Working toward the goal of zero plastic waste by 2030, the Canadian government announced they’re banning six categories of the most commonly found plastics polluting the country’s shorelines and oceans, but some groups are saying this is far from enough to protect ecosystems and eliminate plastic pollution.

The ban will gradually eliminate the Canadian production and export of plastic bags, cutlery, stir sticks, six-pack rings, straws and some takeout containers.

Canadian plastic manufacturers will have until the end of 2022 to stop production of the newly banned plastics and until the end of 2023 to stop selling them. The ban also ends the export of banned plastics by 2025, making Canada the second country ever to do so. The final ban also closes technical loopholes from its previous draft that would have allowed more durable single-use plastic options to replace items of common use, such as cutlery and checkout bags.

“By the end of the year, you won’t be able to manufacture or import these harmful plastics. After that, businesses will begin offering the sustainable solutions Canadians want, whether that’s paper straws or reusable bags,” said Steven Guilbeault, minister of Environment and Climate Change, in a press release. “With these new regulations, we’re taking a historic step forward in reducing plastic pollution, and keeping our communities and the places we love clean.”

Courtenay-Alberni MP Gord Johns, whose Private Members Motion to combat marine plastics pollution passed unanimously in the House of Commons in 2018, said the government is starting to make small steps to tackle plastic pollution, but far from what’s needed.

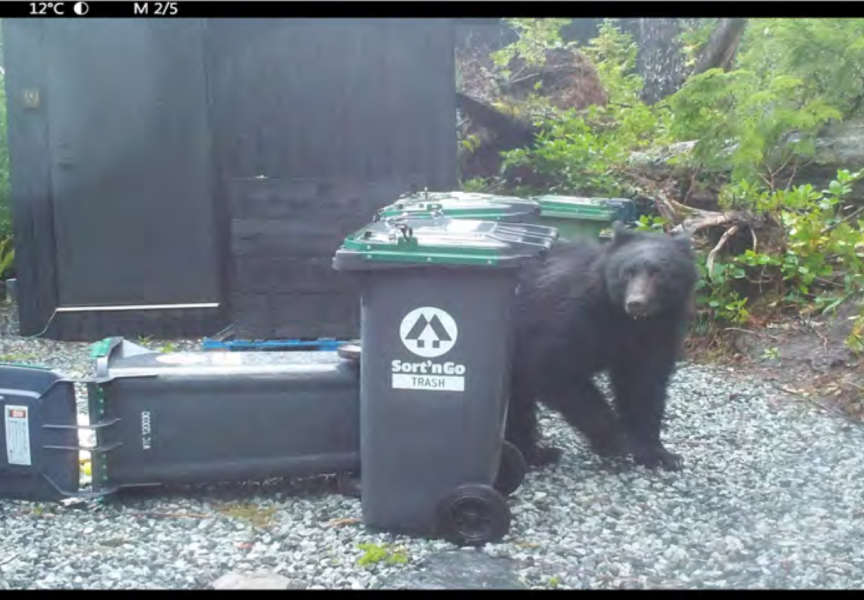

“Plastic pollution in our oceans threatens our environment and human health, it’s hurting wildlife, coastlines, communities and whole ecosystems…it’s concerning and dangerous,” Johns said. “Many Canadians have stepped back, whether it’s using re-usable shopping bags or making changes in their behaviour, but the government needs to go much further.”

Johns said for remaining plastic pollution, the federal government needs a comprehensive strategy that would reduce plastic consumption and remove plastic pollution in and around aquatic environments.

