In the aftermath of an eight-day inquest into the death of Jocelyn George, a jury is calling for a systemic overhaul in how Indigenous youth are handled within the justice system, with recommendations for facilities that may have prevented the 18-year-old’s fate five years ago.

The coroners inquest wrapped up in late June, after a jury of five heard from dozens of witnesses at Port Alberni’s Capital Theatre – a few blocks away from where Jocelyn Nynah Marsha George was picked up by police on the morning of June 23, 2016. Found behaving erratically and delusional, the Hesquiaht mother of two was brought to the local RCMP detachment’s cells, where she remained for most of the day and the following night, until her condition had declined to the point where she was rushed to the West Coast General Hospital the following morning.

George was later airlifted to hospital in Victoria, where she died on the evening of June 24. Cause of death is listed as “drug induced myocarditis”, an inflammation of the heart muscle due to the “toxic effects of methamphetamine and cocaine”, according to the Coroners Service.

What happened from the time that George was found barefoot on the steps of a Salvation Army building until her demise the following day was put under a scrutinizing microscope during the inquest, with a stage full of lawyers representing the various agencies involved in her treatment, as well as counsel advocating for the inquest itself. The Coroners Act requires inquests for any deaths that occur while a person in the custody of a peace officer, and the proceedings are not to find fault but to present findings that prevent similar deaths in the future.

What has emerged from the process are 24 recommendations, led by several that indicate procedural failings in how intoxicated prisoners are managed.

Accounts suggest that George had not eaten for days by the time she was rushed to hospital, and the inquest jury recommended that the RCMP implement policies that ensure prisoners have access to water and food while in cells – and that the provision and acceptance of this nourishment be recorded.

“Reasons for withholding food or water should also be detailed in log book,” advised the jury.

Recommendations also include annual performance reviews, training and certification for municipal employees working as cell guards at the Port Alberni detachment.

George was still a minor while she was taken in the cell, but the inquest indicated there may have been confusion about this among the various personnel overseeing her, leading to a recommendation for police training in legislative requirements for prisoners under 19. A release plan for the safety of minors is also in the jury’s list, as George was briefly removed from custody – barefoot with clothing still wet – for just over an hour the afternoon of June 23.

That afternoon police were called again due to George’s paranoid behaviour, and although she was assessed by paramedics, it was not deemed necessary to take the youth to hospital.

The fact that a jail cell appeared to be the best option for her led the inquest jury to recommend “a holistic wellness centre” in the Alberni-Clayoquot Regional District that offers a safe space for youth, with a sobering site and beds for those struggling with mental health issues and addictions.

“Right now there isn’t any place for an intoxicated youth in Port Alberni,” said Mariah Charleson, vice-president of the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, who gave her own recommendations during the inquest. “Unfortunately, if you’re an intoxicated youth right now in Port Alberni, you’ll get thrown into the drunk tank.”

To further strengthen the city’s support for young people, the jury wants to see a full-time social worker and youth advocate on the Port Alberni Indigenous Safety Team, as well as a crisis response team available nights and weekends.

The hope is that these measures might prevent other young people struggling with drugs avoid tragedy. But the jury sees the necessity of better advocacy for First Nations, a need that could be met through a justice centre in Nuu-chah-nulth territory.

In March 2020 the province and First Nations Justice Council unveiled a plan for the legal system to better serve Indigenous people, including the establishment of 15 justice centres in different parts of B.C. Charleson sees the inquest recommendations as another reason for one of these facilities to be set up to attend to the overrepresentation of Nuu-chah-nulth people who are incarcerated.

“It’s a massive gap, so it would be a start to the many, many justice-related issues that we have here,” she said. “That wasn’t her first time being incarcerated, what were her options?”

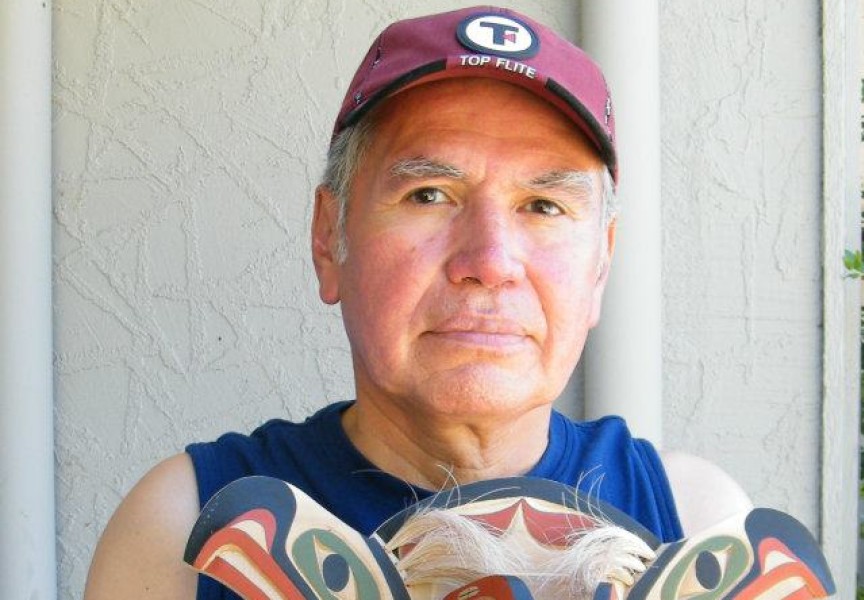

George’s family sat through the eight-day inquest, holding a large picture of the 18-year-old. On the first day of proceedings her uncle Matthew Lucas told the inquest how he will remember his niece.

“She had dreams of where she wanted her path to go, she wanted to have her own house, she wanted to have a good job,” he recalled. “She was an avid dancer, she loved to dance traditionally for her grandfather. All of her regalia she made herself and she treasured it, she took pride in everything she wore when she was dancing.”