A 50-year-old shipwreck leaking diesel and oil in Nootka Sound lies more than 100 metres down, an extra challenge for a spill response working to limit environmental damage.

Fuel bubbling from the wreck of the Schiedyk, an 8,700-tonne Holland America freighter that hit a reef off Bligh Island on Jan. 3, 1968, has increased in recent weeks, threatening shoreline and wildlife.

A co-ordinated response, including containment and cleanup efforts, is underway three months after reports in mid-September of an oily sheen on Zuciarte Channel near the east end of Bligh Island, a marine provincial park in Mowachaht/Muchalaht territory.

“We have a pretty good idea of what we’re up against,” said Tyler Yager, Canadian Coast Guard incident commander. “It’s something we’re taking very seriously. There is no indication the upwelling is going to stop any time soon.”

To the contrary, the spill is growing and spreading.

“I think, from everything I’ve heard, that it’s really picked up in the last month,” Yager said.

Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation (MMFN) and Hesquiaht First Nation are part of a unified command post to manage the response and environmental cleanup.

MMFN Chief Jerry Jack said they weren’t aware of the extent of the problem until a helicopter pilot captured aerial images of an oily sheen. Jack was planning to tour the site Wednesday, Dec. 16.

“The biggest concern is whether the oil is contaminating our water and shoreline and animals if any,” he said.

Using a remote operated underwater vehicle (ROV), they didn’t have difficulty connecting the sheen to its source, Schiedyk, roughly 115 metres (360-400 feet) down.

“We did send an ROV down,” Yager said. “We’ve been able to determine significant damage to the ship, either from the grounding or tumbling off the reef.”

A remotely operated camera revealed heavy oil leaking from the hull. A lab test provided another clue critical to cleanup: bunker fuel.

“That gives us a better idea because, first of all, it confirms the source,” Yager said. “It also gives us a better idea of what we’re looking at moving forward.”

A team of about 40 personnel is working on site while another 43 staff lend support at various other locations in what amounts to a “virtual command post.” Along with the coast guard, federal and provincial environment ministry staff and Western Canada Marine Response Corporation are involved.

As a pandemic precaution, NTC requested that unified command limit its on-site team and stay clear of Friendly Cove.

Yager, who has handled similar spills in recent years, was still gathering facts Monday and wasn’t sure how long cleanup might take.

“Too soon to say,” he said. “This isn’t going to be a quick fix. We’re going to be here for some time. Right now, we’re very much in a response mode.”

A slow but continuous discharge of fuel drifts from the wreck. Six marine pollution response vessels are working in the channel and two more were expected within days. Three animals — two sea otters and a great blue heron — have so far been linked to the spill. One otter died, but this animal was not "oiled", according to Bligh Island Shipwreck response.

Yager could recall only two similar incidents over the past decade. In 2013, the coast guard responded to fuel from General M.G Zalinski, a U.S. Army transport ship that sank in Grenville Channel off Prince Rupert in 1946. There was less fuel involved in that incident and the wreck was 30 metres down. Schiedyk lies three to four times deeper, close to or beyond the maximum depth for divers.

“It’s the deepest,” Yager said. “They all have their own complications, but this is the deepest. It may have to be the ROV that responds.”

Drone footage captured last week showed fuel spreading along the shoreline. Crews are recovering the contaminant as it floats to the surface, using a tandem sweep with a curtain boom and absorbent boom suspended between two vessels. Another oil recovery vessel will capture fuel spread by ocean current. Aerial reconnaissance and marker buoys are charting ocean current flows and help with spill projection modelling.

The information gathered should help direct response measures, allowing teams to deploy booms so that ecologically and culturally sensitive areas can be protected. Seven sensitive sites have so far been identified.

Jack said he was at a Gold River restaurant Sunday when one MMFN member mentioned that he helped load the Schiedyk at the Tahsis pulp mill the night of the sinking. With two experienced pilots in charge, the ship headed down Muchalat Inlet in calm seas before grounding two hours later.

