In early May a powerful sun storm made the Northern Lights visible from Vancouver Island, but no one predicted that the resulting magnetic disturbance would have been felt on the ocean floor as well.

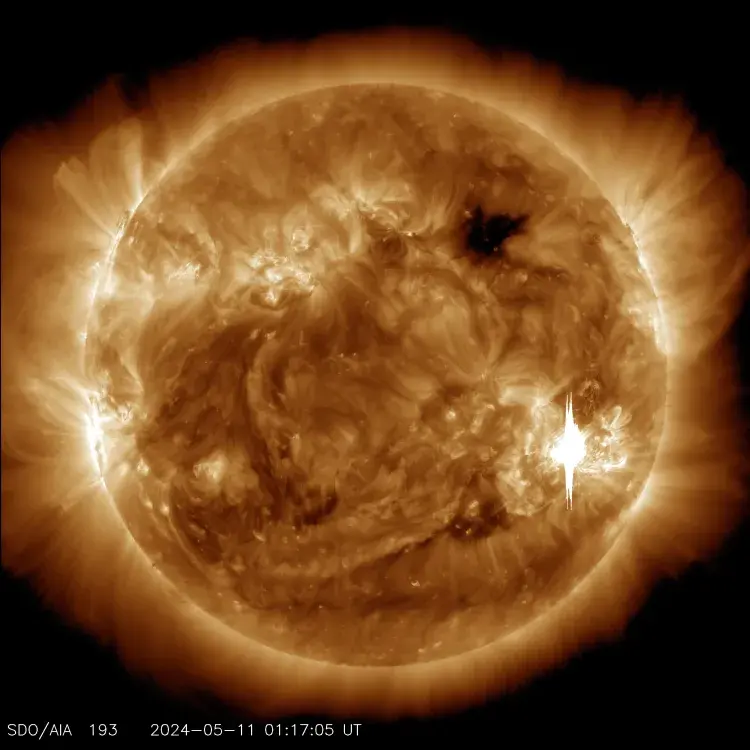

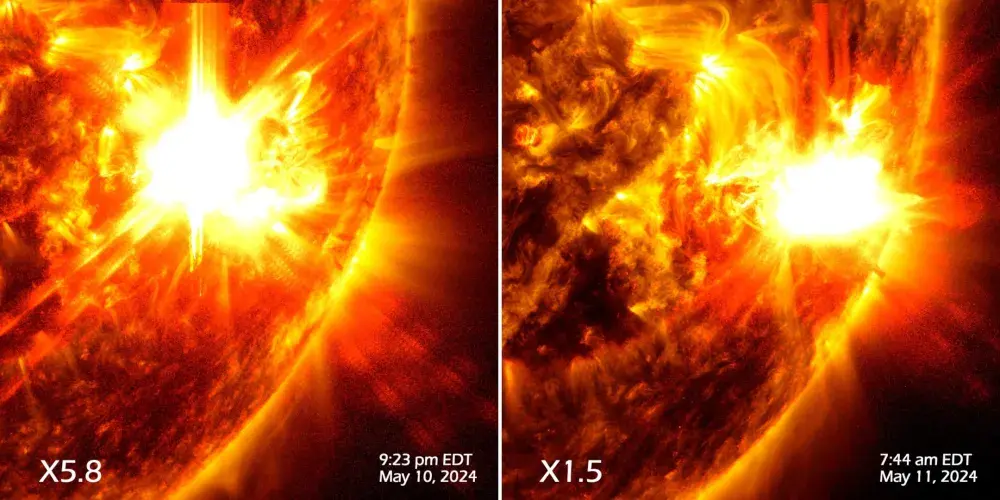

Over the first full week of the month NASA recorded the strongest solar storm to reach earth in two decades. From May 3 to 9 the National Aeronautics and Space Administration observed 82 solar flares, which are giant explosions on the sun that send energy, light and high-speed particles into space.

