Unlike the empire that claimed sovereignty over Nuchatlaht territory and other parts of British Columbia in 1846, the Nuu-chah-nulth nation did not document its history with written records.

Although the legacy of habitation on Nootka Island was transferred from one generation to the next orally, other evidence of ancient ties to the remote area can be seen in the forest, which archaeologists and Nuchatlaht members look to as proof their land was stolen when the Crown asserted authority 176 years ago.

This point is currently being contested in the B.C. Supreme Court, where a trial is underway over the Nuchatlaht’s Aboriginal title claim to the northern half of Nootka Island. Although the 20,000-hectare area is considered part of the First Nation’s traditional territory – with several federally recognized Indian reserves by historical village sites – the provincial government is disputing the Nuchatlaht’s claim of continued historical habitation.

The trial hinges on the legal test of proving uninterrupted occupation of the land since 1846, the date that Britain claimed sovereignty of the area, declaring all forest property of the Crown. In a statement filed to the court, the province disputes the Nuchatlaht’s continued use of inland areas, stressing the First Nation’s reliance on fishing.

“The Nuchatlaht at the date of sovereignty and at all material times relied mostly on marine resources and used upland areas to a limited extent,” stated the province. “The claim area includes pervasive geographic features, which historically and at the date of sovereignty and at all material times, limited or prevented access, use and occupation by the Nuchatlaht, such as areas of high elevation, steep and densely forested upland areas, and steep, rocky, exposed shorelines.”

Cedar used from birth to burial

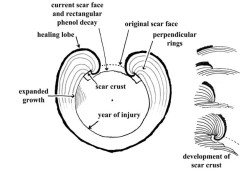

The examination of pre-contact forestry practices has become a central part of the Nuchatlaht’s argument in court. Or particular interest is the prevalence of culturally modified trees – known as CMTs within archaeology circles - which are stands altered by Indigenous people employing pre-industrial harvesting practices. Most CMTs had a long strip of cedar bark peeled off the trunk, showing healing lobes of continued growth on either side of the recessed portion where the piece was removed generations ago. This pliable, tough material was woven into fabric for clothing, napkins or hats, and the bark also provided rope for fishing tools as well as surfaces on roofs.

Philip Drucker documented the versatility of the material in his book, The Northern and Central Nootkan Tribes, published in 1951 from excursions he made to Nuu-chah-nulth communities in 1935 and 1936.

“Products of red cedar bark and yellow cedar bark were used in almost all aspects of Nootkan life. One could almost describe the culture in terms of them,” he wrote. “From the time the newborn infant’s body was dried with wisps of shredded cedar bark, and he was laid in a cradle padded with the same material and his head was flattened by a roll of it, he used articles of these materials every day of his life, until he was finally rolled up in an old cedar-bark mat for burial.”

At least 8,400 culturally modified cedar trees have been identified throughout the claim area, but archaeologist Jacob Earnshaw believes there are many more that are hidden in the forests of Nootka Island or have been logged since the mid-20th century. In his expert witness report provided for the Nuchatlaht trial Earnshaw notes that, although clearcutting was undertaken in the claim area from 1957-2017, archaeological surveys weren’t conducted in cutblocks until 1999.

“Of great concern to archaeological visibility, large areas of the Nuchatlaht claim area were industrially logged prior to the existence of provincial protections for CMT sites,” he wrote. “The majority of Nuchatlaht coastline and forested areas have not been systematically inventoried for archaeological sites. In the few areas that were assessed, dense sites of human occupation and utilization were identified.”

Another issue facing the identification of the Nuchatlaht’s pre-contact forestry practices is the elusiveness of how the trees were harvested. Unlike the industrial standard of clearcutting large blocks of forest, in the past Nootka Island’s residents only took what they needed from the trees, leaving the stands to continue growing. Cedar trees that had their bark stripped hundreds of years ago have continued by producing multiple layers of healing lobes on either side of the harvested portion. Sometimes these trees grow to the point that the bare strip is covered by the lobes completely, making a cedar’s existence as a CMT unrecognizable to many archaeologists performing impact assessment that are currently required under provincial regulations.

Other CMTs had a section of the trunk removed for a plank or canoe. A few found on northern Nootka Island were completely cut high above the base, a logging method that allowed Indigenous people to avoid the wide flares around the roots, a practice sometimes called a “barber chair” that leaves an elevated stump.

Drucker observed that the desirable cedar with knotless trunks often grew back in the woods, where falling an entire tree would “foul those of the forest giants clustered around it.”

