Amid the heated treaty negotiations between Nuu-chah-nulth nations, the province and the federal government, Ha-Shilth-Sa reporter Denise Titian was assigned to spend a week in Tsaxana in November 1996. She had to bring along her daughter June, who was 14 at the time and struggling with math, to the Mowachaht/Muchalaht settlement near Gold River. Fortunately help came from Denny Grisdale, who served as chair of the treaty table.

“During breaks Denny offered to sit with her,” recalled Titian. “He sat and he tutored her and got her through her math that week.”

Grisdale would continue in this role until five Nuu-chah-nulth nations reached an Agreement in Principle in 2001, laying the foundation for the Maa-nulth treaty in place today.

“He had a profile of wanting to get things done,” commented Robert Dennis Sr., long-serving and current chief counsellor of the Huu-ay-aht First Nations. “[Grisdale] did his best to move the negotiations along the best he could, and in quite a few situations probably facilitated us to getting out of an impasse rather than staying stuck on issues.”

“He was chairing the meetings to make sure everybody was living by their own rules,” remembered Tseshaht member Richard Watts, who was a chief negotiator with the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council at the time.

As a mamałn̓i, or white person, his presence during the treaty sessions matched his reputation for advocating on behalf of Nuu-chah-nulth people as they found their way in a rapidly changing world – decades before the term ‘reconciliation’ became common lingo among governments and organizations.

Grisdale educated generations of students in the Alberni School District, including during a particularly sensitive time when youngsters were transitioning from the assimilationist Alberni Indian Residential School (AIRS) into the mainstream system. Robert Dennis looks back on Grisdale’s influence as a gymnastics, basketball and soccer coach at A.W. Neil in the 1960s.

“He used to say when we came from elementary school into junior high, if you were First Nations you were practically guaranteed a position on the soccer club,” he said. “Back then the soccer players from residential school were pretty good. That was basically all we had to do in our spare time, was to play soccer. So it was almost soccer around the clock for a lot of us.”

“I liked him as soon as I met him,” added Dennis, who attended AIRS before he entered A.W. Neill. “I think that he looked at native people in a very compassionate way. He knew that we were all coming from a background where we didn’t want to be, and that was in the residential school.”

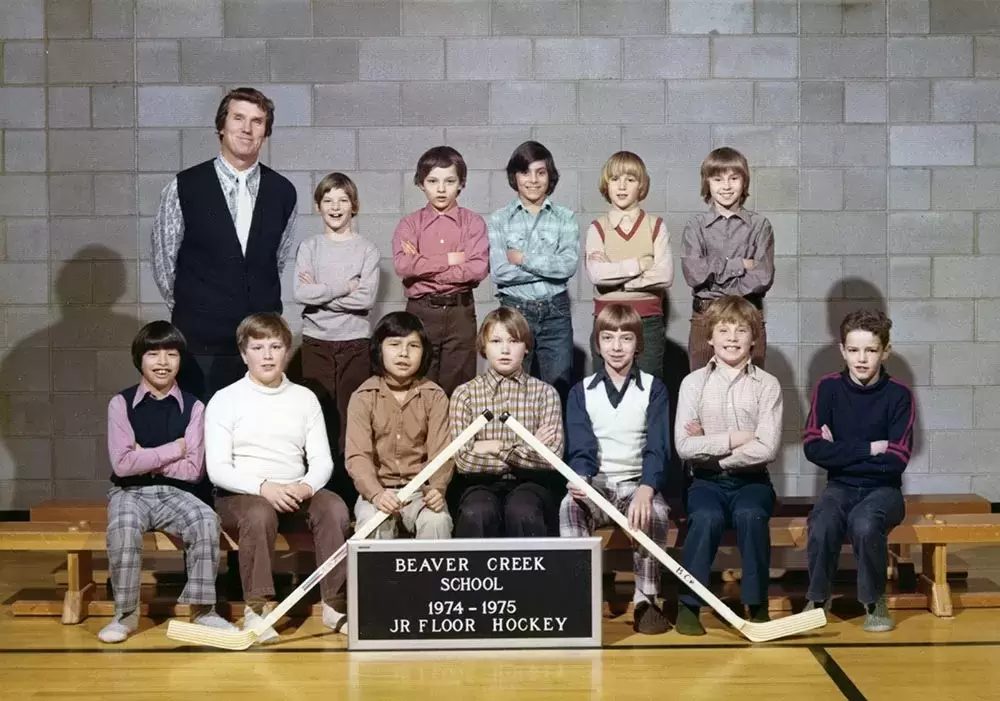

Pam Craig, chair of the Alberni District School Board, remembers Grisdale when he was principal of Beaver Creek School, which her son attended in the 1980s.

“It was like a giant family that school,” she said. “I know he worked very hard to include the First Nations families, and the parents in particular, to make them feel comfortable and be involved.”

Craig first knew Grisdale from his years with the Alberni Athletics, the storied senior A men’s basketball team that would win multiple national titles in the post-war era. Craig’s father’s cousin was Fred Bishop, the Athletics’ coach.

“Many times after the team had a big game or a big tournament they would all come back to my parents’ house,” said Craig. “My mother would have jelly and buns for the whole group.”

Tom Watts was on the team in the 1960s, winning a senior A championship with Grisdale in 1965.

“We won every game except two games all year,” he said.

A close friend until Grisdale’s passing on Oct. 21 at the age of 86, the Tseshaht member felt Grisdale treated him like “a close relative”. But at times Grisdale’s continued support to First Nations people made him unpopular with others in Port Alberni, said Tom Watts.

“He was always arguing for the natives,” he noted. “He would have to explain to the people why we were not stupid drunkards, alcoholics and we don’t get our houses, our cars and everything all free.”

During Port Alberni’s heyday as an affluent forestry town, such concepts were not unusual in the schools. Richard Watts attended A.W. Neill in the 1960s, where Grisdale was a teacher.

“In this time racism was quite open and considered normal,” he said. “It was considered normal behaviour to pick on everybody, Chinese kids, East Indian kids – and I’m saying it the correct way, they were saying it differently.”

But Grisdale persevered through the years, and by 1988 it became clear the education system was changing for Port Alberni’s many Nuu-chah-nulth students. Grisdale became the district’s first principal to oversee First Nations education, assessing the role of Aboriginal content in the region’s public schools. With his help the NTC would begin a training program for cultural teachers and counsellors that year, an initiative that would evolve into the existing Nuu-chah-nulth Education Worker program.

“It’s hard to understand a person that is not a native, protecting the native culture and our ways,” reflected Watts. “He was always happy to see me.”

Denny Grisdale is survived by his wife Sharon, brother Jim, children David and Jill, stepchildren Greg, Kevin and Katharine, as well as grandchildren Evan, Gareth, Brendan, Zachary and Aidan.