This year two elected leaders stepped away from politics after serving their First Nations for over a generation - time that included the negotiation of one of British Columbia’s few modern-day treaties.

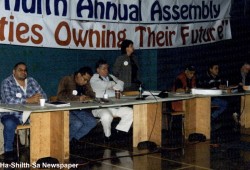

Charlie Cootes and Robert Dennis Sr. were recognized at the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council’s Annual General Meeting for their long terms as chief councillors. Held on Nov. 30 in Port Alberni, the meeting took place days before Cootes stepped away from being the Uchucklesaht’s elected chief on Dec. 11. Dennis completed his last term as Huu-ay-aht chief councillor in June.

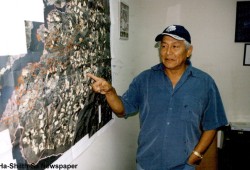

For Cootes, involvement in his nation’s governance has spanned most of his lifetime, starting in 1967, as noted during the meeting.

This was a time when the collective of Nuu-chah-nulth nations was known as the West Coast Allied Tribes, a time when modern-day essentials had yet to come to many coastal communities, recalled Cootes.

“We started out that none of our nations had proper sewar, electricity,” he said.

In 1973 the Nuu-chah-nulth collective would become the West Coast District Council of Indian Chiefs, before being renamed the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council six years later. The early years were a time when the collective focused on bringing essential utilities to First Nation villages.

“In the early years of the NTC we prioritized that money to develop one or two nations every year in one of those categories,” said Cootes during the recent AGM. “We gave them state-of-the-art sewer systems, hydro, water…we did that on a rotational basis for the 14 communities.”

Dennis served half a dozen two-year terms as a councillor through the 1970s and 1980s until being elected chief in 1995, a position he held until 2011, then again from 2015 until this year.

He reflects on a consistent vision of improving the economic prospects of the Huu-ay-aht.

“I got involved because I took the view that previous leaders and elders of our community left us a pathway to follow,” said Dennis. “My grandfather and my dad built a trolling boat when that wasn’t the norm. They built a boat in 1966. That gave the skill that when you want to get things done, get them done.”

Cootes was motivated to improve the community he was connected to.

“What can you do for your community? Not what can you do for me,” said the former Uchucklesaht elected chief. “It’s what you have to do to get people to move back to their communities, take their place and carry on good governance.”

A major accomplishment for the two leaders is the Maa-nulth Final Agreement, a treaty that includes the Uchucklesaht, Huu-ay-aht, Ka:'yu:'k't'h'/Che:k'tles7et'h', Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ and Toquaht First Nations. These Nuu-chah-nulth nations remain the five out of 14 who have engaged in the treaty process since the early 1990s, and are among just seven First Nations across B.C. who have progressed negotiations with the province and Canada to implement a final agreement.

Enacted on April 1, 2011, Maa-nulth brought $73.1 million (in 2006 dollars) in capital transfer payments to the nations, with a total of 24,550 hectares of treaty settlement land. This removed the Maa-nulth nations from the jurisdiction of the Indian Act, giving them full authority, under Canadian law, over their lands and resources.

After at least 15 years of negotiations, when he signed the agreement in 2006 former Indian Affairs minster Jim Prentice said Maa-nulth would “set in motion” solutions to social and economic issues within First Nations that had hindered growth for too long.

“It’s a huge step and I always encourage people to pursue it – if not treaty, then some sort of governance agreement with the two governments,” said Cootes.

Since treaty implementation, the Uchucklesaht Tribe has undertaken major real estate projects in Port Alberni, including opening the Thunderbird Building in 2016, an $8-million multi-use facility near the Harbour Quay that offers 34 apartments, with administrative space for the First Nation. In 2018 the Uchucklesaht bought property formerly used for the Redford School, a 1.5-acre full city block that contains 20,000 square feet of office space, a full gymnasium, a large kitchen and field. Many of these offices are currently being rented by NTC departments.

Down the Alberni Inlet in Uchucklesaht territory, in recent years the tribe has built several new homes in the village of Ethlateese, where about a dozen of its members live year-round. Cootes has seen these sorts of projects happen quicker under the treaty.

“That document gets better each time you read it,” he said. “It shortened our time frame for decisions that used to go to Ottawa by about eight months to two years, we now do in two weeks. That’s how good treaty is, we get a lot done, we make our own laws.”

“Our financial position is significantly greater than before we entered treaty,” reflected Dennis. “It gave us the tools to generate more economy, to generate more revenue, and therefore we had the ability to enhance our programs and services.”

Since Maa-nulth was implemented, Huu-ay-aht has added 1,230 hectares of private land to its holdings. This includes multiple properties in Bamfield, where the First Nation now owns a motel, two lodges, a market, café and pub. The Huu-ay-aht have also claimed a growing stake in forestry in their territory south of Port Alberni, with a 35 per cent interest in Tree Farm Licence 44.

The intention has been for these investments to translate into better services for Huu-ay-aht citizens, said Dennis.

“We needed things in place in order to advance economic development, in order to enhance programs and services,” he said.

But the former elected chief reflects that it wasn’t until 1993 that the Huu-ay-aht were able to assemble a team to progress the treaty mandate.

“As Huu-ay-aht First Nation we were nearly removed from the NTC table because we were poorly organized and didn’t have all of our ducks in order,” said Dennis, noting that the agreement couldn’t have been made if his nation asked for too much. “There were tough compromises. If you see treaty negotiations as lock, stock and barrel, then you have to look at it differently. Huu-ay-aht First Nation looked at it as an opportunity to enhance what we’re doing.”

After negotiations moved forward, Cootes recalls a time when the province and feds wouldn’t discuss things further.

“Robert and I approached them, and they said, ‘No, we’re not going to come to the negotiating table unless you get a really good administrator and really good chief negotiator,” he said.

This ended up being the late Tseshaht leader George Watts.

“We called him and asked him to be our chief negotiator, and that’s the only way the government would start to talk to us again,” Cootes recalled. “We spent the next six years finalizing our Maa-nulth treaty.”

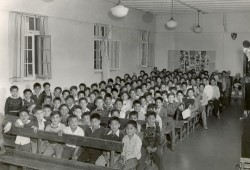

Cootes and Dennis, who are related, first met each other as children attending the Alberni Indian Residential School. With a chuckle Dennis reflects that it was under the strict rules that dominated Indigenous youngsters at the school where he learned how to negotiate.

“When you’re in residential school, breaking rules was always a challenge,” he said. “Getting away with it was even a bigger challenge.”

“Sometimes Charlie would sneak out at night, and I would stay in,” continued Dennis. “When I’d stayed in, he would come knocking on the window, trying to get in. ‘What are you going to give me, Charlie, for letting you back in?’.”

Ahousaht elder Wally Samuel knew Dennis and Cootes since the late 1950s, when they attended the Alberni residential school together.

“We were little boys together, residential school,” said Samuel. “That’s why we are the way we are to survive, to make sure our people aren’t mistreated, put down. We never want those things to happen to our people, what happened to us.”

During the AGM Uchucklesaht Tyee Ha’wilth Clifford Charles reflected on how these childhood survival tactics led to leadership skills in adulthood.

“We hear really bad things about the residential school, the devastation, the sorrow. What was needed to be done was to take the Indian out of the Indian, it almost worked,” he said. “These guys are smart. They’re products of residential school, and that’s the only good thing I can say about it.”