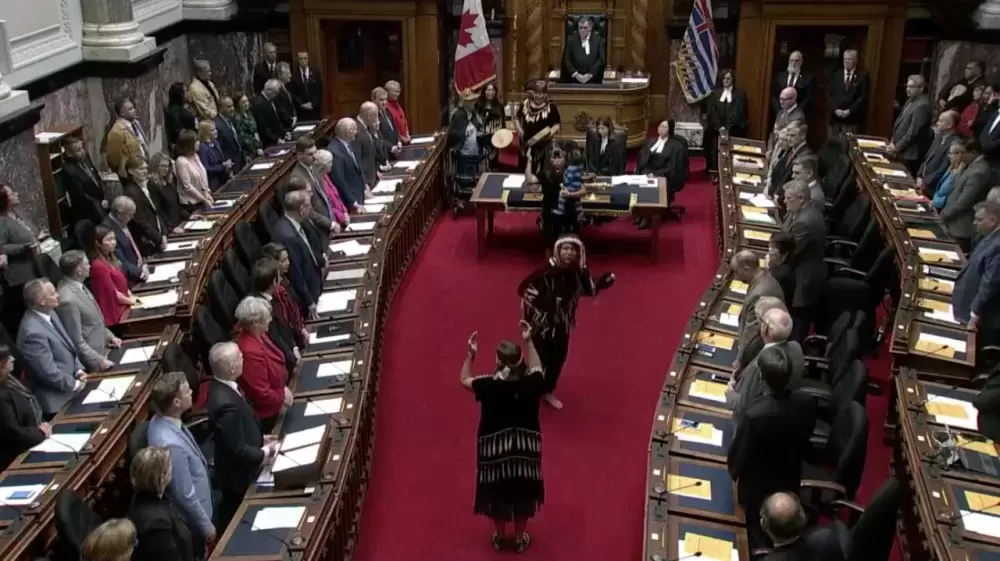

The legislative session was temporarily closed Thursday to allow First Nation participation prior to Legislative proceedings. After a prayer by Shirley Alphonse of Sooke First Nation, the occasion was celebrated in song by Butch Dick and the Lekwungen Dancers of Songhees First Nation.

Like other Indigenous leaders who travelled to Victoria for the occasion, NTC President Judith Sayers had a front-row seat, hearing speakers and watching the historic drama play out. In the public gallery watched other Indigenous politicians, including Quebec MP Romeo Saganash — who fought unsuccessfully in the House of Commons earlier this year to have federal laws harmonized with UNDRIP — and newly re-elected Independent MP Jody Wilson-Raybould.

“Everybody was so up and excited that this is actually happening,” Sayers said. “It was quite the day.”

Every leader who spoke on behalf of B.C. First Nations, including Grand Chiefs Ed John and Stewart Phillip, BCAFN Regional Chief Terry Teegee and Casimir, received a standing ovation, she noted.

John said the legislation cannot be simply symbolic, that it should “bring justice to the issues.”

“I call on you to be brave,” he said. “Change does require courage.”

For Sayers — who was directly involved in crafting UNDRIP at the UN two decades ago while representing the Four Nations of Hobbema in Alberta — the legislation is welcomed but she has concerns with some aspects.

“It’s not perfect, but we can work with this,” she said Friday after returning to Port Alberni. “This is a good day. It’s a good thing. I just think it could be better, it could be stronger.”

While the NDP government cited collaboration with First Nations in drafting the bill, only the B.C. First Nations Leadership Council was directly involved. Other Indigenous leaders were invited to view the legislation a few weeks ago after signing a non-disclosure agreement, too late in the process to provide substantive input.

“If Indigenous people had drafted this, it would look a lot different, but it’s what we will work with,” Sayers said.

The bill lays out an action plan to begin addressing the task ahead, an estimated 5,000 laws that will need to be brought into compliance. Those will require prioritizing.

“As Indigenous peoples, we need to decide what are the most important provincial laws affecting Nuu-chah-nulth concerns the most and put them in line with UNDRIP,” Sayers said.

There are some definitions of shared decision-making and consent within the legislation that raise NTC concerns. Additionally, trying to negotiate First Nation interests with the province on a project-by-project basis could be an onerous requirement, Sayers suggested.

“I just think it’s a lot of work to achieve what needs to be achieved,” she said. “I wish there could have been another way of doing that.”

As laws are modified or drafted, they will be aligned with the UN Declaration. Other elements include:

- Annual public reporting to monitor progress.

- Discretion for new decision-making agreements, with clear processes, administrative fairness and transparency, where decisions directly affect Indigenous peoples and mechanisms exist in legislation.

- Recognition of additional forms of Indigenous governments in reaching agreements. These could take the form of multiple nations working as a collective, or hereditary governments as determined by citizens of the nation.

While the legislation will be watched closely by other provinces, it is unlikely to have a direct impact on treaty talks with the federal government that have dragged on for years. That impetus is more likely to come from a new treaty framework, adopted last week at the First Nations Summit.

Bill 41 is expected to pass final reading by the end of November.

“This is the easy part,” Sayers said, adding that what is needed now is political will and open minds to find new ways of working together.