After six months of all-out efforts to recover bulk oil and diesel seeping from a sunken freighter in Nootka Sound, officials were surprised by how little fuel remains on the bottom.

“I think the biggest surprise was the lack of oil down there,” said Coast Guard Unified Commander Paul Barrett, remarking on a technical assessment that found 147 cubic metres (147,000 litres) of fuel remains in two tanks aboard the MV Schiedyk.

That is roughly the equivalent of three mid-sized swimming pools filled with petroleum, all of which has to be safely removed to remediate the hazardous wreck.

The Holland America freighter struck a reef in 1968 after leaving Gold River. Fifty-two years later, the sunken wreck began “burping” fuel, first reported as surface sheening last fall. Initially, spill response officials were concerned it might still hold most of its fuel supply, estimated at 600 tonnes.

“You would expect to see reports about more black oil on the surface and we didn’t see it,” Barrett said.

Earlier in June, DFO/Canadian Coast Guard awarded a $5.7-million emergency contract to U.S. salvage firm Resolve Marine Group, the same company contracted to do the assessment, to remove remaining fuel from the wreck using a process called “hot tapping.”

Offshore supply ship Atlantic Condor returns to the Bligh Island wreck site over the weekend to begin the operation, the critical next phase of a challenging deep-water spill response.

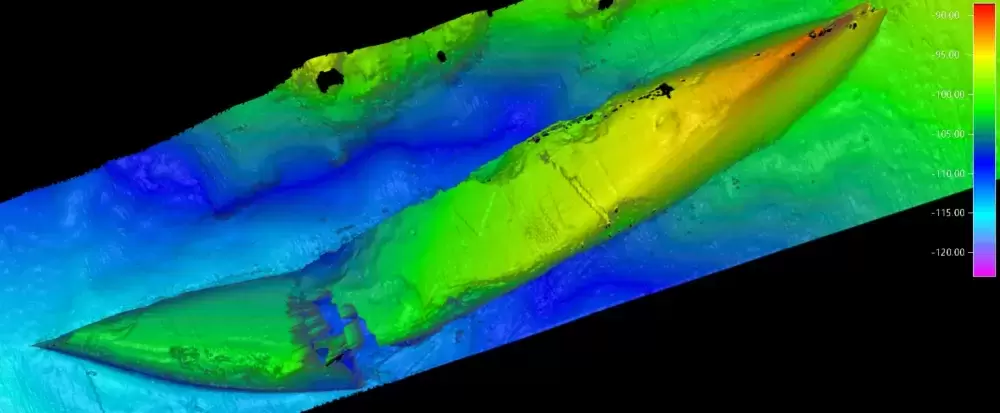

What has made the operation particularly challenging is not only the depth (106 to 122 metres, too deep for divers), but its remote location in combination with the elements and pandemic safety provisions. Bulk fuel removal is no less complicated. The operation is expected to take a couple of weeks or more, depending on weather conditions.

Hot tapping is considered a lower-risk method of fuel removal. The process involves drilling holes in the fuel tanks, attaching a drainage valve and pumping fuel through a hose connected to a support vessel on the surface. Salvage operations have used the method on shipwrecks for years, including the Manolis L in Atlantic Canada three years ago.

Sonar imagery and other data captured during the technical assessment have indicated the operation has several advantages working in its favour.

Originally, the wreck rested in relatively shallow water about 33 metres down. About a decade ago, it slid further down the reef and appears to have rolled upside down at the bottom, Barrett explained.

“That is really beneficial to us, to be honest,” he said. “The tanks are all flat-bottom tanks,” making fuel removal simpler. Really, in as far as an attitude to have, this is the perfect one.”

Schiedyk’s hull was found to be 16-18 millimetres thick, considered strong enough to withstand the fuel removal operation.

“She’s still got 80 percent of her hull plating thickness now,” Barrett said. “We don’t have to worry about the thing collapsing.”

Using a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) from Eastern Canada, Resolve Marine succeeded in temporarily patching fuel leaks earlier this spring using rubber “submar” mats and rare earth magnets. Despite this, some fuel continues to seep from the wreck.

The ROV will be heading back down to the wreck this month to drill the tanks and secure pumping equipment. Hot water is then pumped from Atlantic Condor into the tanks so that fuel flows more readily. Once the mixture is aboard the Condor, fuel and water will be separated. Fuel is then stored for safe disposal and water is reused in the operation. Diesel is lighter than oil and will not require the same process.

There is a slight risk of a larger release of fuel during this phase of the response, the Coast Guard warns. To manage the risks, they have designed redundancies within the system, maintaining backup resources such as containment booming, skimmers, vessels and barges for possible deployment. They have on hand 125 per cent of the fuel storage capacity required for the project in case there is more in vessel than what the surveys indicate.

They are also undergoing a surge in personnel for this phase of operations with 120 on site during this stage of operations. Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation will be actively monitoring the operation and area while Focus Wildlife observers and a DFO marine mammal team will be on the water. Sonic deterrents will keep birdlife away during the operation.

“It’s time to get this done,” Barrett said.

June is one of only two windows of opportunity identified by the technical assessment, so timing couldn’t be better, he noted.

After fuel is removed, Coast Guard hands off responsibility for the response to its partners, including Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation, DFO and the provincial government. Monitoring and tracking of the site will continue for months afterward.

“It can be tricky, no doubt about it,” Barrett added. “We want everybody to be comfortable with the end point.”

Despite the expense of spill response, maritime law appears to offer faint hope of recovering costs. According to a Coast Guard summary of the Manolis L. spill response — a similar operation that cost the Canadian government $15 million to remediate in 2018 — cost recovery has a five-year time limit under the Marine Liability Act. That’s five years from the date of sinking.

Barrett cited a 2005 survey by the International Oil Spill Conference that estimated there are about 8,000 shipwrecks worldwide containing anywhere from 2.4 million to 20.5 million tonnes of fuel.