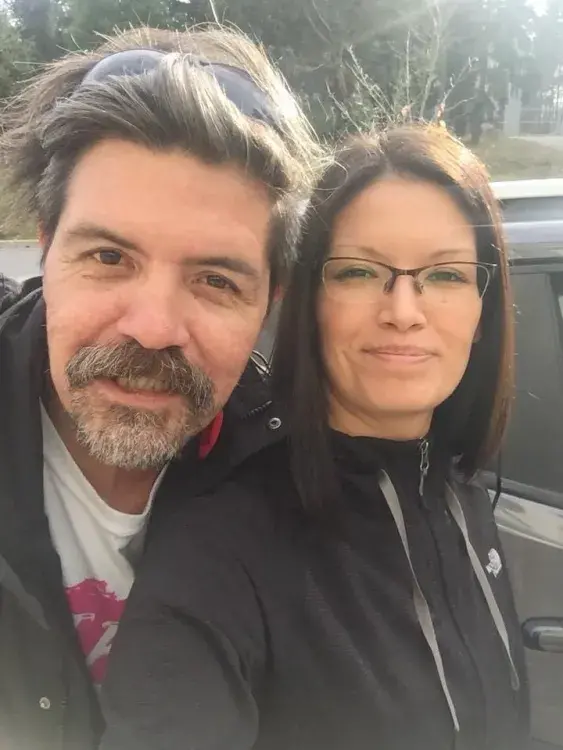

Losing her father in early 2022, Amanda Large thought the grieving process was behind her - until disturbing news came from the BC Coroners Service last year.

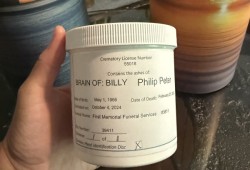

Philip Peter Billy’s brain had been misplaced, and was sitting in the back of a fridge at Victoria’s Royal Jubilee Hospital until it was found more than two years after his death, according to correspondence Large had with the Coroners Service.

Philip Peter Billy of the Ehattesaht First Nation was found unresponsive on Feb. 28, 2022 in his supportive housing unit in Nanaimo. An autopsy concluded that the 55-year-old died the previous day due to bronchopneumonia, a serious infection of the lung, with a severe coronary artery disease that entailed a 90-per-cent blockage.

After Billy’s body was released, the family cremated their loved one in May 2022. Billy’s daughter Amanda was left with Daniel, the youngest of Billy’s five children, whom she had raised since the boy was seven weeks old. Amanda and Daniel decided to put their father’s pictures away, following a cultural practice used by many Nuu-chah-nulth-aht following the passing of their loved ones.

By the summer of 2024 some of Billy’s pictures had been brought out again, but emails began to emerge indicating that the grieving process would not be over for Amanda and Daniel. A message sent to Amanda from a staff member at the BC Coroners Service warns of “a very serious incident brought to my attention that I want to go over with you”, advising her to “please have a good support system in place as this will be some hard and frustrating news.”

The Coroners Service told Amanda that her father’s brain was not with the body when it was cremated, as she had been originally told. Rather, it was still at the hospital in Victoria.

“When it was received by Royal Jubilee Hospital it was misplaced in a fridge and not returned to the body,” stated an email from the Coroners Service. “It was found now while the fridge was being cleaned out.”

“He was supposed to get a second brain autopsy. It never happened,” said Amanda.

“It was very traumatic. I went into nervous shock for two months. I couldn’t sleep,” she added, noting that by early December she fell into a deep depression. “I felt like my dad had died all over again, and it was just much more horrific. He didn’t get to die with dignity.”

Philip Peter Billy did not have an easy life. As a child he went to Christie Indian Residential School, where he was abused, according to what he disclosed to Amanda when she became an adult. Billy struggled with alcohol through his life, and apologized to his daughter for not always being there when she was growing up.

“He was a part of my life, but he wasn’t always there 100 per cent of the time,” said Amanda.

In 2017 Billy had a run in with the police in Nanaimo, which resulted in him being so severely beaten he was hospitalized, recalls Amanda.

“He was riding a bus, I guess he was drunk. They took him and wanted to arrest him. I guess he had one handcuff on and he wasn’t really letting them,” she said. “That really took his health away when the police beat him. He was accused of something, and he was never charged.”

Billy sustained a brain injury, had mobility issues that required the use of a walker or wheelchair, and developed a speech impairment after the incident.

His autopsy notes a history of illicit drug use as well as prescription opioids.

“He had to have a walker,” said Amanda. “He just wasn’t able to keep his health.”

The daughter wanted to pursue legal action against the RCMP after the police incident, but Billy asked her to let it go. But she’s not willing to forgive this recent misplacing of her fathers brain, and has filed a lawsuit against the BC Coroners Service and Island Health for their handling of Billy’s body at the hospitals in Nanaimo and Victoria. Both government agencies have declined to comment on the case, as it is before the courts.

“He had a hard life,” reflected Amanda, looking back to her father’s start in residential school. “He was failed by that system, he was failed by the public safety system and he was failed by the medical system after his death.”

Billy’s brain has been cremated, and the family employed the services of Tla-o-qui-aht elder Levi Martin to perform a cultural reunification of the brain and body ashes. Billy’s pictures were also taken down a second time.

“I do think of him quite often,” Amanda admitted. “Raising Daniel, he has a lot of the attributes of my dad, the way he walks and the things he does.”

“He’s still very much a part of our lives,” she continued. “We did take all of his pictures down, but we put them back up.”