By the time Kyle Harry aged out of foster care at 19, he was full of resentment towards the system that oversaw his upbringing since infancy.

“I’m still angry. I didn’t like Usma,” said Harry. “But I’m glad where I come from, from Ehattesaht.”

He recalls living in 12-15 different homes in Ahousaht, Kyuquot, Campbell River and Port Alberni over his childhood.

“Going from home to home to home, I didn’t know where I was going and what was happening to me,” said Harry. “I know how it is for these young ones, how they feel being away from their parents. I didn’t know who my real mother was until I was a teenager.”

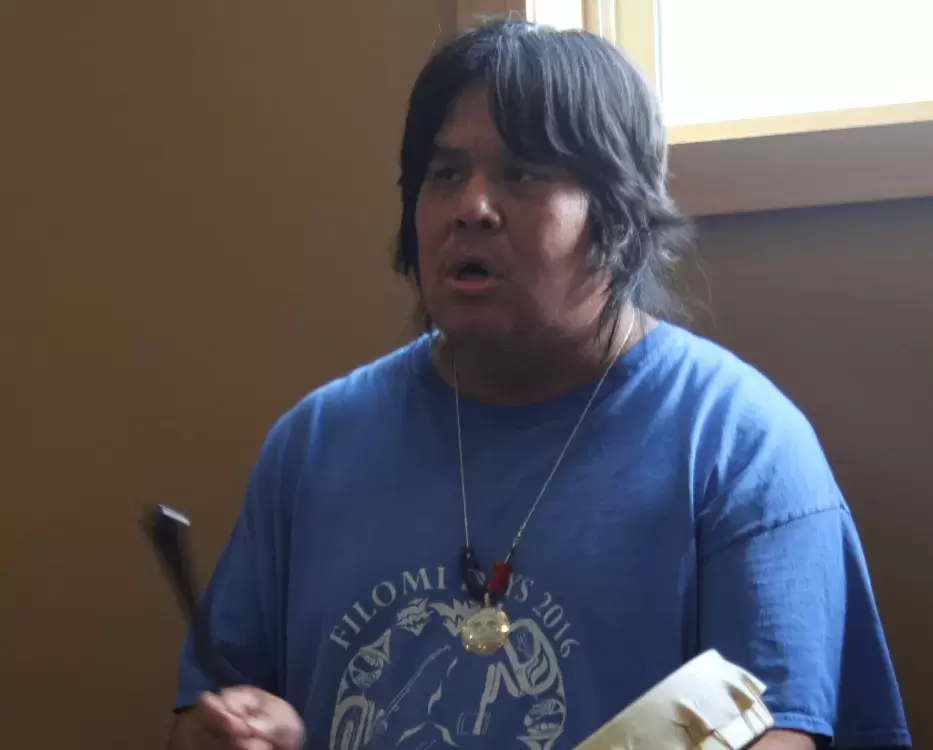

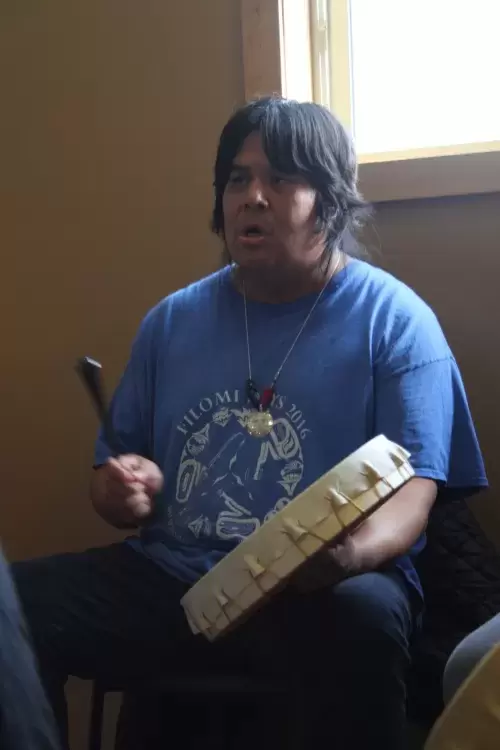

Despite his frustrations with the management of his younger years, Harry, who is now 37, participated in a recent gathering held by Usma Child and Family Services in Port Alberni. One of several taking place for different Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations this spring, the June 6 event brought Nuchatlaht and Ehattesaht members to a venue to spend time with their nation’s children in care. Usma supplies the meal and location, while the nations hold cultural activities.

While a circle of men sang and drummed, girls were provided regalia to wear as the older women demonstrated their ancestral dances. Watching the young ones jump and spin with excitement when the decorative shawls were brought out, Nuchatlaht Health Manager Audrey Smith reflected on the importance of families needing culture for connection and sharing.

As the Ehattesaht’s elder-in-residence, Vince Smith has seen the need for a consistent cultural presence in the Zeballos Elementary Secondary School, which is located right next to the First Nation’s community of Ehatis. Smith contributes his expertise to the school, a valuable influence given the high turnover of teachers that the remote location sees, observed Smith at the Port Alberni gathering. He’s currently carving two totem poles, a process that brings constant questions from students as they visit.

This cultural connection brings a sense of belonging that children in care dearly need, said Kevin Titian, Usma’s Prevention Services Team leader.

“When you look at the whole picture, identity is the core aspect of who we are as kuu’us people,” he said. “What I’ve seen with some of the children is without that identity, it is like they are lost within today’s society, and not really connected to the history of the people they come from.”

“Being away from home was like my parents being at residential school,” reflected Harry, who saw his older brother run away to drink and do drugs as they were continually being moved around. “We wanted to be at home.”

Since Harry aged out of the foster system, the prevalence of First Nations children in care has gone relatively unchanged. In British Columbia the phenomenon has appeared unmovable, as the number of non-Indigenous children in care dropped dramatically from 2000-2020. As of 2020, the number of B.C.’s Aboriginal children in care sat at 3,800 – nearly double the number of non-Indigenous children under 14 in the system.

It’s a cycle that Harry vowed not to repeat with his own children, who are aged 10, 11 and 13.

“I told myself that I would never ever let this happen to my kids,” he said. “That’s how it changed me.”

He believes the main responsibility rests with parents to ensure they are well enough to care for their children.

“It’s not their fault what’s happening, it’s the parents’ fault,” said Harry. “Usma can’t change somebody’s life, that’s what I say, because if they’re going to change for Usma, they’re not changing for themselves.”

A critical part of the gatherings Usma is holding this spring is to connect families with the children in care who desperately need them, said Titian - particularly those youth who live in a group home without a family atmosphere. He found a valuable lesson in the definition of usma, which means ‘precious one’ in Nuu-chah-nulth, but also carries a deeper meaning, according to the agency’s elder’s navigator David Jacobson.

“Usma is the untapped potential of who you are going to become as an individual…we all carry that within ourselves,” said Titian. “The depth of the definition of Usma over the years has been lost. Over the last few years we’ve been rebuilding that.”

Some encouragement came from Ahousaht in early June, when the Maaqtusiis school hosted a potlach. Some children in care where brought to the gathering.

“It definitely was a big success in helping rebuild their children’s identity and helping them connect with family,” said Titian. “It really ignites that little fire inside of them of wanting to absorb more and understand who they are.”