European Green Crab (EGC) are aggressively invading coastal waters and decimating ecosystems in the Pacific Northwest.

This highly effective predator was first identified on the West Coast in San Francisco in 1989 and has been rapidly progressing northward, destroying marine habitats in its wake. Its only known predator is river otters, but eaten in such small quantities, they considered a threat to the crabs.

According to the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, in areas where European green crabs have been able to establish large populations for extended periods of time they have had dramatic impacts on other species, particularly smaller shore crabs, clams, and small oysters. Their digging can have significant negative impacts on eelgrass, estuary and marsh habitats.

With this type of destruction, EGC threatens aquaculture for fisheries in the United States and British Columbia.

“We definitely consider EGC to be a threat to First Nations’ food security,” said Diana Chan, natural resource manager for the Heiltsuk Integrated Resource Management Department. “We’re already seeing their impacts on shellfish populations, and we are concerned about their potential impacts on other species like salmon through their destruction of eelgrass habitat.”

Sadly, because of the massive amount of eggs one female EGC can lay - up to a half million larvae per year - and the vast stretch of water the voracious creatures have occupied, the situation is beyond eradication. Keeping the population under control is the goal of work currently being done by agencies and tribal partners up and down the coast in British Columbia and Washington State.

Largely, trapping and disposing is the predominant method of controlling EGC. However, due to their ever-growing threat over the past few years, several agencies and tribal nations have developed new tactics to help keep EGC to manageable numbers.

In Washington State, Lummi Nation and the Tulalip Tribes are using slab traps, which the Tulalip Tribes created, to attract gravid females. According to Todd Gray, an environmental protection ecologist for the Tulalip Tribes, the trap is simple and works by using an 18-by-18-inch wooden box to create an ideal location for the crabs.

“The premise behind the design of the crab slab is that it simulates a flat rock, or other similar structure with some space under it that provides refuge and cover for EGC,” Gray explains. “Animals can move freely in and out, but EGC will often hunker down under such structures when an ebb tide exposes them, and await the next flow cycle.”

These traps can be used all year round, checked periodically and require no bait, making them very accessible to many communities battling EGC invasions. Chan has employed them with her crews in Heiltsuk Territory where EGC were discovered in 2012. The animal’s numbers have exploded since then, topping out at 1,000 crabs trapped in a day.

Lummi Nation has also employed an underwater drone to help mitigate EGC numbers. It will be used to survey the health of eelgrass beds to quantify the impact of EGC, according to Shawn Evenson, Aquatic Invasive Species Division manager for the Lummi Nation. The drone eliminates the need for underwater divers and allows for more frequent observation of eelgrass areas that constantly remain underwater.

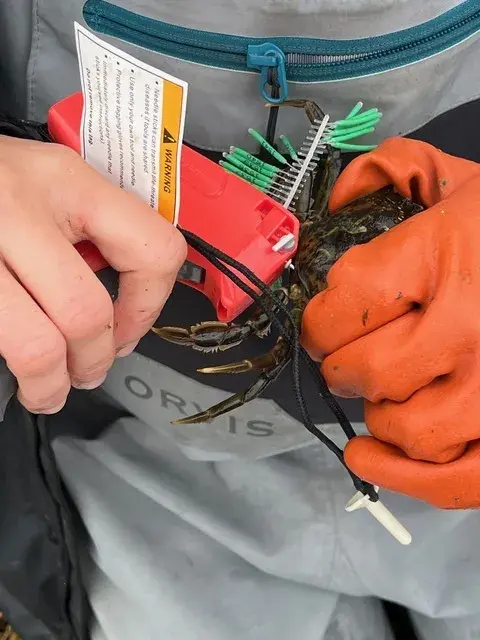

Using a tagging method similar to the price tags used on clothing in stores, biologists with the Makah Tribe near Neah Bay in Washington State are gathering invaluable data that will help them understand movement and survival in order to keep the EGC numbers low. Marine ecologist Adrianne Akmajian and green crab biologist Dawson Little are setting traps on a weekly basis to remove EGC, but separately catching and tagging crabs and releasing them for data. By tagging a small number of EGC (approximately 300 out of 9,500) and releasing them back into the water, they can understand behavior that will help successfully increase their number of trapped crabs.

“We can see changes over the season that relate to both when and where crabs are in the water - up or down river, closer to the ocean - as well as changes in where male and females might distribute,” explains Akmajian.

Understanding where the crab are moving makes trapping them more efficient, as Akmajian and Little work towards their goals of ensuring food and resources for generations of the Makah Tribe to come, while helping the tribe adapt to changes in the marine ecosystem.

The largest number of EGC are found in the Clayoquot Sound and Sooke Basin. Approximately 760,000 EGC have been removed from this area, according to Crysta Stubbs, Science Department director for the Coastal Restoration Society (CRS). Thanks to a massive effort between CRS, Indigenous and federal governments, as well as environmental non-profits, this extraordinary number will hopefully continue to increase, while daily totals decrease.

“Some sites in Clayoquot Sound were close to 10,000 EGC being captured from 40 traps/day at the beginning of the project. Now we’re down to between 1,000 and 2,000 per day in 50 traps,” Stubbs reports.

Teams are dropping traps daily and collecting data that will guide management decisions for the west coast of British Columbia while monitoring how the invasive species is impacting the environment.

“As global sea temperatures rise, we can expect to see a continued northward spread of EGC,” said Stubbs. “They have already reached Alaska and have created self-sustaining populations there. The future of this species will continue to proliferate and cause damage to critical ecosystems and in turn, native salmon, crab and bivalve species unless a significant amount of funding is dedicated in British Columbian waters to manage and control this species."