“Therefore, the usual procedure was to split a large slab off a standing tree,” he wrote. “This was done by making two cuts, one above the other, the lower narrow, the upper one a high, open notch. The distance between them was that desired for the length of the boards or canoe.”

Using scaffolding to access the upper parts of the tree, each of these cuts were deeply made nearly to the centre of the trunk.

“Then wedges were driven in, downward, in the upper cut until a good-sized pole could be inserted in the split,” continued Drucker. “The logger then went home. After some time the action of the wind rocked the tree and the weight of the cross pole combined to extend the split till it reached the lower notch, and the slab fell off.”

‘Standard practice’ of logging cultural forests

By the 1990s the provincial government began requiring assessments of cutblocks to identify any evidence of these ancient practices. Now the Forest Practices Code of B.C. stipulates the reporting of CMTs and other cultural heritage sites in locations where logging or road building will take place. The Heritage Conservation Act prohibits damage to CMT sites if they show evidence of human occupation before 1846, but logging can continue if a Site Alteration Permit is granted, which requires the documentation of the pre-contact forestry practices.

Earnshaw reported that several Site Alternation Permits were granted for northern Nootka Island - apparently with little resistance from provincial regulators.

“I have not yet come across a Site Alterations Permit, requesting the destruction of a CMT site, having been refused, regardless of the scientific/heritage value of the site identified in accompanying [archaeological impact assessments],” he wrote. “This state of affairs, I would suggest, diminishes the strength of cultural protections for CMTs. The regular felling of cultural forests, including some of the largest on Vancouver Island, appears to have been standard practice in Nuchatlaht Territory.”

John Dewhirst, an archaeologist who has studied coastal First Nations for more than 40 years, also gave a report for the Nuchatlaht trial. Some of the CMTs he lists are dated, usually from the 1800s with one as old as 1543. But Dewhirst states that Nuchatlaht people have been harvesting cedar in the claim area for far longer, as logging and inherent forest processes have made older culturally modified stands unidentifiable.

“Undoubtedly, CMTs have been made in the claim area for thousands of years,” he wrote. “The natural healing process of standing trees has concealed many ancient CMTs from recognition by archaeologists and foresters. The natural forest mortality and industrial harvesting have removed numerous standing CMTs in the claim area.”

Dewhirst cites evidence from Yuquot, an ancient Mowachaht village 20 kilometres south of the claim area, where excavations in 1966 found deposits dating back 4,280 years. “Cultural deposits” were found deeper than where this radiocarbon dating was conducted, suggesting even earlier occupation on southern Nootka Island.

Dewhirst reports that the widespread distribution of CMTs across northern Nootka Island shows “that a body of knowledge based on intimate familiarity of the forest resources in the claim area must have been shared and passed on in the long-standing resident groups there.”

“The only collective group known to have occupied the claim area when the CMTs were made is the Nuchatlaht,” he wrote.

‘We feel our ancestors there’

Culturally modified trees are not the only evidence of pre-contact habitation in the area. Over a dozen burial sites have been identified, half in caves where remains and bentwood boxes were found by surveyors.

Earnshaw’s examinations of the island found sites where houses once stood, their depressions still evident on the forest floor. And multiple shell middens have been documented, thick deposits of garbage indicating the residue to daily life once lived by people in the remote area.

Nuchatlaht house speaker Archie Little will always consider the island home. He spent his childhood in the coastal village of Nuchatlitz before being taken to Christie Indian Residential School at age 6.

“Every square inch of Nuchatlaht Ḥahahuułi was used. Every square inch had a purpose,” said Little. “It’s part of our identity. It’s part of our Ḥahahuułi. It’s part of our lifestyle, it’s our garden, our medicine place.”

He recalls watching the abundantly available herring drying on racks.

“It was our job as kids to keep the crows away with our slingshots,” said Little, who returned to Nuchatlitz during the summer break from residential school.

“We were in heaven, we were free. We were Indian kids again, we were Nuchatlaht kids. We had nobody hoarding over us telling us what to do,” he continued. “We stopped being beaten up for two months.”

Aboriginal title entails the right of a First Nation to use, enjoy and profit from its territory, a legal recognition of ownership that the 167-member First Nation sees as a critical part of its future concerning northern Nootka Island.

“We feel our ancestors there, because there is no better place to go,” said Little. “The kids today, they want to be connected to Nuchatlaht. We want them to be happy, normal, loved kids, and that’s a good place to be to do that.”