Although it took more than two years to produce since the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act was passed in Victoria, First Nations leaders are calling an action plan released today “a step in the right direction”.

In late November 2019 British Columbia became Canada’s first province to put the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples into law, with the passing of Bill 41, or DRIPA. The legislation serves as a commitment for the government to uphold basic human rights for Indigenous peoples in B.C., tasking the province to align its laws with the UN declaration, an international document that upholds the self determination and territorial authority of Aboriginal communities. DRIPA was developed by the province in consultation with the First Nations Leadership Council, a body composed representation from the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs, the B.C. Assembly of First Nations and the First Nations Summit.

More than two years later, an action plan on accomplishing this was unveiled by the province today, detailing 89 initiatives to be undertaken over the next five years. The document emphasizes Aboriginal rights and title over territorial lands, with an emphasis on self determination. Actions include reforming B.C.’s forestry policy to align with UNDRIP, an external review of discrimination in the education system, implementing recommendations from the In Plain Sight report on systemic racism in health care and policing reform that addresses systemic bias in law enforcement.

“There’s some really good recommendations in there,” said Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council President Judith Sayers, after returning from the B.C. legislature, where the plan was presented. “It’s a really good starting point for us to begin the work.”

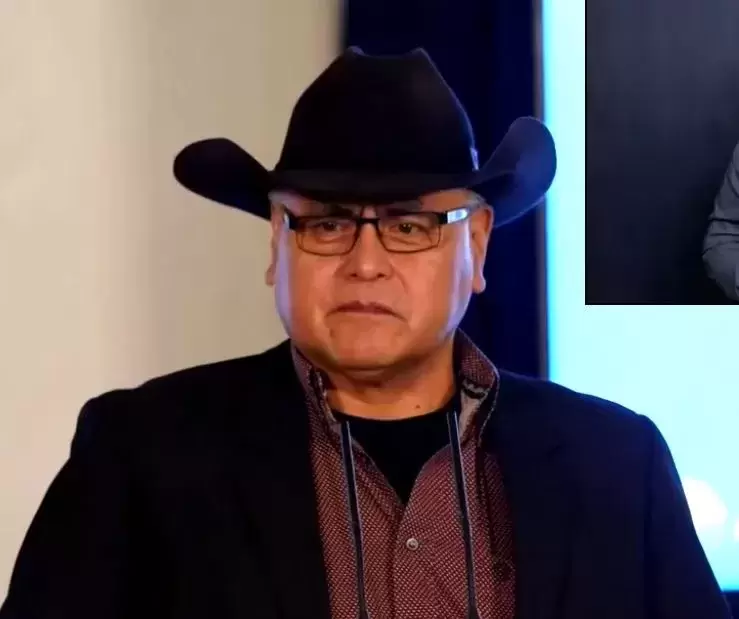

“Today marks a step in the right direction,” said Mowachaht/Muchalaht Ha’wilth Jerry Jack, who spoke on behalf of the B.C. Assembly of First Nations when the plan was announced.

In the wake of the colonial development of B.C. over the last century and a half, the action plan listed inequalities currently facing Indigenous people, including overrepresentation in prisons and the foster care system, lower rates of formal education, as well as higher poverty and unemployment. Other measures detailed in the plan include “concrete measures to increase literacy and numeracy achievement levels” of Aboriginal students and the implementation of the First Nations Justice Strategy, which addresses the growing overrepresentation of Indigenous people being incarcerated.

“We cannot step away from our past - the joys and the sorrows - but we must, we must learn from it,” said Premier John Horgan during the announcement.

“I think together we can change the trajectory or our shared history,” emphasized, Murray Rankin, Minister of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation.

Horgan referenced the history of First Nations being in conflict with the provincial government, something that Chief Jack mentioned as he spoke of the action plan with optimism.

“I went with my dad in the ‘70s to blockades fighting for our land and our rights,” he said. “I don’t want my grandkids to grow up in the struggles I had to have our rights recognized.”

“If we are to be part of the transformational change and face challenges of our generation with integrity, wisdom and love, we must all work together,” added Jack.

The small group of First Nations with a modern-day treaty are highlighted in the action plan, which notes the Shared Priorities Framework signed by the premier and leaders from these eight groups this year to ensure “timely, effective and fully resourced” implementation of the formal agreements. Five of these First Nations are part of the Maa-nulth treaty: the Huu-ay-aht, Toquaht, Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ, Uchucklesaht and Ka:'yu:'k't'h'/Che:k'tles7et'h'.

“Modern treaty nations have a unique and distinct relationship with the province and we are pleased to see the action plan reflects this and speaks to our Shared Priorities Framework,”said Uchucklesaht Chief Councillor Charlie Cootes in a statement.

Although the action plan did not include a recommendation from the NTC to prioritize clean energy opportunities for First Nations, Sayers was pleased to see language on revitalizing wild salmon populations. But it remains to be seen how exactly the province can carry out the ambitious plan over the next five years.

“There’s some good intentions here. But the question is, are we going to get it done? Are we going to do it soon enough?” she asked. “I think it’s going to be up to us as First Nations to keep pushing them politically and moving things faster than they want to.”

When DRIPA was passed in 2019, the province was faced with approximately 5,000 laws that needed to be realigned with the UN declaration. Rankin would not address how many of these laws have been revised so far, but noted that a secretariat is now in place to ensure the responsible adoption of UNDRIP.

“The question will be how we can prioritize the existing laws. Which ones are we going to do first?” said Rankin. “Some of it will not be done, I’m sure, for a generation, but a lot of it will be done right now.”