This month the Office of the Auditor General of British Columbia reported that the Provincial Health Services Authority (PHSA) did not provide Indigenous peoples in correctional centers with adequate or consistent mental health and substance use services.

In British Columbia, Indigenous people are starkly over represented in corrections centers. With Aboriginal people making up 5.9 per cent of the population in the province, 35 per cent of those in custody at correction centers identify as Indigenous.

Approximately 70 per cent of those in custody have a mental illness and/or substance abuse disorder, while nine out of 10 Indigenous prisoners, between 2019 and 2021, were reported to have been diagnosed with a mental illness or substance use disorder.

The release stated that the PHSA was unable to confirm that upon entering corrections Indigenous people were provided with mental health and substance services, proper assessments, and discharge care plans for release.

Of the 92 Indigenous files reviewed from 2019 to 2021, less than half had complete care plans for mental health and/or substance use, 80 per cent of clients received some services, while 20 per cent of clients received no services.

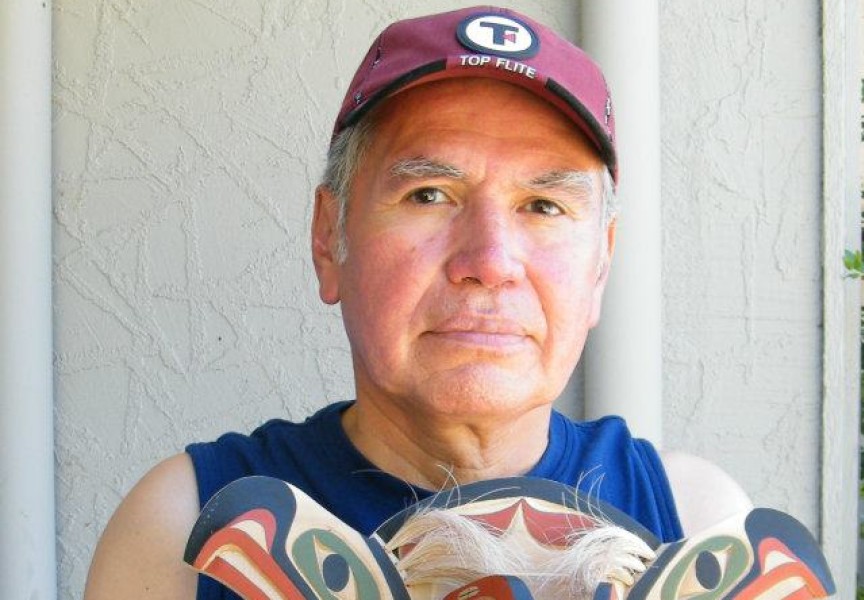

“I think that’s a failing system,” said Elmer Frank, elected chief counsellor of the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation.

“It doesn't make sense just to put somebody in an institution and not offer the necessary support,” he added. “It's just a revolving door.”

Frank explains that some of what Indigenous people face with addiction and mental health stems from colonial violence like banning potlatches and the history of residential schools.

The Auditor General’s press release stated that only seven per cent of the 92 files had a discharge plan, and did not connect Indigenous clients with adequate community resources and health services.

Brett Johnson, founder of One Life Recovery Services, a therapeutic community for men recovering from substance abuse disorder, said, “Most addicted people get that way from traumatic events or the environment they were raised in.”

Johnson stressed that providing people with necessary tools is critical to recovery.

“I think the biggest struggle people are faced with, especially the Indigenous communities and any marginalized persons, is… a lack of resources,” said Johnson.

The Office of the Auditor in General of British Columbia made four recommendations to PHSA.

In response to the Office of the Auditor General of British Columbia, PHSA released a statement indicating their commitment to reconciliation.

“[The] report focuses largely on improving reporting systems, we recognize and accept that the core of the findings is to immediately improve the care provided to Indigenous people in correctional facilities,” stated the PHSA.