After issuing Indian status cards for nearly three decades, Rosie Marsden moved on from her role this month, looking back on a term that saw registered members of the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council more than double.

There are now over 10,260 Nuu-chah-nulth people registered with the NTC, providing them status under Canada’s Indian Act, along with the rights, services and benefits that this entails. Many of these Nuu-chah-nulth-aht were registered by Rosie Marsden, who wrapped up her 29 years at the main NTC office in Port Alberni on Feb. 4.

When Marsden started her role as Indian registry administrator in December 1992 there were only about 4,000 registered people among the NTC’s 14 First Nations.

“It actually started off to be a one-year position,” she recalled. “The bands had thought that they were going to be taking over their own programs. One year led to another 28.”

Marsden had moved to Port Alberni in 1982, after growing up in the Gitxsan village of Gitanyow in northwestern B.C.

Over her years as the Indian registry administrator Marsden enjoyed seeing generations of Nuu-chah-nulth-aht pass through her office.

“I pretty much knew everybody,” she said. “Those that I registered earlier on, they were now having children and I was registering their children.”

Back in the early ‘90s registering for Indian status was less complicated, and didn’t even require photo identification. The status cards didn’t have expiry dates.

“Quite a few years back they didn’t have to produce any ID,” said Marsden. “But in the past 10-plus years they do have to produce picture ID and another piece of ID.”

Although requirements for status registration have become more extensive over the years, numbers steadily grew over Marsden’s term.

When she started the ramifications of Bill C-31 were still taking effect. In 1985 Parliament changed a discriminatory portion of the Indian Act, allowing the reinstatement for Indigenous women who had lost their status by marrying a non-status man. This also applied to children from these marriages, and led to over 114,000 Indigenous people across Canada gaining or regaining their status.

Then in late 2017 Bill S-3 came into effect, an amendment to the Indian Act aimed at addressing historic inequalities due to gender-based discrimination. This legislation applied to people who were without status due to their parents, grandparents, or even great-grandmother losing status. This further opened up the eligibility for status to more people.

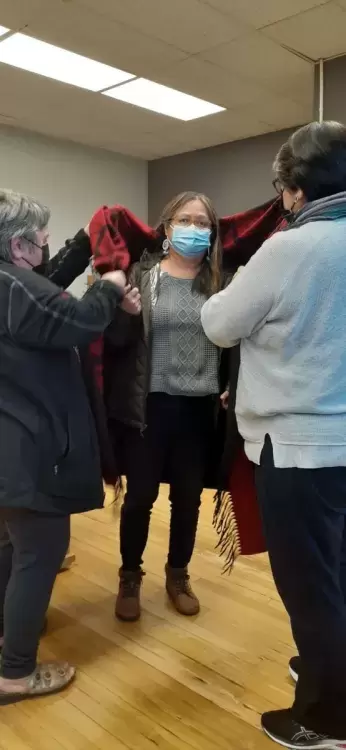

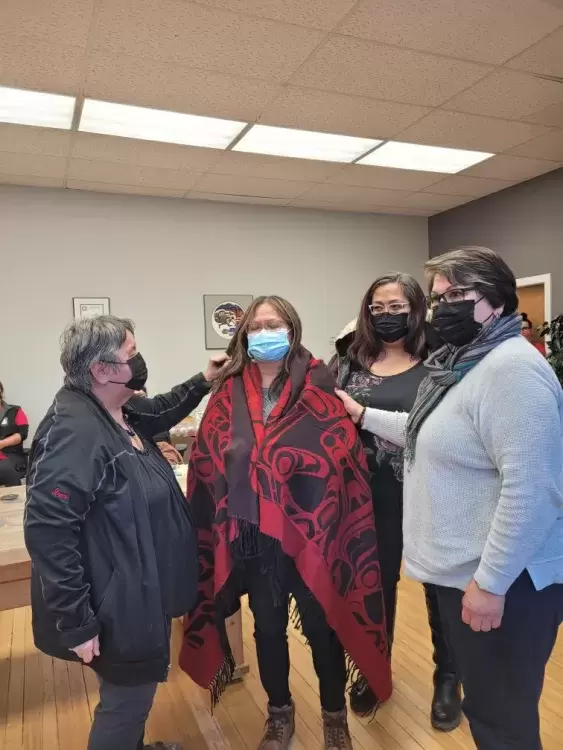

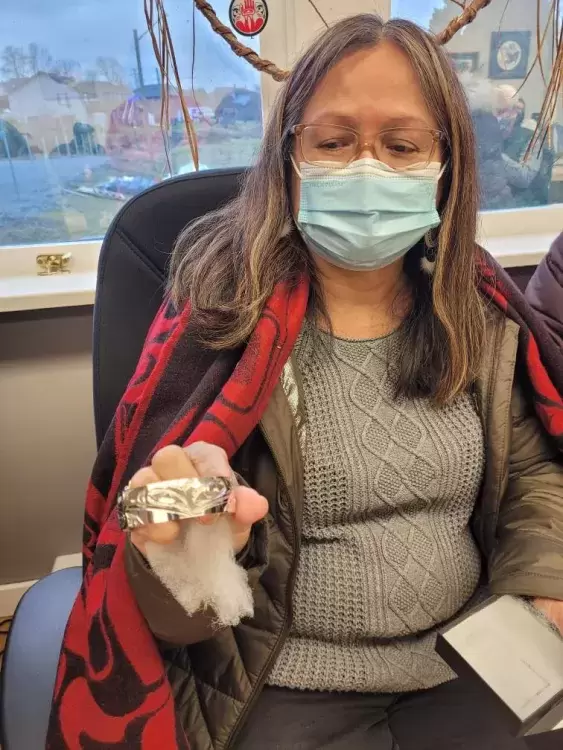

“I really enjoy working with people. I enjoyed it when I went out to the communities, the urban gatherings,” said Marsden, looking back on her career with the tribal council. “I would like to thank NTC and Quu’asa for the send off that I got. I really appreciated working for the Nuu-chah-nulth people, it was an honour.”