Editor’s note: The following story contains profanity and reference to child abuse.

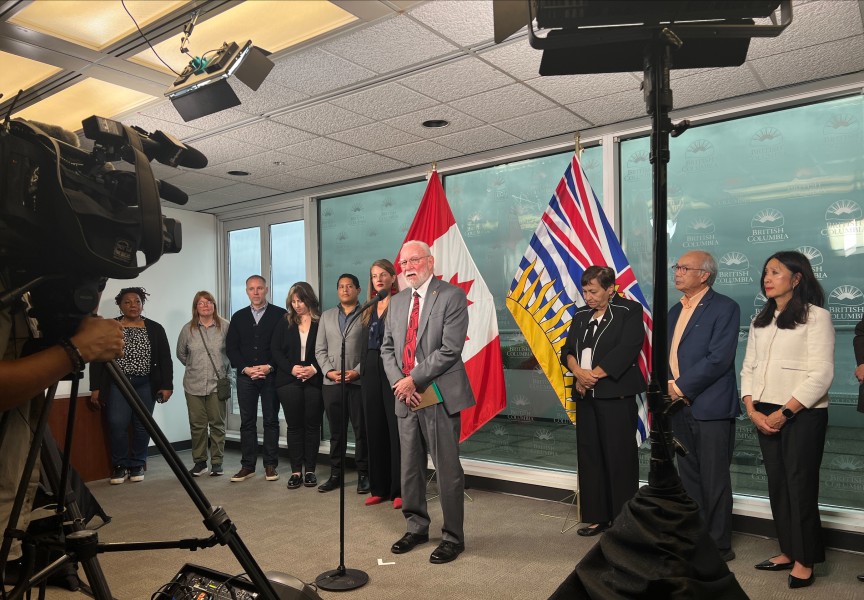

British Columbia’s political landscape has changed overnight, creating a dynamic that has some concerned about how the complexities of an ongoing drug crisis will be handled.

On the Oct.19 election night the Conservative Party of B.C. emerged from the province’s political fringe to come within a percentage point of the incumbent NDP’s share of the popular vote, creating razor-thin results in some polls that prompted recounts over the following 10 days. The latest vote count, which includes absentee and special ballots, has the NDP with 47 seats – the bare minimum for a majority government – the Conservatives with 44 and the Greens winning two. Judicial recounts are still possible for the closest ridings.

If the most recent count holds, the Conservatives will replace BC United as the official opposition in the legislature. The Liberal Party rebranded itself BC United last year, then collapsed before this fall’s election to allow John Rustad’s Conservatives to claim their place in Victoria.

The Conservative’s overnight election success is destined to have an impact on how the government handles the opioid crisis, and policy announcements made this year show that the NDP has already wavered from an approach deemed politically risky. This policy shift includes recriminalizing the consumption of illicit drugs in public spaces and hospitals in May, as well as the expansion of involuntary treatment for those with addiction issues.

More than eight years into a provincial public health emergency, the Conservatives have criticized the NDP’s handling of the crisis, calling it a “chaotic and permissive” approach that prioritizes “short term fixes”. In early October the upstart party released its platform on the issue, titled ‘BC Recovers: A Plan to End the Overdose Crisis and Restore Mental Health Services In BC’.

“The Conservative Party of BC will never normalize drug addiction as a lifestyle choice: it is a cancer that destroys people, rips families apart and leads to deteriorating communities,” stated Conservative Leader John Rustad.

The latest data from the BC Coroners Service reports 1,749 deaths over the first nine months this year. This shows an eight-per-cent decrease in illicit drug fatalities from the same period in 2023, but an average of six people continue to die each day due to overdose.

