Nootka Sound, BC - With oil now removed from the MV Schiedyk, the remediation effort around the 52-year-old shipwreck now turns to examining aquatic life in the area.

On Monday, July 12 Fisheries and Oceans Canada reported that the underwater pumping of bulk oil and diesel from the vessel was completed by the end of June. Over the span of two weeks, 60 tonnes of heavy oil and diesel was removed from the Schiedyk, which lies 120 metres underwater by Bligh Island in Nootka Sound. Another 48,511 kilograms of oil and oily waste was recovered from the surrounding environment since the leak was first detected by a Fisheries and Oceans Canada surveillance flight early December.

It took over half a century for a consistent stream of oil sheen to be noticeable above the shipwreck, which sank on Jan. 3, 1968 when the vessel hit a reef after leaving Gold River. Loaded with approximately 1,000 imperial tons of grain and pulp, the ship originally sank 33 metres down on the south side of Bligh Island, which is east of Nootka Island. Then approximately a decade ago the vessel slid further down the reef, rolling upside down to rest east of Bligh Island, according to a technical assessment conducted during the recent recovery effort.

Chief Jerry Jack of the local Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation said the oil leak was unexpected.

“It was a surprise for us for it to start leaking,” he said. “I lived here in ’68 and I don’t even recall my dad talking about a shipwreck that happened at Bligh Island.”

Under the coordination of the Canadian Coast Guard, the seven-month containment and recovery effort involved multiple government departments and private companies, with federal, provincial and First Nation incident commands.

“We set out directives for what the operation was going to do every day,” said Jack, who serves as incident commander for the Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation. “My assessment is that everything went well. The Coast Guard couldn’t do any more.”

It’s unknown how much oil has leaked from the shipwreck since it sank in 1968, said Greg Walker, the effort’s federal incident commander, although a noticeably consistent stream was wasn’t detected until recently.

“With the anecdotal information we have, every once in a while there were some small releases that were reported,” he said. “It wasn’t until December that we started to see a larger amount of release of upwelling on the surface…we went back and discovered the actual wreck itself.”

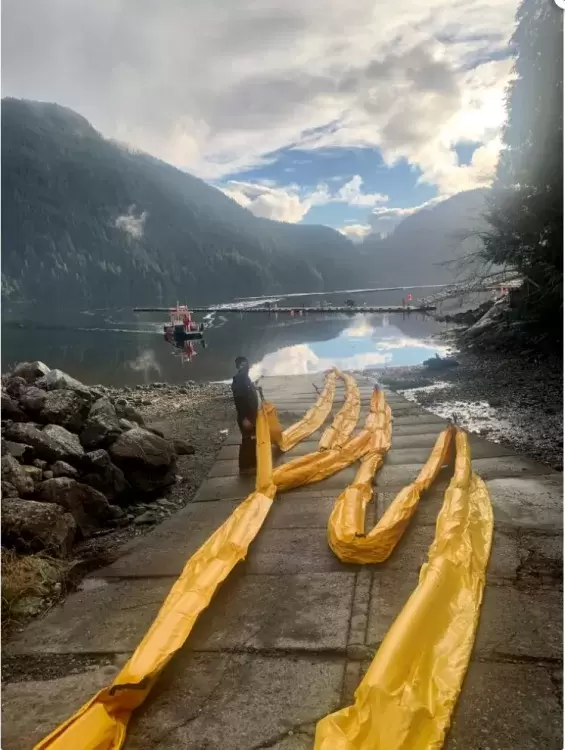

Booms were quickly spread to contain the oily sheen as the departments involved determined how to stop the slow leak. In the spring holes in four fuel tanks were patched with rubber mats and magnets. With drainage valves and hoses secured to the tanks, in June hot water was injected to liquefy the heavy oil and allow it to be pumped to the coast guard’s Atlantic Condor ship on the surface. Oil was then removed from the water and taken to a regulated disposal facility.

Jack said that this process was closely watched for environmental impacts.

“Environment Canada would put recommendations to the Coast Guard on what to do,” he said. “They had these models of if there was a catastrophic release.”

At a depth too deep for divers, the underwater draining was performed by remotely operated vehicles under a $5.7-milion contract with the Resolve Marine Group. The Florida-based company was selected due to the specialized expertise needed to perform the underwater tapping, said Walker.

“We went out to look for a company that has a proven track record,” he said. “Resolve Marine Group was one of them.”

Now a team will be taking samples of fish, barnacles and other food sources in the area to detect any levels of heavy oil. So far the Coast Guard has identified just 23 animals affected by the leak, including a sea otter and various birds.

Fortunately, herring didn’t spread their eggs near the shipwreck this spring, said Walker.

“This year there was no spawning reported in Nootka Sound,” he said. “The spawning that was located was along the outside of the Hesquiaht Peninsula.”

Jack saw a minimal amount of oil spread beyond the vicinity of the shipwreck.

“There was very little oil on any rock or beach,” he said. “Between the contractors and the Coast Guard, they did a really good job.”

The types of fuel that leaked from the Schiedyk will react to the surrounding ocean in different ways, explained Walker.

“Diesel is highly processed, so it dissipates quite quickly and a lot of it evaporates,” he said, adding that the heavier fuel oil can evaporate as well. “It does also clump. Depending on how much is released, it will stick to the surrounding rocks and things like that. But over time waves break it down. It is kind of an organic matter, so other organisms do break it down.”

Sea life collected for sampling will be tested for toxins, with results going to government agencies.

“That information will go out to Health Canada,” said Walker. “They’ll make the recommendations and look at what that means for the populations that live in the area.”

Meanwhile it appears that the Schiedyk will remain on the ocean floor, as the 52-year-old shipwreck has become integrated into the natural environment.

“You probably couldn’t move it now because it’s deteriorated to such a state,” said Walker. “If you try and manipulate the hull too much it’s just going to break up and cause even more damage. A lot of the area now is likely a habitat for other animals that are down there.”