Canada’s newly appointed fisheries minister has inherited a formidable task on the west coast of Vancouver Island, where a contentious relationship with Nuu-chah-nulth has seen decades of litigation, stalled negotiations and a recent directive from hereditary chiefs for their people to fish according to the nations’ own plans.

Following this fall’s federal election that brought the Liberals back to a minority government, Vancouver-based MP Joyce Murray was appointed minster of Fisheries and Oceans in October. The federal ministry operates under the mandate of “sustainably managing fisheries and aquaculture,” while “working with fishers, coastal and Indigenous communities to enable their continued prosperity from fish and seafood.”

As Murray begins her new role, a cautionary letter was sent to her office on Nov. 10 from Judith Sayers, president of the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, and Cliff Atleo Sr., chair of the Council of Ha’wiih Forum on Fisheries, warning that scientific expertise will not be enough.

“The collapse of salmon stocks in recent decades is a challenge that your department cannot address on its own based on scientific knowledge,” reads the letter.

This would far exceed what the federal department allocated to the local First Nations earlier this year. Out of the 88,000 total allowable catch, 7,821 were set aside this spring for the five Nuu-chah-nulth nations that operate T’aaq-wiihak fisheries, with another 5,000 allocated for First Nations’ food social and ceremonial purposes and 3,441 chinook for nations in the Maa-nulth treaty. Meanwhile, the sports fishery was allocated 35,000 for the west coast of Vancouver Island, while the Area G commercial troll fleet got 36,738 before the chinook season opened.

Preliminary catch data had the five nations bringing in 10,734 chinook, while the recreation fishery was decreased to almost 23,000 and Area G brought in 25,225.

“We just haven’t been able to exercise our right,” said Sayers during the NTC’s Annual General Meeting in October.

“If you’ve ever talked to DFO, it’s like talking to the wall,” added Hesquiaht Chief Councillor Joshua Charleson during the meeting. “They come with an offer, they can’t deviate from this offer because they’re only mandated to give you what the minister has approved before the meeting. Negotiations have basically been stalemate since 2013.”

For over a decade, the right of Nuu-chah-nulth nations to commercially fish in their own territorial waters has been disputed in Canada’s courts. In a case involving the Ahousaht, Ehattesaht/Chinehkint, Hesquiaht, Mowachaht/Muchalaht and Tla-o-qui-aht First Nations, the B.C. Court of Appeal ruled in April that the five nations have the right to a fishery “of a moderate commercial scale”. This court decision removed the terms “small scale”, “artisanal” and “local” that were used in a prior judgement to define the scope of the nations’ fisheries.

Canada opted to not appeal that court decision, but T’aaq-wiihak’s share of chinook was only increased to 13,000. By August a directive came from the five nations’ Ha’wiih, informing their people to disregard DFO’s allocations in favour of the nations’ own fishing plans.

“We all went fishing. We sold under the authority of our Ha’wiih,” said Charleson, adding that DFO officers came to the docks once to harass the Nuu-chah-nulth fishers. “One of the Tla-o-qui-aht Ha’wiih…he told DFO officers to leave. They never came back, they respected his words.”

Following the Nuu-chah-nulth’s 50 per cent share of fisheries off Vancouver Island’s west coast, Charleson explained that in the future nations that are directly tied to the court case will be following their own Ha’wiih fishery management plans. The strategy will be for Ha’wiih to directly buy from their fishers, explained Charleson.

“The power of our fishery is Ha’wiih,” he said. “DFO can adjust their numbers accordingly to the rest of the sectors.”

During the AGM Tseshaht Chief Councillor Ken Watts noted that over the years the federal department has operated according to its own plans, regardless of what party holds power in Ottawa.

“DFO is its own machine of government,” he said. “It doesn’t matter who is in power, what mandate has been put forward, they’re going to do whatever they want in DFO.”

But part of Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s mandate is to “support Indigenous participation in fisheries,” a stake that ensures “continued prosperity”.

“There remains no more important relationship to me and to Canada than the one with Indigenous Peoples,” stated Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, in his supplementary mandate letter sent to former fisheries minister Bernadette Jordan in January. “You, and indeed all ministers, must continue to play a role in helping to advance self-determination, close socio-economic gaps and eliminate systemic barriers facing First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples. As minister, I expect you to work in full partnership with Indigenous Peoples and communities to advance meaningful reconciliation.”

“All of the DFO policies since the ‘60s and ’70s have been put in place to get the Indian out of the water,” said Charleson. “It’s gotten so bad now that we have four commercial fishermen in all of Nuu-chah-nulth who actually do it for a living.”

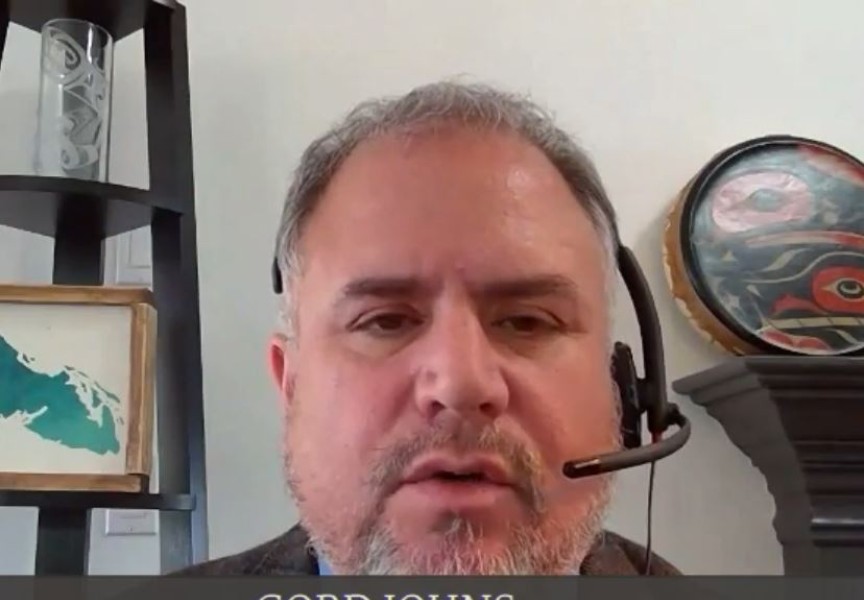

A new mandate letter from the prime minister has not yet been publicized, but a formal invitation for Murray to meet with the Council of Ha’wiih Forum on Fisheries is expected in the coming weeks as the minister settles into her new role.