Roy Williams was living in nearby Yuquot when he and his family learned of the rescue that night.

“We heard it over our CB,” Williams recalled.

With his brother-in-law, Williams crossed the sound in a small boat. They stood by, watching within 50 metres of the badly listing freighter.

“When we saw the ship, there were three master tugs trying to keep it upright,” he said.

The last attempt to save the Schiedyk failed and the ship slid off the reef the next day.

Capt. Arie Van Dijik told a Times Colonist reporter the ship sailed too close to the island and they tried to correct course.

“We saw the shoreline coming,” the skipper said. “We had lots of warning. We knew what was going to happen if we didn’t change course, but the ship simply didn’t turn.”

He blamed poorly loaded cargo for the collision, but no cause was officially determined.

Help soon arrived. RCMP vessel Tahsis was there in two hours while the icebreaker Camsell was diverted, arriving four hours later to pick up crew. Three tugs were dispatched from Victoria. A coast guard cutter and small tugs stood by ready to assist.

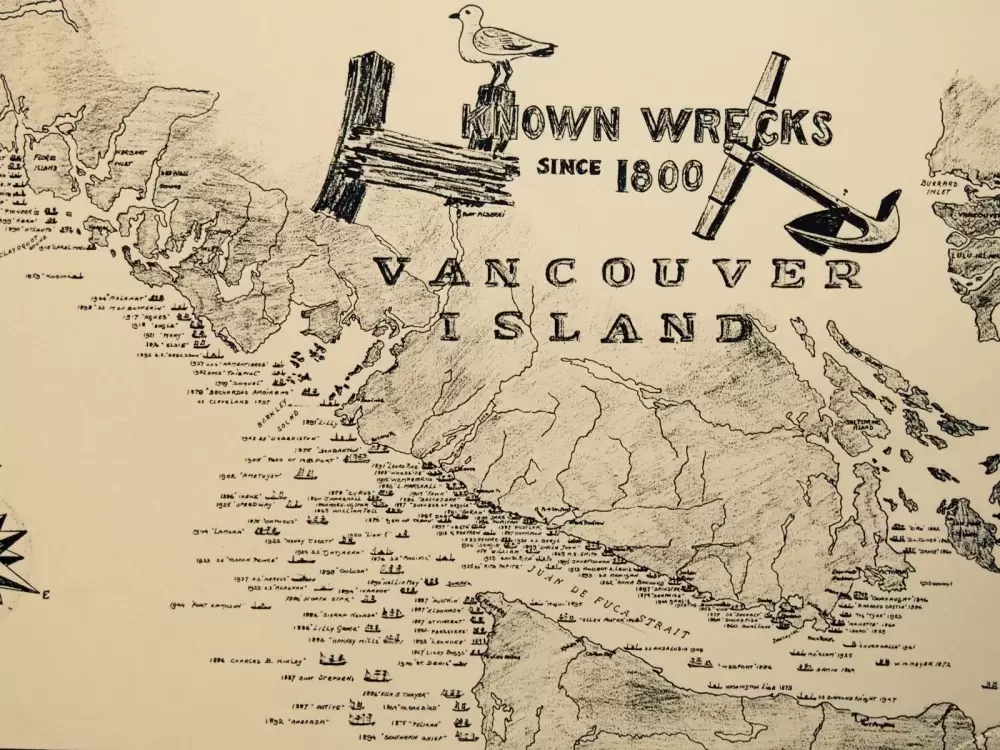

Historic shipwrecks are common on the Island’s west coast. From Cape Scott to Tillamook Bay in Washington State, the region is known as the Graveyard of the Pacific, littered with dozens of wreck sites. Jack wants to see similar hazards identified.

“I’m hoping they will be doing some investigating,” he said. “I would imagine that back in the 1950s and ’60s they weren’t as concerned about the environment as we are now.”

Schiedyk’s owner, Holland America, was later bought out by Carnival Corporation, headquartered in Seattle. Insurer Lloyds of London wrote off the wreck in 1968 and paid out the value of ship and cargo to Holland America.