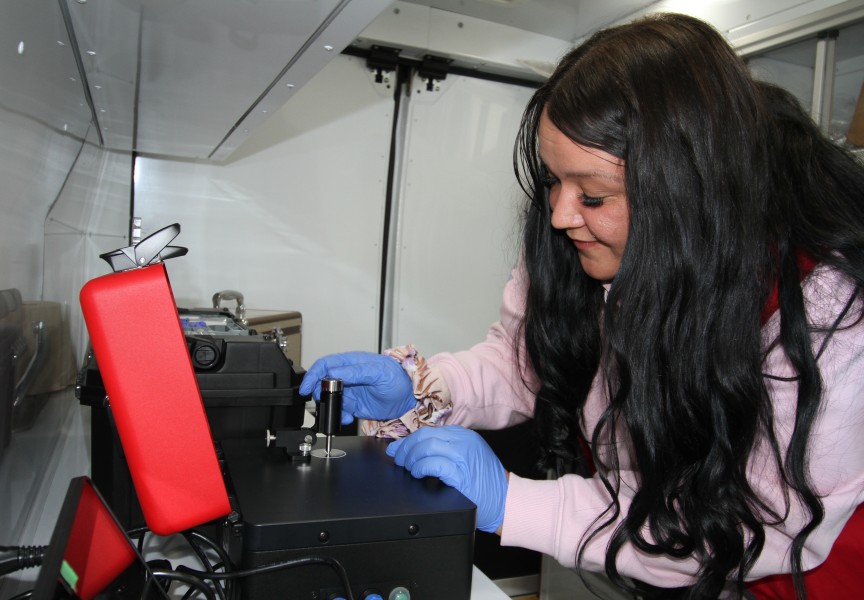

In recent years the NDP has fought the opioid crisis by introducing a three-year decriminalization trial in early 2023 that allows people to carry small amounts of illicit substances. There has also been a push to get more users onto safer prescribed alternatives like hydromorphone. Meanwhile supervised drug consumption sites have grown to over 350 across B.C., where just one death has been reported since the start of the public health emergency.

“The so-called ‘solutions’ of reckless experiments like decriminalization and ‘safe supply’ have done nothing to stop the tragic record deaths, while creating turmoil in our communities,” stated the Conservative election platform, which speaks of restricting safe consumption sites. “As a temporary and emergency measure, some existing overdose prevention sites may be required. Unlike Eby, we will not hesitate [to] shut down any site that refuses to abide by strict standards of conduct. No more free-for-all drug use near schools and playgrounds, no more spilling out onto residential streets.”

The sudden popularity of the Conservative Party of BC has some who are working to manage the opioid crisis concerned. Ron Merk is co-chair of the Port Alberni Community Action Team, a local initiative assembled to tackle the drug crisis.

“I'm really concerned,” said Merk after seeing the election results. “The NDP was more in tuned with the concepts of harm reduction, but clearly they've been told by the electorate of British Columbia that the electorate is not on board.”

“The current political climate is not very favourable,” said Dr. Mark Lysyshyn, deputy chief medical health officer with Vancouver Coastal Health, during an interview with Ha-Shilth-Sa in August. “We’re in a bit of a tricky situation: We need to do more to help people, but the public is not really supportive, even of what we’re doing currently.”

Lysyshyn works in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, an urban neighbourhood that for many years has posted by far the highest rate of drug-related fatality in B.C. He believes that much has been done in the province to help illicit drug users – but it’s not enough, and now Lysyshyn fears that progress could be lost due to public intolerance.

“Recently we’ve been offering services in downtown Vancouver, in an area near Yaletown,” he said. “We faced lawsuits over our overdose prevention site because they feel it’s changing the character of the neighbourhood and harming the residents who don’t use it. People just don’t want to see people using drugs, and they feel entitled to have that view because using drugs is illegal.”

What’s being lost in the debate is the underlying roots of drug addiction, noted Lysyshyn.

“When we think about the causes of addiction, a lot of it has to do with adverse childhood events, things that happened to people when they were very little, essentially not getting the type of support they need at a time when they’re not able to support themselves,” he explained. “These things can happen to anyone, but in our Indigenous community, families have been disrupted and people have been removed from their communities, removed from the places where they get love and support from their communities.”

A crack and crystal methamphetamine user for over 30 years, Richard Anthony Dick is well aware of why he’s addicted. It goes back to his childhood on the Tseshaht reserve in Port Alberni.

“When I was a kid, at the age of 7 and up for six years of my life, I was sexually abused. Both my uncles and one time with their friend,” recalled Dick, who commonly goes by the name ‘Critch’. “I hate thinking about the past period, it really fucks me up.”

Dick’s refuge became clear in his early 20s with the first blast of cocaine through his nose.

“Woah, it was pretty good. It numbed my feelings right away,” he said.

For years Dick blamed himself for being sexually abused as a child, dulling the pain with drugs that are abundantly available in sections of Port Alberni.

“I’ve had good jobs and I’ve lost good jobs because of addiction,” he admitted. “It’s hard to say that we need help.”

As pressure grows to get drug use off the streets, Merk believes that the government and those in public health need to better educate a fed-up public about the complexities of the crisis.

“Somehow, we as a society are separating ourselves from the people that are most marginalized,” he said. “They're not understanding that the root causes of those people standing in front of them on the sidewalk are racism, intergenerational trauma, homelessness, poverty. If we're not willing as a society to address those systemic issues, then they're not going to fix it by thinking that they're going to put those people in jail or punish them in some way.”

Dick wants to kick his addiction, and eventually move to the Tseshaht reserve to be with the family who love him. This fall he’s working on recovery through a residential facility in Surrey.

“It’s my choice to use or not, but it’s my choice to say enough is enough,” he said.