“[A] barrage of solar flares and coronal mass ejections launched clouds of charged particles and magnetic fields towards earth,” stated NASA on its website.

This generated one of the strongest displays of the Aurora Borealis in the last 500 years. Also know as the Northern Lights, the geomagnetic storm was so strong during the second weekend of May that the nighttime display of light and colour waves could be seen from parts of Vancouver Island.

But over the following days, data collected from the deep sea indicated that the effects of the solar storm could have been felt up to 2.5 kilometres below the Pacific Ocean’s surface.

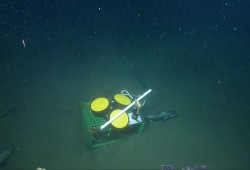

Ocean Networks Canada monitors a series of subsea observatories in the Pacific, Atlantic and Arctic. Instruments called Acoustic Doppler Current Profilers sit on the ocean floor to measure currents, but in the days that followed the solar storm the compasses in these devices had recorded anomalies.

“It has coils in it that can then be affected by electromagnetic field,” said Kate Moran, Ocean Networks Canada’s president and CEO. “The actual change in the magnetic field in the ocean at the location was changing the readings.”

Fluctuations from the compasses were recorded from the NEPTUNE instruments that stretch via a cable network far west of Vancouver Island, as well as from the VENUS profilers southeast of the Island and in ONC devices collecting data in Conception Bay on Canada’s Atlantic coast.

The abnormal readings began Friday, May 10, lasting approximately 24 hours until the following evening. The changes in data were recorded as deep as 2.5 kilometres far west of Vancouver Island, but the largest variation was a shift between +30 and -30 degrees 25 metres below the ocean’s surface at an instrument in Barkley Sound.

“We hadn’t seen it before, ever,” said Moran. “It’s a little bit of a discovery, I would say.”

The changes in the compass data coincided with peaks in the Aurora, leading the researchers to believe that this is an effect of the sun.

“We know that the magnetic field in the deep ocean was impacted by the solar storm,” Moran noted. “The ocean is a conductor, so, of course it’s going to conduct and modify the magnetic field in the ocean too.”

Back in March, after a smaller event on the surface of the sun, an ONC data specialist noticed an anomaly in recordings. He now believes this had the same cause as what occurred during the May solar storm.

“I looked into whether it was potentially a earthquake, but that didn’t make a lot of sense because the changes in the data were lasting for too long and concurrently at different locations,” commented data specialist Alex Slonimer on what he noticed in March. “Then, I looked into whether it was a solar flare as the sun has been active recently.”

Such magnetic disturbances pose a risk to power grids, satellites, navigation systems and even animals with their own magnetic wayfinding abilities.

Some believe this is part of the reason why salmon are able to return to spawn in the creeks where they were born, after years of migrating far into the ocean. In 2020 Oregon State University released findings that the species’ relationship with magnetic fields could help salmon find their way home to breed. In the study juvenile chinook were subjected to a strong magnetic pulse that affects the magnetic orientation in other animals, including mole rats, birds, bats, sea turtles and lobsters. The study found that salmon could be using microscopic crystals of magnetite, an iron oxide, in their tissue as a biological map and compass.

“In the big picture, these salmon know where they are, where they’re supposed to be, how to get there and how to make corrections if needed,” said David Noakes, the study’s author and a professor of fisheries and wildlife at OSU. “While they’re in fresh water, they’re imprinting upon the chemical nature of the water. When they hit salt water, they switch over to geomagnetic cues and lock in that latitude and longitude, knowing they need to come back to those coordinates. And when they decide to come back, it’s months in advance because they’re halfway to Japan.”

While no widespread environmental disruptions have been evident from the recent solar storm, there’s reason to believe that such events will become more common over the next year. The sun is approaching the peak in an 11-year cycle, with the Solar Maximum anticipated in July 2025. The Northern Lights are expected to become stronger and more frequent as this event approaches.