Seamount life 400 kilometres off Vancouver Island’s west coast is showing effects of climate change caused by the burning of fossil fuels, scientists have concluded.

What makes the discovery — resulting from a scientific expedition last summer that included Nuu-chah-nulth representatives — of particular concern is its location. Undersea mountain ranges are among the most stable habitats on the planet, remote places where life-sustaining conditions have changed only on an immense geological time scale.

Research by a team of DFO scientists, using remote submarine cameras and data going back 60 years, shows that “rapid deep-ocean deoxygenation” and increasing acidification in the Northeast Pacific threatens volcanic seamounts, rich offshore oases of marine life.

“In the next 100 years, all the animals we found in this study are likely to face extinction,” said Cherisse Du Preez, a marine ecologist and deep-sea explorer who described the findings as “pretty shocking.”

“It’s a sobering thought considering we just discovered many of them,” she added.

Extirpation — or local extinctions — could come much sooner, within 40 years, she added.

Du Preez and two colleagues from DFO’s Institute of Ocean Sciences in Pat Bay, Tetjana Ross and Debby Ianson, released a study in mid August revealing seamount habitats are already showing signs of retreat. They reported their findings to an international audience of hundreds of scientific colleagues around the world, Du Preez said.

“Climate change is causing our oceans to lose oxygen and become more acidic at an unprecedented rate, threatening marine ecosystems,” they note. “In deep-sea environments, where conditions have typically changed over geological time scales, the associated animals adapted to these stable conditions are expected to be highly vulnerable to any change or direct impact.”

Based on their analysis, the upper 3,000 metres of the Northeast Pacific have lost 15 percent of oxygen since 1960.

While distant from the coastline, the area of concern is more than a dot on the map of the ocean floor. Scientists have circled the southern portion of the Offshore Pacific Bioregion — 133,000 square kilometres or four times the size of Vancouver Island — as a proposed marine protected area (MPA).

“We couldn’t explore this world until very recently,” Du Preez explained.

She said the area is vast and about two kilometres in depth, which makes the findings all the more significant.

“This is a very large body of water,” she said. “We’re talking about everything off the B.C. coast in your area. It’s extremely large. That’s one thing.”

Recent estimates indicated seamounts represent 28.8 million square kilometres of the earth’s surface, a greater area than tundra, deserts, savannah and other land-based habitats.

