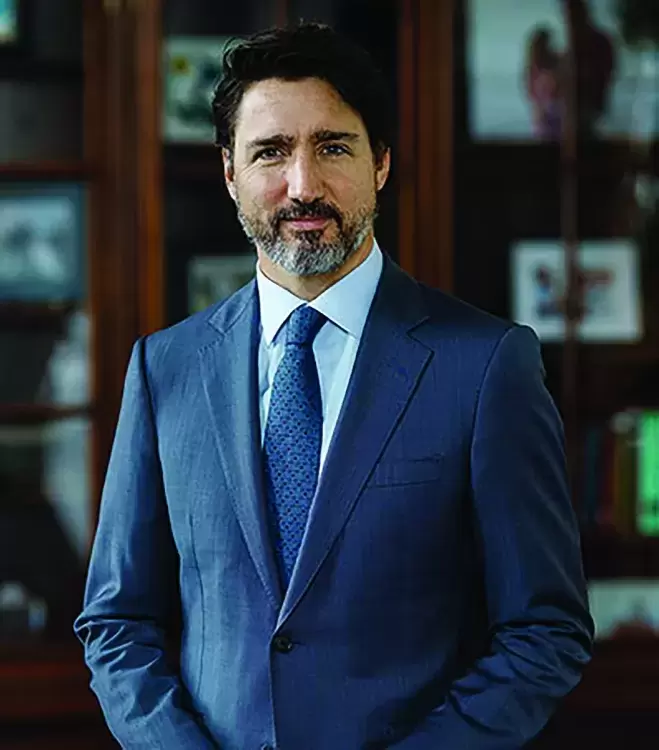

Another election season is underway, after a mid-August announcement from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau that Canadians will head to the polls on Sept. 20 – less than two years since the last federal election took place.

By calling the election the Liberals seek to reclaim the majority government they lost in 2019, due in large part to surging support for the Conservatives led by Andrew Scheer. Now the biggest threat to Trudeau’s hopes of a majority lie in how the Conservatives, under new leader Erin O’Toole, can attract voters. When Parliament was dissolved the Liberals had 155 seats, while the Conservatives held 119, followed by the Bloc Québecois’ 32 and the NDP’s 24. On the outskirts sat five independent MPs and 2 Green Party representatives.

But in Nuu-chah-nulth territory on the west coast of Vancouver Island federal representation has gone to the NDP over the last few elections. Since 2015 the three ridings that cover the home territories of Nuu-chah-nulth nations, North Island-Powell River, Mid-Island and Cowichan-Malahat-Langford, have gone orange. Now all three of these respective incumbents, Rachel Blaney, Gord Johns and Alistair MacGregor, seek re-election, after all of Vancouver Island went NDP in 2019 except two ridings in Nanaimo and Victoria’s Saanich area, which were claimed by the Greens.

Data collected from some individual polls in 2019 show an overwhelming support for the NDP in communities with a high proportion of Nuu-chah-nulth voters. In Ahousaht 164 of the total 175 votes counted on election day were for Gord Johns, while Rachel Blaney took 66 of the 83 ballots collected in Kyuquot.

Such strong support in remote communities comes down to how effectively a candidate can maintain relationships, said Alexander Netherton, a professor of Political Studies at Vancouver Island University.

“You’ll find political parties [that] really try to make ongoing relationships with Indigenous peoples,” he said. “The NDP is pretty good at that on this island, the Liberals on the island less so and the Conservatives don’t have a really great track record of that since the 1950s.”

Of foremost concern this election is how the government is going to manage contributing factors to global warming, said Judith Sayers, president of the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council. The situation so dire she doesn’t even refer to it as “climate change”, after heat records were broken in B.C. this summer while the province saw 860,800 hectares burned from over 1,500 wildfires – more than double the average area burned from over last decade of fire seasons.

“No. 1 priority for me is climate emergency. I think we’re far past climate change,” stressed Sayers. “Global warming has become an incredible issue for us, dealing with all these really high temperatures, forest fires, flooding.”

She noted some progress in the recent passing of the Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act, but this legislation has a goal of 2050 to bring greenhouse gases under control.

“It’s too far away and there are really no consequences in it,” said Sayers. “I think that the government has got to take immediate measures to deal with climate, because it’s impacting our lives, it’s impacting our sea resources, it’s impacting our housing, our health.”

Over Trudeau’s first term as Prime Minister he set up lofty expectations for First Nations, standing up in the house of Commons in 2017 to declare that no relationship was more important to Canada than that with Indigenous peoples. But over the following years frustration brewed among Nuu-chah-nulth people, particularly due to the failure of Fisheries and Oceans Canada to find agreeable terms with the nation’s negotiators. Talks between both sides have progressed little, despite multiple court rulings that upheld the rights of five Nuu-chah-nulth nations to catch and sell species from their home territories.

The issue escalated to a declaration in early August from the nations’ Ha’wiih, authorizing members to fish according to the First Nations’ own fisheries plans, not the allocations that were set by DFO.

“I have been continually shocked with the various allocations of fish species that the federal government has deemed appropriate. We have the inherent right to fish and sell fish in our traditional territories,” said Ahousaht Ha’wilth Hasheukumiss, Richard George, following the declaration. “Everything within our waterways is 100 per cent ours, and it is our right to continue our fishery. We are willing to share 50 per cent of our resources with the other user groups, but at the end of the day, the resources are ours to manage through our own conservation practices.”

“There’s seems to be a real push by the government to stop us from accessing our rights. I think it’s become a really big issue across the country,” noted Sayers. “We just met with the fisheries minister a few weeks back, and she had no commitment to Nuu-chah-nulth whatsoever. It was, ‘Well, I’m going to have to check with my staff on that’.”

But recent news from former residential school sites could force candidates to give more recognition to the concerns of First Nations. The discovery of 215 unmarked graves on the old grounds of the Kamloops Indian Residential School was the first of several to seize public attention this summer.

“These are universal injustices that we can all appreciate, and it makes, I think, Canadians feel uncomfortable, which it ought to,” said Netherton.

Although the existence of children’s remains at the former school sites was addressed years ago by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, it took the recent discoveries to force politicians to give the issue prominence.

“After the TRC there was a bit of movement but some kind of implicit denial,” said Netherton. “It’s as if the significance of that fact was kind of buried. Identifying these unmarked graves really, in my view, brings this notion of a cultural genocide right to our front door.”

Now candidates have less than a month to gain the trust of voters, but the decision among Nuu-chah-nulth people to engage in the election will depend on how they see their connection to the federal government, said Sayers.

“I think there’s two schools of thought. One is we’re a citizen of the Nuu-chah-nulth nation, we’re not a citizen of Canada, so I’m not going to vote and that’s their politics and not mine,” she commented. “Others are directly impacted by the federal government, whether it’s fisheries or justice or health, and they need to have a say in those things.”

“If we were going to poll Québécois, the majority would say. ‘I am more attached to Quebec than I am to Canada’, said Netherton. “The really interesting thing about living in a federation - and of course with treaty people - is that we can have multiple identities. The trick now is to be proud and to assert those identities.”