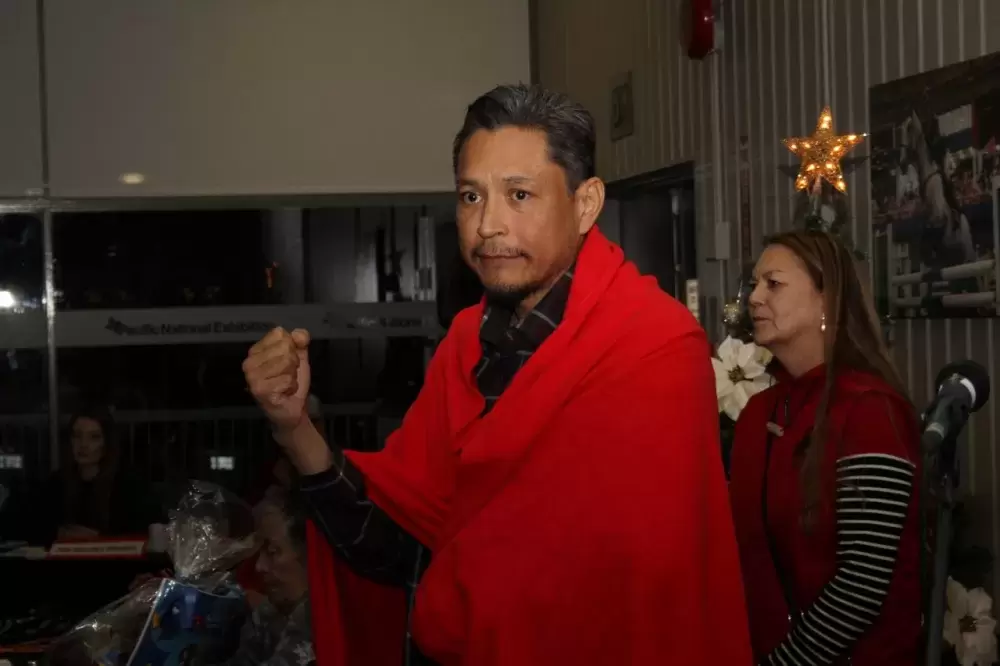

On an evening in early December, David Dennis looks out into the warmth of a crowded room in east Vancouver, absorbing the applause into his struggling frame. The 44-year-old is wrapped in a red blanket, a symbol of support for his battles and advocacy since being diagnosed with end-stage liver disease in July.

The blanketing from the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council’s Teechuktl staff came when Dennis was celebrating six months of sobriety – but still waiting to hear from doctors if his condition could sustain a transplant necessary for long-term survival.

“We’re trying out if there’s a third party that can look at the file to tell us whether or not that’s true - but to be honest, I’ve been fighting it for so long, I’ve had to focus on just my health for a good six months,” said Dennis of the transplant possibility. “I’m still, in a sense, dying. My liver is deteriorating still, but there’s portions of it that are recovering.”

After he was diagnosed with end-stage liver disease in July, the father of five was informed that he would be excluded from BC Transplant’s organ donor registry due to a policy requiring abstinence from alcohol for six months. Along with the Union of BC Indian Chiefs and the Frank Paul Society, which Dennis leads as president, he filed a complaint to the BC Human Rights Tribunal, stating the policy was discriminatory.

The group’s complaint states that Dennis has abstained from drinking since June 4, and was being unfairly assessed for his alcohol use disorder due to a policy with “little or no scientific support”.

“The abstinence policy places Mr. Dennis’ health at risk, potentially fatally, by delaying his access to a transplant,” reads the complaint. “It is also an affront to his sense of dignity, respect and self worth.”

This complaint challenges the lawfulness of the six-month abstinence requirement, argues the Union of BC Indian Chiefs.

“The abstinence policy discriminates against Indigenous peoples, who have disproportionately higher rates of alcohol use disorder largely due to the centuries of racist and harmful colonial policies implemented at all levels of Canadian government, but especially through the intergenerational traumas of the Indian residential schools on Indigenous families and communities,” stated a press release issued by the UBCIC in August.

This pressure, and the media attention generated by the roadblock Dennis faced, appears to have quickly changed BC Transplant’s stance on the abstinence requirement. In September the agency spoke of “new, emerging clinical evidence” that led to the reconsideration of the six-month abstinence requirement.

“The new approach offers the potential treatment option of liver transplantation for those who have abstained from alcohol for less than six months and are regarded to have low-risk of post-transplant alcohol use once assessed by the transplant team,” stated BC Transplant, although alcohol consumption is still discouraged once a liver transplant is done. “A period of abstinence from alcohol is still needed because the natural recovery of liver function can occur, reversing the need for a transplant.”

The provincial agency also noted the need to “destigmatize alcohol use disorder” while assessing patients. Dennis believes that this change in clinical practice will help other Nuu-chah-nulth patients at risk of liver failure.

“They’ve changed their stance, which will benefit ultimately a lot of our kuu’us people because they won’t be faced with the same barriers,” he said.

As for his health, a complication of Dennis’ liver disease has been hepatic encephalopathy, which entails deterioration in brain function. According to the Canadian Liver Foundation, this condition occurs when the liver fails to break down ammonia, which can be toxic for the brain.

“Ammonia is a molecule produced by bacteria within our intestine following digestion of food,” states the liver foundation. “It is normally removed by the liver. However, when the liver is damaged, ammonia builds up in the blood which can easily enter the brain.”

But pre-existing brain trauma could “accelerate the need” for Dennis to get a liver transplant, he said.

“That goes well back to my football days, but more recently in 2016 I was assaulted in the back of the head,” he recalled. “A young man who was beating up his wife at the time, I got involved and told him to stop. A scuffle ensued and I was punched in the back of the head.”

“Once you’ve got liver cirrhosis, it’s just a matter of time, whether you’ve got six months or six years, it depends on their monitoring,” continued Dennis. “We’re in a kind of monitoring stage right now.”

As he awaits the direction his medical treatment will take, Dennis was reassured by the unexpected flood of community support on Dec. 5 at the Nuu-chah-nulth gathering.

“I was just sidelined by it. The emotional response was a huge one,” he said. “I’m at that stage where I’m accepting the way things are, and obviously this generates a lot of feelings that people care. It’s a good demonstration that Nuu-chah-nulth people fundamentally are a good, caring people. When it comes to issues of health they stand together.”