Lucy Sager grew up along the Highway of Tears in Terrace. The 725-kilometre corridor of highway in British Columbia has been the location of many missing and murdered Indigenous women (MMIW).

Driven by a range of factors, including colonization, the disproportionately high number of MMIW is, in part, a result of poverty. Without a driver’s license or access to a vehicle, many First Nations are forced to hitchhike, she said.

“The cost of hitchhiking can be your life,” said Sager. “And certainly, I’ve seen that.”

After high school, Sager went on to work in construction but struggled to hire First Nations in the surrounding communities.

“I would ask chief and council in multiple territories, ‘what is the biggest challenge for your people going to work?’” she said. “And consistently – for five years – it was driver’s licenses.”

The insight prompted Sager to return to school to become a driving instructor and launch the All Nations Driving Academy, which delivers driving courses through an Indigenous lens.

“I did this with the intention to support nations to have their own driving schools,” she said. “I was finding that in Indigenous communities [across B.C.] only five to 25 per cent of people have a valid driver's license.”

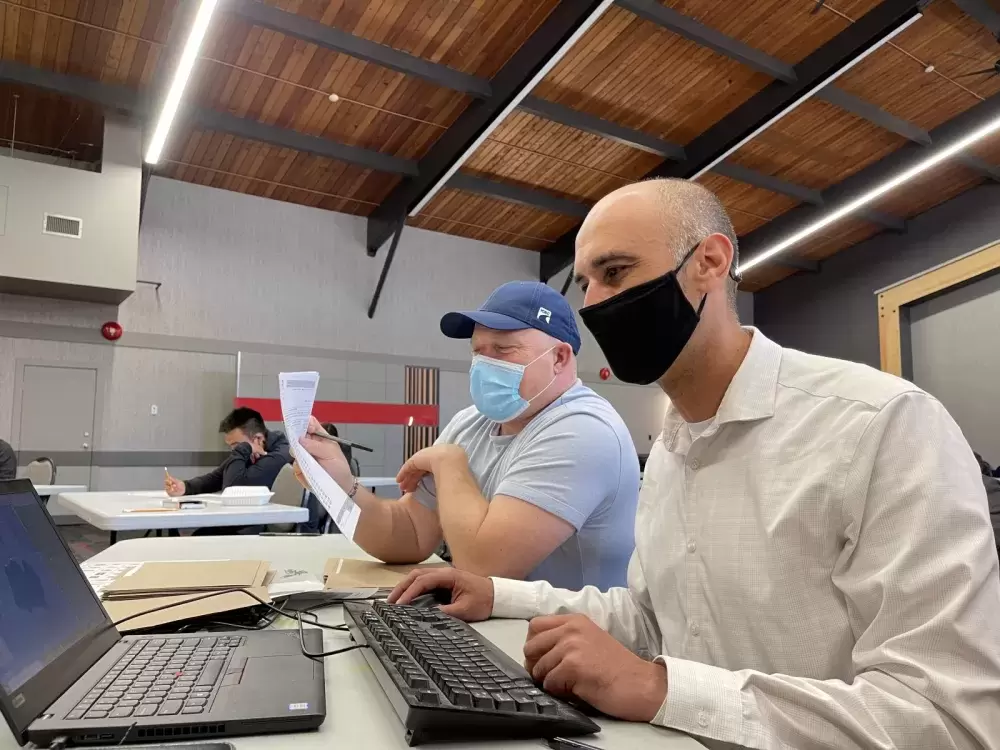

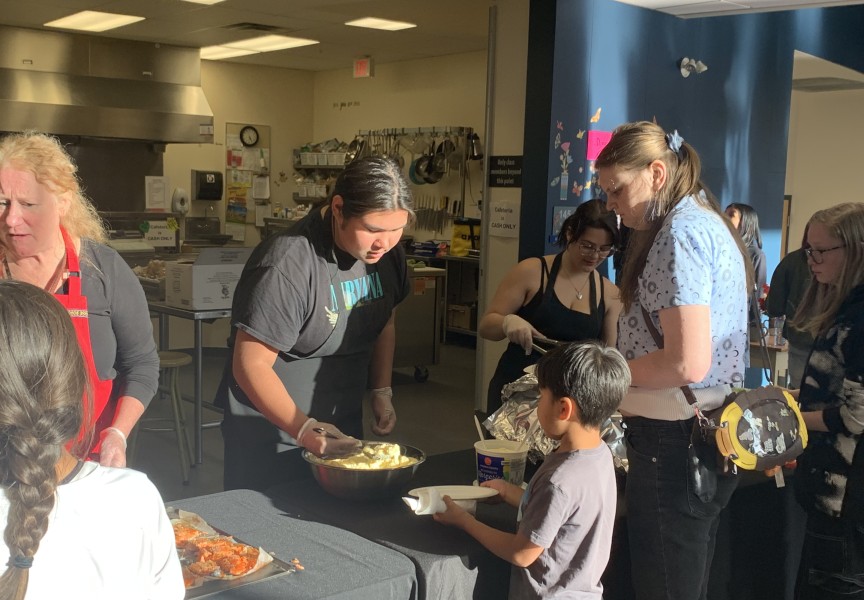

In coordination with Hayden Seitcher of the Tla-o-qui-aht youth warriors, Iris Frank, Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation education manager, and ICBC, Sager hosted a two-week driver training session at the Best Western Plus Tin Wis Resort in Tofino.

“In community, a lot of the parents don’t have a car of their own,” said Seitcher. “So when [training] like this comes to where you are, it helps a lot … especially with the L [license] because it’s another incentive to start studying.”

Bringing services like driver training to First Nations communities helps “remove barriers” for Nuu-chah-nulth people, said Frank.

If you are caught driving without a license in B.C., you face a fine between $500 and $2,000. A court may also sentence you to six months in jail. If you are caught driving while prohibited a second time, you face a similar fine and a court might sentence you up to one year in jail.

“If you go to jail, then you have a criminal record,” said Sager. “And if you have children, your kids go into care. It’s actually super serious.”

For many coastal communities, not only is travelling to Port Alberni for driving lessons logistically difficult, it is financially inaccessible, said Frank.

“All services don't stop in Port Alberni,” she said.

