A call for urgent reforms in logging practices to protect B.C. communities from climate change impacts reflects what First Nations have known all along, says NTC President Judith Sayers.

“There is so much at stake,” Sayers said after speaking out on the issue, publicly backing a Sierra Club report released Feb. 1. “I’m hoping people wake up. The forest fires two summers ago in British Columbia were just devastating.”

Intact Forests, Safe Communities, commissioned by Sierra Club B.C. and written by forest consultant Peter Wood, points to a glaring omission from B.C.’s Climate Risk Assessment: a failure to account for logging impacts.

Wood contends industrial logging can have a major effect on frequency and severity of climate-related risks such as floods, landslides and wildfire.

“If the B.C. government is serious about reducing the risk to human health and safety posed by climate change, current forest practices will have to be fundamentally changed,” he concludes.

Wood endorses recommendations of the province’s Old Growth Strategic Review, completed six months ago: “It is now a matter of implementing them.”

According to the review, much of B.C.’s old growth strategy was either disregarded or never implemented after it was developed 30 years ago.

“Had that strategy been fully implemented, we would likely not be facing the challenges around old growth to the extent we are today,” wrote foresters Al Gorley and Garry Merkel.

The review points to “a recognition that society is undergoing a paradigm shift in its relationship with the environment, and the way we manage our old forests needs to adapt accordingly.”

B.C. Forestry Alliance, a group of forest industry workers and supporters on the Island, sees it differently. The alliance formed two years ago in Campbell River out of frustration during a lengthy labour dispute.

“There has to be a balance and what they’re asking for is not a balance,” said Carl Sweet, alliance spokesman. He maintains that old growth is already well protected and thinks the province has already gone too far in shrinking the harvestable land base: “When does it stop?”

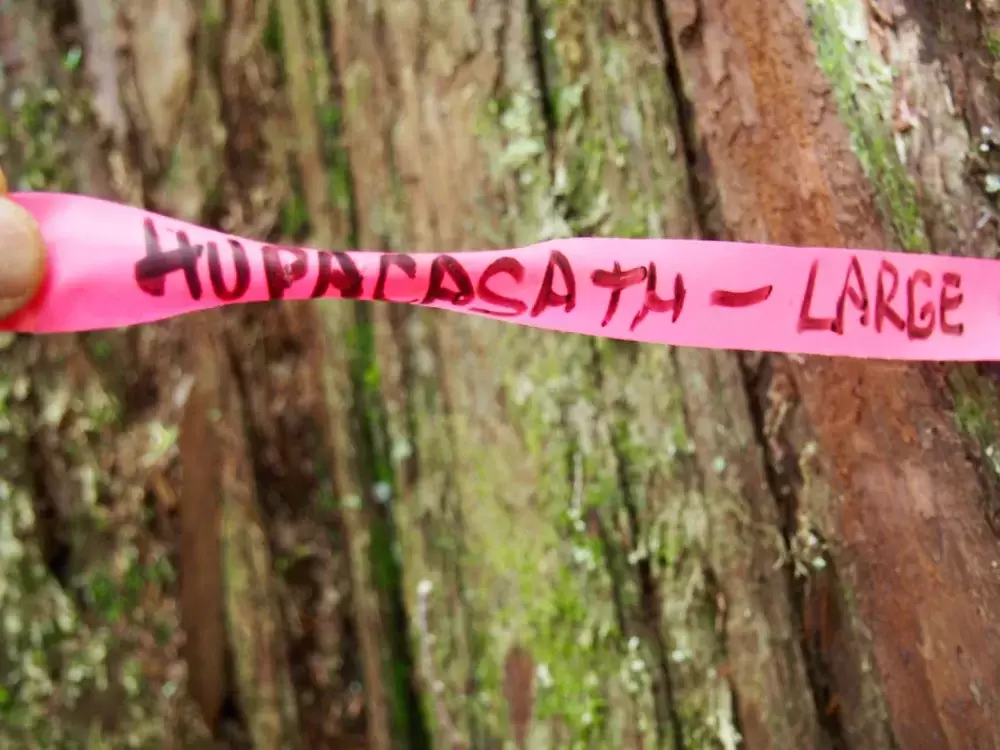

During the 2020 election, Premier John Horgan committed to full implementation of the old growth review recommendations. As an initial step, the province deferred old growth logging for two years in nine areas totalling 350,000 hectares, including Clayoquot Sound.

Scientists, foresters and environmental groups maintain the actual amount of old forest protected amounts to a small fraction of that. Meanwhile, second-growth logging continues in those areas.

Echoing the strategic review, the Sierra Club report calls on the province to engage Indigenous decisionmakers in a government-to-government process and to revise all forest legislation in accordance with the Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (DRIPA). The declaration obligates governments to respect and support Indigenous management of forests within their territories.

“First Nations have long been lobbying the B.C. government to recognize their right to manage the forest in their territories and to protect their sacred sites, old-growth ecosystems that support medicinal plants, and habitat for wildlife and birds,” Sayers said. “Through management of their forests, they would keep healthy forests with high environmental standards.”

The NDP government has continued the same approach to forest practices as its Liberal predecessors, Sayers said, citing as an example the logging of old growth in the Nahmint Valley. She sees need for a more ecologically and culturally considered approach, with greater protection of watersheds for salmon habitat and drinking water.

“As Nuu-chah-nulth people we have watched forestry activities in our communities and we’ve been very dissatisfied,” she said.

Forest-managed “salmon parks” — proposed by Mowachaht/Muchalaht, Ehattesaht/Chinehkint and Nuchatlaht First Nations — offer an alternative approach, she said.

“Climate change is very real and we are living with the impacts of it now and one of the ways to deal with it, to try to mitigate it, is through forest management,” Sayers said. “With drier summers, there is less water or no water in some streams. We’ve got to protect what we have now.”

The proportion of B.C. forests that remain intact and the diversity of forest types are key factors in mitigating impacts of a warming climate, yet time is running out, according to the Sierra Club report.

“There are, however, limits to mitigating climate risks, and unless greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) are not reduced to net zero globally in the near future, it will be nearly impossible to prevent catastrophic impacts to forests,” Wood writes. “Around the world, scientists are already witnessing widespread climate-induced forest die-off, creating a dangerous carbon cycle feedback, both by releasing large amounts of stored carbon and by reducing the extent of the future forest carbon sink.”

Sweet defends the industry and the jobs it brings to rural communities, First Nations among them. He doesn’t agree with the science behind the report, either.

“I think forestry workers are playing a role in carbon sequestration,” Sweet said. Converting forests into wood products is a means of locking up carbon rather than having it enter the atmosphere as carbon dioxide, he said.

The BCFA has led a letter and texting campaign directed at Horgan, opposing any reduction of the harvestable land base while also calling for “substantive dialogue with First Nations working towards forestry-based stability for their communities.”

Sweet concedes changes in forest practices are needed, but believes the industry is keeping pace with climate change.

“They want to ensure they don’t overcut,” he said. “They only harvest one-third of one percent a year. As we reduce the harvestable land base, we will concentrate harvesting on smaller and smaller areas. They can harvest larger areas less frequently.”

Sayers believes there is a need to keep pushing government on the most pressing issues, such as forest management reform, even as COVID-19 continues to dominate public attention. Implementation of DRIPA, adopted by the province over a year ago, is another example, a source of continued frustration.

“What changes have we seen? The premier says they’re waiting for an action plan. I’m waiting for serious discussions in each of the sectors on how we change this,” she said.