A new watershed fund is being heralded as a critical shift in how the provincial government values the natural resource, with particular attention to long-held Indigenous values.

With $100-million to back up its claim, the province announced the Watershed Security Fund earlier this month, with a pledge that B.C.’s future will be different than the past century and a half of reliance on unsustainable resource extraction.

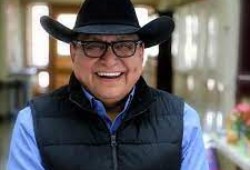

“Todays announcement is an important expression of hope for the stewardship of our watersheds,” said Nathan Cullen, minister of Water, Lands and Resource Stewardship, during a press conference on March 6. “For far too long, too many have taken our abundant freshwater resources for granted. The hard reality is for far too many watersheds in British Columbia, they are facing significant challenges that requires us to take a more ambitious, more strategic approach to ensure the sustainability for future generations.”

The $100-million fund is to be managed by the B.C.-First Nations Water Table, a collective of representatives from the provincial government and Indigenous communities formed in June 2022 to bring in a new strategy to better protect B.C.’s watersheds.

Chief Lydia Hwitsum of the Cowichan Tribes is co-chair of the water table. She called the fund a “significant undertaking and shift in terms of including Indigenous voice [and] respecting Indigenous law.”

“When we work together, we can get better outcomes,” she said.

With the announcement of the fund, the watershed table released an intentions paper to guide the provincial investment. The document stresses the need to align the provincial government’s policies with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, something that the province was tasked to do when legislation put this declaration into B.C. law in 2019.

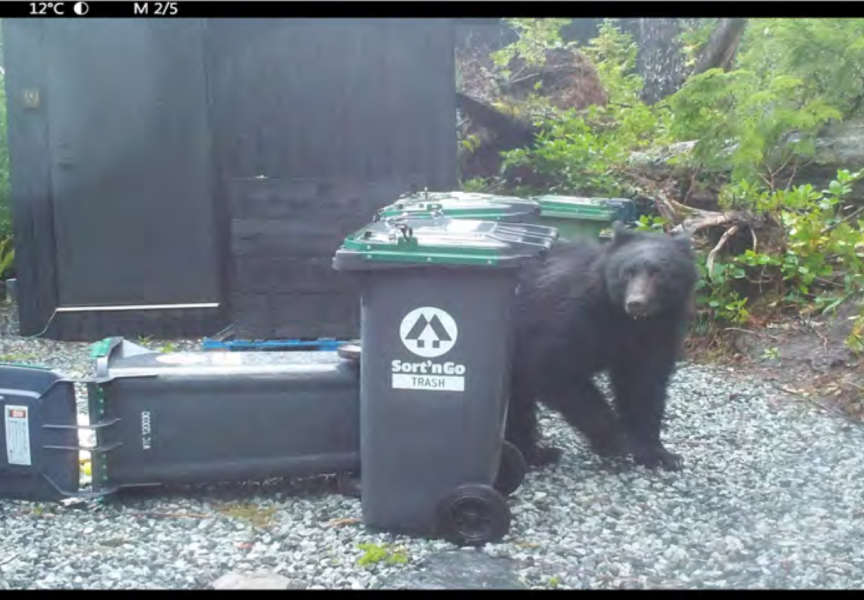

Informed by public input received last year, the intentions paper also mentions the need to build a strong foundation of watershed science that people can access, strengthen regulations to protect the resource, find ways to balance water supply with demand and to “adopt wild salmon recovery as a key value.”

Water table delegate Hugh Braker cautioned that B.C.’s industries can have a competing interest in the water supply, something that will collectively need to be resolved.

“We know that those are competing interests, everybody wants a big share of fresh water, but we also know that we cannot fail,” he said. “We cannot let the province of British Columbia lose its natural resources.”

After droughts over the past few summers and an atmospheric river event that left devastation in parts of B.C. due to torrential rainfall in November 2021, more alarms have been raised recently on threats tied to the province’s water. In March a report from the Canadian Security Intelligence Service was released, warning that the earth’s rapidly changing climate is a serious threat to British Columbia’s coastal communities due to rising sea levels. Global warming also threatens the province’s food security, warned the national spy agency.

While the watershed table’s intentions paper focuses on the ongoing concerns of climate change, Braker, who is a member of the Tseshaht First Nation, noted that other human-caused activities cannot be overlooked.

“It’s not just climate change, it’s also industry, logging industry on Vancouver Island for example,” he said.

Over a century of industrial-scale forestry has left an unavoidable mark on Vancouver Island’s watersheds. Towards the southern portion of Nuu-chah-nulth territory, 62 per cent of the Sarita River watershed had been logged by 1997, according to studies conducted by the Huu-ay-aht First Nations around its river, including 97 per cent of the flood plain.

Further up the coast, similar effects can be seen in the Gold River, said Mowachaht/Muchalaht Hereditary Chief Jerry Jack, who watches many rivers in his territory dry up each summer.

“Our fish are stuck at the waterfront because they can’t go anywhere,” he said during the March 6 press conference, alluding to the impacts of forestry. “They widen the rivers, the rivers get wider and wider and there’s no more water, [fish] can’t go anywhere. It gets really scary.”

During the announcement provincial representatives noted that forestry companies cannot have a future in the industry unless their processes leave a sustainable environment.

“Water is a precious resource, it’s critical to our individual lives. It’s also a limited resource,” said George Heyman, minster of Environment and Climate Change Strategy. “It’s a resource that’s been impacted in often negative ways by practices that came about because we were out of touch with the land, the air and the water in a way that Indigenous peoples in British Columbia could never afford to be.”

“For us, water is a living being - not just to be managed, but to respected and protected,” said Jack, who is on the B.C. Assembly of First Nations board of directors. “Our whalers used to go to the water to prepare to go whaling. Although we don’t whale anymore, we still go there to cleanse ourselves, to make ourselves better for what we’re going to do. If we don’t have that, we won’t have life.”

Another period of public engagement is open for the direction of the Watershed Security Fund until April 17. Then the B.C.-First Nations Water Table is tasked with developing a watershed security strategy over the spring and summer.

Input can be submitted to the watershed security initiative at feedback.engage.gov.bc.ca.