B.C.’s Human rights commissioner is blaming “over-policing” for the grossly disproportionate number of Indigenous people caught up in the criminal justice system, calling for the redirection of funding from law enforcement to other social services.

This is one of several recommendations from Human Rights Commissioner Kasari Govender, who released a report on Wednesday, Nov. 24 that highlights discrimination against black and Indigenous people in B.C. Govender’s study was submitted to the Special Committee on Reforming the Police Act, a parliamentary group working on reassessing law enforcement in the province.

The recent report compiled a decade’s worth of arrest statistics from police departments in Vancouver, Surrey, Nelson, Prince George and Duncan, analysis that shows “significant racial disparities,” said Govender. From Jan. 1, 2011 to the end of 2020, Indigenous people in Vancouver were arrested at a rate ten times higher than white residents. Black people in Vancouver were arrested at a rate nearly five times that of white residents, while Asian and South Asians were less likely to have run ins with the police than other racial groups.

The report was accompanied by a study from Scot Wortley, a professor at the Centre for Criminology and Sociolegal Studies at the University of Toronto. He noted that in Vancouver Indigenous women are the third most likely group to be arrested, behind Aboriginal men and black males.

“Most studies across North America reveal that women, regardless of race, are significantly underrepresented in police statistics and charge recommendations,” said Wortley. “In British Columbia, however, Indigenous women appear to be an exception to that general rule.”

Enforcement of colonial law

Wortley pointed to three explanations for the unbalanced trends towards Indigenous and black people: racially biased policing, a prejudice among civilians who report crimes, or long-standing societal issues that contribute to offending.

“These higher rates of offending indeed may be related to issues of colonization, historical discrimination, multi-generational trauma and contemporary socio-economic disadvantage,” he said. “I think that these things, and how bias and discrimination in our history may impact the current criminological landscape, needs to be acknowledged, explored further and ultimately addressed.”

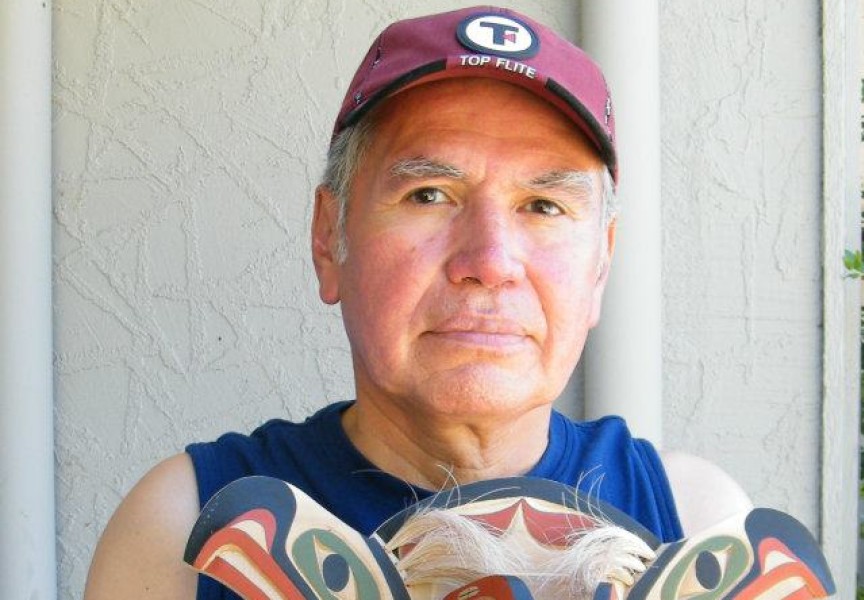

Boyd Peters is a director with the BC First Nations Justice Council who holds the policing and corrections portfolio. He said the human rights commissioner’s report confirmed what he has known for many years.

“Policing and the justice system in Canada have really failed our Indigenous peoples,” said Peters. “The outcomes of policing on us as First Nations people are really dire.”

Peters is Sts’ailes, a Coast Salish First Nation located east of the Lower Mainland, where he has seen his community’s distrust of law enforcement link back to when the RCMP enforced mandatory attendance at residential schools.

“That’s still instilled in us, and I’m sure that all of our First Nations communities have that kind of a feeling,” he said. “Even our community, to this day they don’t want to approach the police, they don’t want to report incidences, assaults or major crimes.”

Govender pointed to recent cases of Indigenous and black people being targeted during interactions with police, including the fatal shooting of Tla-o-qiu-aht member Chantel Moore in 2020. The young woman was killed on the porch of her apartment in Edmunston, New Brunswick, after an officer was called to check on her well being. Police accounts from the scene stated that Moore refused to drop a knife as she approached the male officer.

“People may wonder what over-policing looks like,” said Govender. “It looks like Chantel Moore, an Indigenous woman from B.C. who was shot and killed during a wellness check. These are the painful realities behind the numbers that we share today.”

Anti-bias training for officers

Wortley also pointed out that the number of charges against Indigenous people that ended up being tossed out of court was also particularly high.

“These were charges that were recommended by the police, but ultimately not pursued by the prosecution, or closed as a result of what was labelled ‘departmental discretion’,” he said. “Some might argue that this may represent lenient treatment of Indigenous and black people. Others, however, would argue that this may provide evidence of arrests of low quality or arrests that were based on limited evidence that had very little chance of prosecution if proceeded with.”

The Vancouver Police Department acknowledges the “implicit and explicit bias that effect decision making for everyone in society.”

“We have been proactive in helping our members identify and understand their own biases,” said the department’s media relations in an email to Ha-Shilth-Sa. “This includes ongoing anti-bias training for police officers, which begins during their recruit training and continues throughout their careers.”

The VPD also noted policy changes to how its members conduct street checks, resulting in a 94 per cent drop of these interactions in 2020.

“This was in response to community concerns that racialized people were overly represented in street check data,” wrote the police department.

But the ongoing mistrust of police remains an issue for Indigenous and black people, stressed Govender.

“When marginalized people cannot trust the police, they are less likely to report crimes against them,” she said. “To build this trust we need to reimagine the role of police in our province, including by shifting our focus from the police as default responders to other community safety strategies.”

Less police, more social services

This shift entails redirecting public funds that would otherwise go to police departments, “to invest in civilian-led services for people experiencing mental health and substance use crises, homelessness and other challenges,” stated the human rights commissioner’s report. The document added that some people’s needs “could be satisfied through increased social service provision, rather than a criminal justice response.”

Peters has seen the need for social services become more urgent in recent years with ongoing issues like the opioid crisis and mental health stressors that worsened during the pandemic.

“It’s out of control, so we really do need to put the person and the community at the centre,” he said. “So less police, more of those types of services and approaches. Community safety must be guided by and tailored towards the community needs.”

The human rights commissioner’s report also recommends removing police officers from schools, in favour of civilians with experience in counselling and coaching.

“Some of the tasks that fall within police right now are really better handled by community services, by health-based services,” said Govender. “That would be a much more effective way of addressing the health needs of our communities.”

“We’ve been pouring money into policing for decades now, with very little changing with respect to the level of crime and patterning of crime that we’re seeing in this data,” added Wortley.