Through funding from ICBC and Chee Mamuk, an Indigenous program run through the BC Centre of Disease Control, 21 participants from Ka:’yu:’k't'h'/Che:k:tles7et'h', Ahousaht, Tla-o-qui-aht, Huu-ay-aht and Ucluelet First Nations received Class 7L and Class 4 Student Courses for free.

Since launching the All Nations Driving Academy over three years ago, Sager has continued to mobilize her efforts by studying a doctorate in social sciences to determine the impact of colonization on driver's licensing for Indigenous people in Canada.

Research on the topic has been studied in New Zealand and Australia, but never in Canada, she said.

For some, their first experience in a car was when they were being driven away to residential school, explained Sager.

“There’s a lot of trauma around the car,” she said.

The rates of death, hospital admission and injury related to motor vehicle collisions are twice as high among Indigenous populations than the general Canadian population, according to a 2013 study published in the Canadian Journal of Rural Medicine.

Between 1992 and 2006, motor vehicle collisions were the leading cause of death for Indigenous children aged 1 to 4 years old. With a rate of 5.6 per 100,000, it was nearly four times higher than the rate for other B.C. children, according to the 2016 report Where the Rubber Meets the Road: Reducing the Impact of Motor Vehicle Crashes on Health and Well-being in BC.

Through exposure therapy, Sager said she hopes to create positive memories for First Nations people so they feel safe in a vehicle.

“I want people to feel like they’re safe to move their life forward,” she said. “There’s so many incredible stories like mothers getting reunited with their children and people who have chosen a life of sobriety because now they can be a legal, compliant driver and get a job.”

Frank said she hopes the nation continues with the pilot project after debriefing with Seitcher and Sager to determine how they can improve it for Nuu-chah-nulth members going forward.

Not only do the courses provide members living in Ty-Histanis or Esowista the ability to complete simple daily duties, such as checking their mail in nearby towns, it gives them another skill set to add to their resume, said Frank.

“When people get a driver's license [they’re] challenging systems,” said Sager. “We're challenging systems of policing – like justice, corrections and health, because there's this whole conversation around social mobility. When people start to rise, we're disrupting how people are also kept down. And I will say it's rocking the boat, and I think it's rocking it in a really good way.”