Amid a season of escalating COVID-19 cases across the country, a positive announcement from Ottawa surprised the country Monday morning. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced that vaccines for the respiratory disease could be in Canada as early as next week, due to an agreement secured with the American drug company Pfizer.

Arrival of the 249,000 doses of the vaccine are contingent on approval from Health Canada, which is expected in the next few days, and millions of more are due to arrive in January. Two doses must be given to a person for the shot to have its 95 per cent effectiveness rate of warding off COVID-19, according to Pfizer’s clinical trials.

This announcement accelerates a distribution plan previously announced from Ottawa, which would have put Canada a month behind some other first-world countries in the race to break the spread of COVID-19 through mass-inoculation.

But although Indigenous communities have been identified as a priority group for vaccination, initial details of the campaign indicate that it will be several weeks before doses come to remote Nuu-chah-nulth communities. The Pfizer vaccine requires doses to be stored at -80 C, before vast quantities are administered within a short period of time.

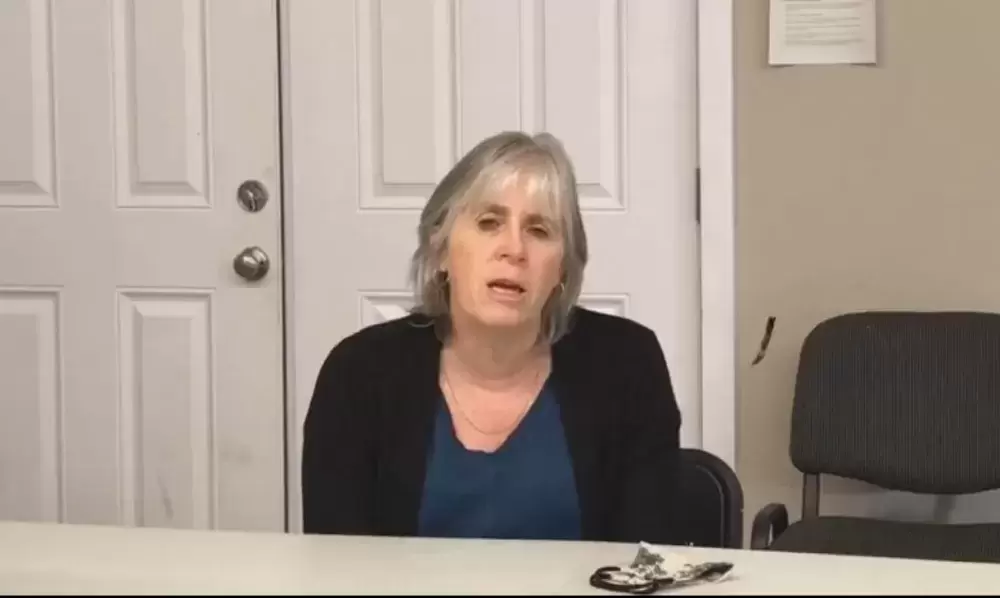

Before Trudeau’s announcement, Dr. Charmaine Enns, medical health officer for Island Health’s northern region, spoke about the Pfizer shot during the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council’s Annual General Meeting on Nov. 24. She said the first rounds of the vaccine will likely be given in large cities this winter.

“It’s very difficult for transporting because of cold chains, so most likely that vaccine will be dropped off in large centres - and once you open it, I think it’s almost about 1,000 doses that have to be given in three hours,” said Enns. “So that will go to large places, probably to health care workers. The next group that’s most likely going to be given preference will be long-term care facilities and residents in long-term care facilities.”

On Dec. 7 Trudeau stated that 14 sites across the country will be identified for the rollout, including two in British Columbia. As the bulk of B.C.’s COVID-19 cases have come from Lower Mainland and Fraser Valley, Enns expected that the initial distribution wouldn’t be anywhere near Nuu-chah-nulth territories.

“I can tell you if a vaccine came to British Columbia, we probably wouldn’t get it on the island,” she said. “It would go to the Lower Mainland and most specifically to Vancouver Coastal and Fraser Health because of the amount of activity there.”

“How would we bring all of our elders and vulnerable people to Vancouver?” asked NTC President Judith Sayers after Trudeau’s announcement. “I think we should be prioritizing people in remote communities who don’t have easy access to hospitals.”

Meanwhile, Ehatis continues to be the hardest hit remote settlement on the west coast of Vancouver Island. With 22 confirmed cases as of Dec. 6, one fifth of the Ehattesaht Chinehkint’s on-reserve population has become infected, although 11 of the 22 reported cases have recovered and the First Nation has yet to report any hospitalizations.

“After some success in our community, the virus is making another attack on our families,” read Councillor Ashley John during a Facebook announcement from Ehattesaht’s elected chief and council on Dec. 6. “Some people have chosen to disregard these measures.”

Following two weeks under lockdown, the First Nation announced more stringent rules on Dec. 6 with the Infectious Disease Bylaw. This brings tickets and the withdrawal of membership supports for those found to be breaking the lockdown orders of hosting gatherings or having any visitors in one’s household. Ehatis residents are also required to wear a mask if outside of their home, and must apply to the First Nation three days in advance for approval to leave the reserve. Even travel for medical appointments has been suspended, and gatekeepers will deny entry without approval from the nation’s government.

Other vaccines have come before health Canada that could better suit distribution in small, remote communities. The federal government has made purchase agreements with Massachusetts-based Moderna, which can be kept at fridge temperatures for up to a month before being administered.