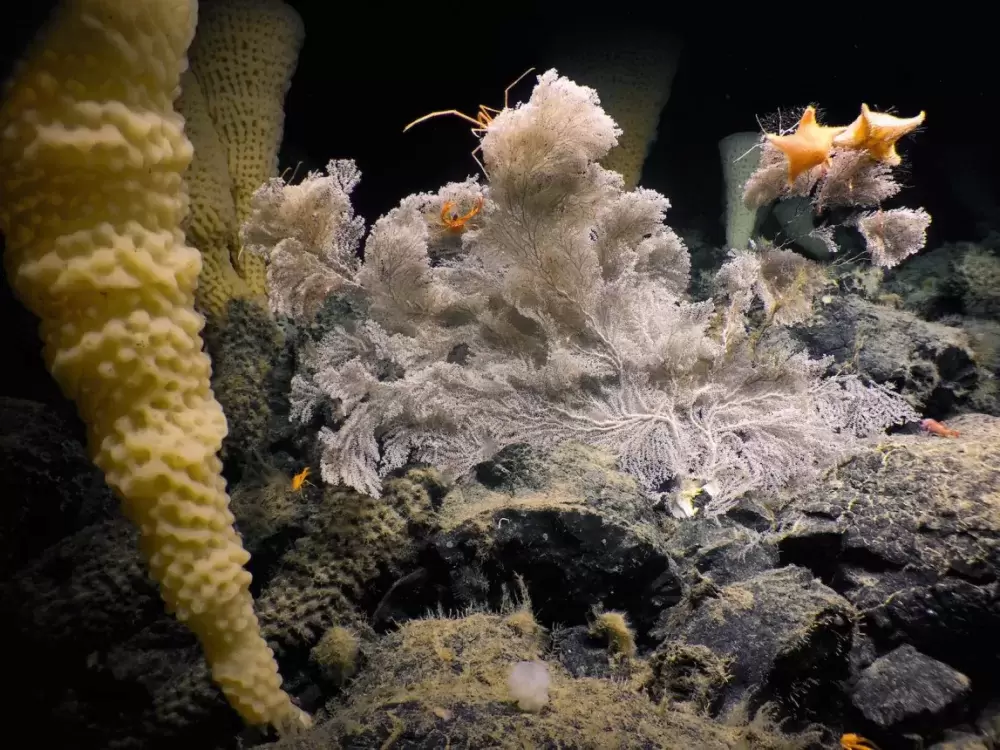

Another critical aspect is the nature of seamount animal life, which thrives around a diverse ecosystem of crustaceans, corals and molluscs that remain stationary throughout lengthy life cycles. The mountain is their one and only home over a long life.

“These animals, the fish, live to 200 years old and coral have been dated to 4,000 years,” Du Preez said. “We’re a blip in their lifetimes.”

‘Need to stand up’

To help pursue greater environmental protection of the seamounts, two Nuu-chah-nulth representatives, Uu-a-thluk’s Aline Carrier and artist Joshua Watts, took part in the 2019 expedition.

“We went out to sea knowing seamounts were under consideration for protection,” Du Preez said. “The movement to protect places in the oceans requires everyone involved to speak their minds, so it was very important to have First Nations cultural representatives on the voyage so that everybody has a level playing field and can consider the future of these treasures off the B.C. coastline.”

Carrier, marine emergency preparation co-ordinator for the NTC fisheries program, said she was not surprised to read of the research findings.

“While we were out there, we were also witnessing surface temperatures so high,” Carrier said, “It was in the middle of the Blob,” which is a recurring warm-water anomaly off the West Coast first identified in 2013. “The surface temperature was up to 19 C. That’s another influence of climate change, so we were kind of expecting to see something not necessarily positive.”

Understanding what’s going on hundreds of metres down in the ocean can shed light on what’s taking place closer to shore and increase public awareness, Carrier noted. The knowledge could benefit west coast First Nations.

“It might help to understand effects on coastal ecosystems because everything is related,” Carrier said.

Watts said he found seamount waters resonant with the Nuu-chah-nulth world view, “heshook-ish tsawalk,” everything is one, everything is connected. Traditional Nuu-chah-nulth whalers would have known about the offshore mountains, he believes.

“I do really think that western science is starting to catch up to traditional knowledge,” Watts said.

Following the voyage, he gave a presentation to the Ha’wiih, the hereditary chiefs, prompting a discussion around Nuu-chah-nulth assertion of title to ensure proper stewardship.

“When I showed this, it really struck a chord,” Watts said. “I think the results are very concerning and very alarming, and I think we really do need to stand up for this area.”

Amplifying that message is important to Watts, whether that involves speaking or expressing ideas through his artwork.

‘Amazingly adaptive’

Due to the gravity of their research, the study’s authors wanted to get word out as soon as possible, Du Preez said. That’s why they wasted no time in presenting the paper to colleagues around the world.

“That’s probably the fastest way to get everybody on board,” she said.

Though troubled by the findings, Du Preez is encouraged, both by the “amazingly adaptive” life of seamounts and a move to ensure greater environmental protection. In 2017, DFO proposed a new marine protected area that would apply to 75 per cent of known seamounts off the B.C. coast and all that are shallow enough to be disturbed by human activity. As well, the status would protect all known hydrothermal vent fields.

The goal is to have a marine protected area established by next year, although progress has been slowed by the COVID-19 pandemic. That promises long-term safeguards from oil and gas activity, mining, dumping and bottom trawling.

“We’re imploring them to mitigate every known impact there is. I’m hoping these animals are going to survive down there,” said Du Preez.

There is a broader message that scientists also hope to convey: that seamounts serve as an environmental warning, a barometer for human impacts where they might be least expected.

“The co-authors very much look at this paper as a case of the canary in the coal mine,” Du Preez cautioned. “We were able to collect data to show what’s going on here, but that’s not the case in other parts of the world.”