Memories and photographs from survivors of St. Michael’s Residential School in Alert Bay line the walls of the Alberni Valley Museum as part of a new and powerful exhibit— Project of Heart and Speaking to Memory.

The exhibit is a combination between Speaking to Memory: Images and Voices from St. Michael’s Indian Residential School and the arts-based Project of Heart: Illuminating the Hidden History of Indian Residential Schools in BC.

The exhibit is put on through a collaboration between the museum, School District 70 (SD70) and the Nuu-Chah-Nulth Tribal Council education department. Every class in SD70 will have the opportunity to visit the museum and view the exhibit with Nuu-chah-nulth education workers. The museum visit is coupled with age-appropriate classroom learning that aims to build intercultural understanding, empathy and respect.

It acknowledges a time in Canada’s history when many young Indigenous children went away to residential schools, causing them to be separated from their families, their traditions, their language and their culture.

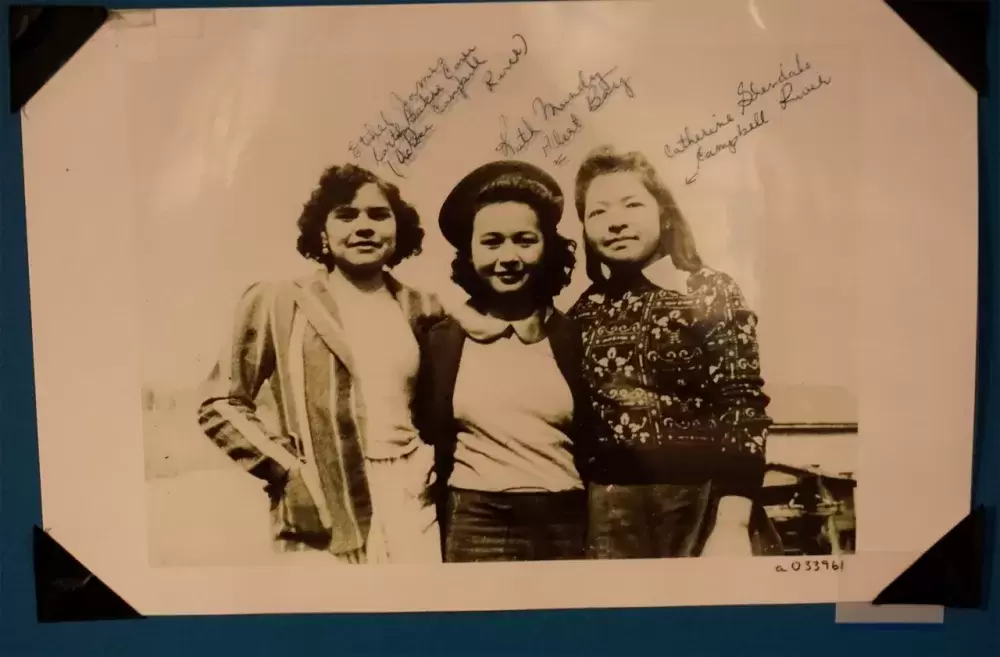

“[Speaking to Memory] is an absolutely amazing collection of photographs that were taken by a young student at St. Michael’s Residential School in Alert Bay from 1934 to 1944,” said Alberni Valley Museum coordinator Shelley Harding during the exhibit’s grand opening on March 5. “Her father sent her a camera and as far as they know it, it is one of the only collections of photographs taken by a student while a student at a residential school. It is pictures of her classmates and then coupled with that are interviews and statements from residential school survivors across the province.”

The Project of Heart exhibit is an interactive art project where SD70 students have the opportunity to give a message to residential school survivors during their visit to the museum. Students can write their message on a small paper tile that is stuck to a large poster board which will eventually be hung in each school.

“[Students] are seeing the faces of students who were in the residential school. We can read about it in a story, we can know that there was residential schools but these are the faces of the people and these are their actual words and their memories,” Harding said. “Such a high number of our population, of our citizens, have struggled through being forced into residential schools …and that is not what students in our public system know today. It’s important to hear also from survivors who are coming to them and telling their stories and memories.”

For the past several years, the exhibit has been travelling around the province to each school district to engage students in the issues that came from residential schools, reconciliation and to develop a sense of empathy in sending messages to survivors.

Dave Maher, SD70 principle of Indigenous education, said one of the goals of the Indigenous Education Program within SD70 is to have district-wide opportunities for all students and teachers to engage in learning surrounding reconciliation, as well as Nuu-chah-nulth and Indigenous worldviews.

“This [exhibit] was an easy one to say yes to because it’s a great opportunity to have everyone in our district engage in that type of learning,” Maher said. “It is only in acknowledging the past that we can move forward in a positive way so this is the experience that we’re bringing to our students here in SD70.”

Maher said in conjunction with learning from the exhibit, classroom teachings will occur for each grade. He said younger students will learn about the importance of home, family, the relationship to the land and the exploration of loss.

“In the older grades we get a little bit more historically based, still looking at what is the importance of family, what is the importance of language, cultures, traditions within our family and then what happens when that’s taken away,” Maher said. “Then the high school level is fact-based, history-based and they do work specifically surrounding the survivor accounts.”

Tseshaht elder Willard Gallic said the exhibit is an important way to tell the story of a dark time in the province’s and Port Alberni’s history.

“[The Alberni Indian Residential School] was built right here on our reserve without our consent. They just built it and went and grabbed all the kids, literally grabbed them,” Gallic said. “It’s not a very happy history, we’d like to leave it behind and start a new beginning and that’s what truth and reconciliation is all about—a new beginning. Some hurts are hard to let go. But we are moving on and things are getting better.”

Newly-elected Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council Vice-President Mariah Charleson said she was thrilled to see residential school students’ voices highlighted at the museum.

“I’m 32 years old and I was amongst the very first generation of people to not attend the Indian residential school in the community of Hot Spring Cove,” Charleson said. “I saw firsthand what the backlash and the inter-generational impacts that these federally-funded institutions had on their people and continue to have. The final school didn’t close until 1996 and it wasn’t until 2008 that we heard a public apology made from one of our old prime ministers—Stephen Harper.”

The exhibit is available for viewing until May 8.