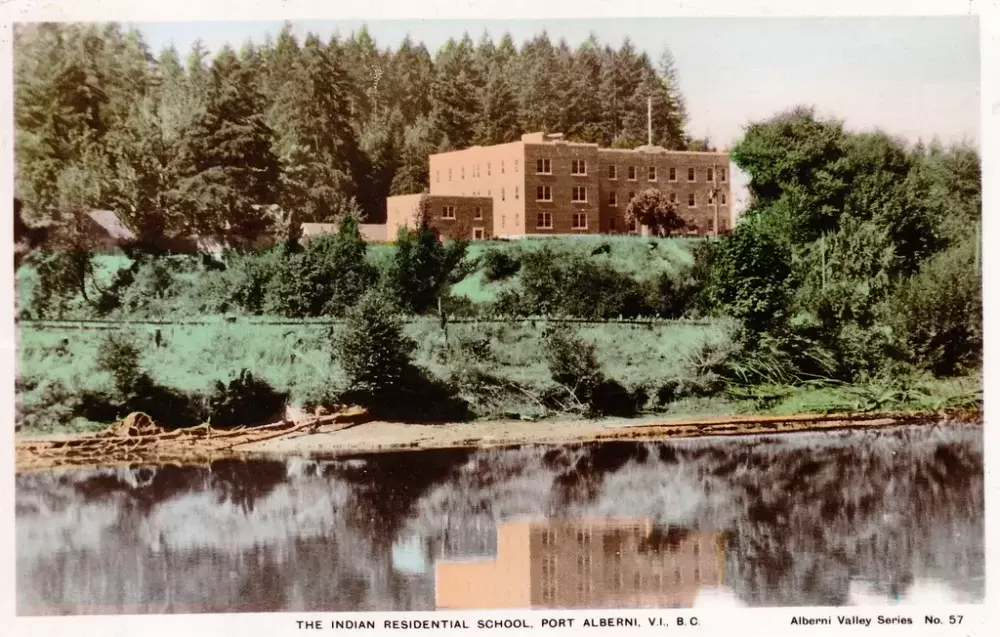

One week of ground-scanning work has been undertaken to identify possible burial sites on Tseshaht territory, bringing challenges in penetrating the rugged terrain that make up the former grounds of the Alberni Indian Residential School.

After months of preparations, including close consultation with survivors from the residential school, possible burial locations have been identified on the more that 100 hectares that used to surround the institution’s grounds for 81 years. The Tseshaht First Nation secured the expertise of GeoScan to analyse the sites, employing ground-penetrating radar technology that has indicated burial sites at other residential schools across Canada. This scanning work began July 11, and is expected to last two weeks.

But Vancouver Island’s terrain has proven to be more challenging that the meadows and fields upon which other residential schools once operated elsewhere in Canada.

“We’ve had to focus our priority areas on areas that we can actually do right now,” said Tseshaht Chief Councillor Ken Watts of the technology. “The grass has to be a certain height. There can’t be huge rocks and sticks and things below it. It makes it pretty limited on what it can and can’t do.”

One advantage of having the residential school on its reserve is that the Tseshaht don’t have to negotiate with private landowners for the radar work to be conducted, as has happened elsewhere in Canada.

“They’ve had to work with private landowners who aren’t as comfortable looking for unmarked graves in their backyards,” said Watts. “It’s really up to us. This is in our backyard, we have to live with it.”

Used in crime scene investigations and archaeological studies, ground-penetrating radar sends high-frequency electromagnetic waves underground. Although this can give a likely impression that a body may be buried in the ground, the technology cannot determine exactly who or what is down there.

“It’s probable that’s what it is based on what the research and the scanning is telling you,” explained Watts of locating possible burials. “The only real way to 100 per cent verify it is through exhuming. We haven’t even had that conversation as a community.”

The undertaking of identifying any burials under AIRS is being led by ʔuuʔatumin yaqckʷiimitqin (Doing it for Our Ancestors), a team of former residential school students, Ha’wiih and elected council members to ensure cultural protocols are followed to the benefit of the Tseshaht community. Although he has heard of other First Nations consider exhuming, the sensitivity of the undertaking makes deep ground disturbance an unlikely approach, said Watts.

“I’ve never heard any of our community members say we’re interested in that,” he said. “In our culture, you’re not really supposed to disrupt those that are now gone, they should be left alone.”

Access to the site of the former institution has been tightly restricted over the first weeks of the scanning process, and the Tseshaht have even had a no-fly zone implemented by Transport Canada over the former AIRS grounds to minimize disturbances.

For generations former AIRS students have known about children who died at the school. Now examination of the site is triggering traumatic memories.

“We’ve had members coming here into our office getting supports culturally as well as clinical counselling,” said Watts. “I think it’s really impacted our community. I’ve heard many stories from people who live around the neighbourhood, spirits and things they’ve felt since then. I think it’s created this awakening in our community.”

After the first two weeks of scanning are completed, the First Nation plans to prepare other areas for GeoScan to return in late August or September.

A full summery report of the work is expected in October.

“This has been difficult, but to move onto the next steps and identify those areas, actually marking them and letting people know the results, it’s going to be hard,” said Watts. “I honestly think that I don’t know that the general public is going to be ready for whatever the results may be.”