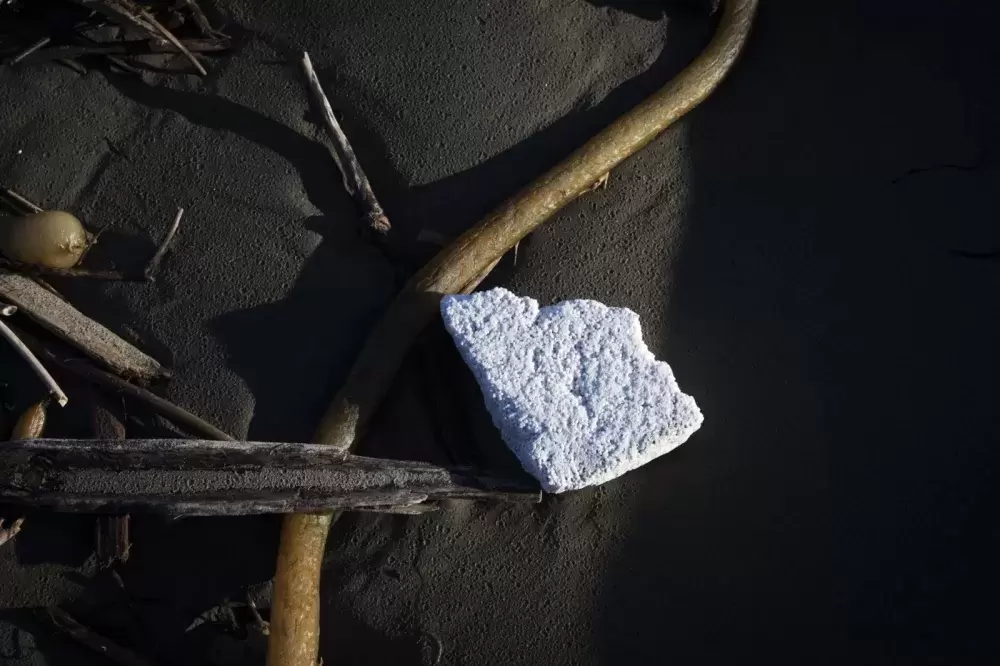

“We’re going to keep fighting to expand the types of single-use plastics included in the ban,” Johns said. “It just doesn’t go far enough. It could have included hot and cold drink cups and lids and all sorts of polystyrene which we know is littering our coast. Those are things [the government] didn’t include which we in coastal communities have been asking for, so it falls short of what we were hoping.”

Polystyrene, one of the most commonly used plastics, is almost impossible to remove from shorelines, Johns said.

“It gets ingested by the wildlife, the fish and goes right up through the food chain, so it’s having a huge impact on the ecosystem and ultimately on human health as well,” Johns said. “We’ve got the longest coastline in the world so we should be global leaders. To take six items and ignore a bunch of others that other jurisdictions have [banned]…in France they got rid of plastic coffee cup lids and plastic cups and Canada can’t do it? Well, there’s no explanation.”

Market research conducted by Oceana Canada, an independent charity established to restore Canadian oceans, shows that 90 per cent of people across Canada support a ban on single-use plastics and two-thirds want to see the proposed ban expanded to include more harmful plastic products.

But in a recent study, the Fraser Institute found that Canada’s single-use plastic ban—the first phase in a goal to reach zero plastic waste by 2030–will actually have little to no environmental benefit while imposing a large financial cost on Canadians.

“Canada’s contribution to the global issue of aquatic plastic pollution is virtually non-existent, but banning plastic—almost all of which is properly disposed of in Canada—will impose high costs on Canadians and will actually result in more waste being generated,” said Kenneth P. Green, senior fellow at the Fraser Institute and author of Canada’s Wasteful Plan to Regulate Plastic Waste.

A press release by the Fraser Institute states Canada’s contribution to global aquatic plastic pollution, when assessed in 2016, was between 0.02 per cent and 0.03 per cent of the global total.

“The government’s Zero-Plastic Waste 2030 plan will only prevent an almost undetectable reduction of three thousandths of one per cent of aquatic plastic pollution,” states the release. “And whatever minimal environmental benefits might be achieved by banning plastic could be offset by the increased environmental harms of the plastic substitutes, including paper products and organic materials.”

According to the Fraser Institute’s study, based on the government’s own analysis, while banning plastic will prevent approximately 1.6 million tonnes of material from entering the waste stream, it will add approximately 3.2 million tonnes of substitute materials for a net increase in waste.

“Instead of banning plastics in Canada, a move that will do virtually nothing to address the global issue of plastic pollution, policymakers should instead focus on improper waste disposal in Canada as a way of reducing what little amount of Canadian plastic that does end up as litter,” Green said in the release.