At the height to Tofino’s tourism season, a large crowd gathered by the beach at Tin Wis on Aug. 27 to witness the raising of a totem pole.

Standing 23 feet above the ground, the new totem accompanies another pole of equal height that was raised years ago in honour of former Indian residential school students. The Best Western Tin Wis Resort is owned by the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation, standing on the last location of the Christie Indian Residential School.

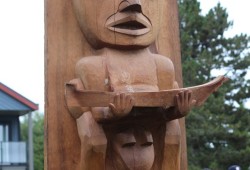

Atop the new pole rests a thunderbird with spread wings, a serpent carved into each. The thunderbird rests on a whale, under which sits a human, representing the late Tla-o-qui-aht hereditary chief Ray Seitcher. Before his passing in 2012 Seitcher worked throughout the coast as a drug and alcohol councillor. On the pole the human character holds a canoe, referencing a gift the late Bill and Joe Martin carved for Seitcher.

“My dad used to speak highly of him, how he was so helpful, and talk about how ‘That guy is a real chief. He’s helping the people’,” said Joe Martin, who guided the project and decided on the characters included in the pole.

Under the man is a wolf, representing the clan that traditionally upheld the teachings of natural law, including community-imposed discipline.

“Back in those days, it was rare that anyone molested a woman or child,” said Martin of when justice had to be administered. “What would happen, is the person would be taken immediately, and the whole village would gather.”

The thunderbird’s chest reveals a crest of the sun, a sign of respect that was traditionally instilled in a person before they were born.

“When mother was carrying them, the elder would sit there and sing this lullaby, so once you were born, they would continue on with that lullaby so the little one was familiar with that. It would make them comfortable,” explained Martin.

“Once you came to the age of about 12 years old or so, when you lose all your baby teeth, then you’re initiated into the wolf clan,” he continued, noting that this applied to males and females.

The totem was carved out of a western red cedar log that was cut down over 20 years ago, and since then lay in the forest by Kennedy Lake. Joe Martin was aware of this stand for years.

“It took me three or four weeks to get it out of the bush,” he said.

After years of applications, $100,000 worth of federal grants came through last October, enabling the project to hire carvers Gordon Dick and Kelly Robinson. Since early February, the pair had worked on the piece at Dick’s gallery on the Tseshaht reserve.

“Joe shared with us what needed to be on the pole, so that’s what we ran with,” said Dick.

Many totem poles that are erected these days are lifted by crane and fixed to a steel and concrete assembly in the ground. But this project was lifted by hand, with six feet of the structure buried for it to stand permanently before the Tla-o-qui-aht-owned resort. It was originally eight feet longer, but a section had to be removed from the top due to breaks and imperfections in the wood.

Dick said that he and Kelly Robinson did their best to work around any cracks in the wood and stabilize the piece. But the carver expects that this challenge will only become more common due to the difficulty in finding quality old-growth cedar.

“That’s one of the challenges that Kelly and I have been talking about for the last decade. The writing is on the wall,” said Dick. “There’s just smaller and smaller pockets of old growth standing or blown down - in this case, cut down and left.”

The new pole is one part of a 10-year, $1.2 million cultural project that Tin Wis has secured funding for. More totems are planned for the beachfront, as are other carvings.

It’s part of continuing an ancient form of communication that once sent messages from one tribe to another along the coast, explained Martin.

“These things were basically teachings of natural law,” he said. “When Europeans arrived, certainly our people were illiterate, they could not read stuff. But I say so were Europeans when they arrived here and seen all these totem poles that used to be in front of our villages. They had no idea what these things were about.”

Martin recalled stories from his father of the four poles that once stood before his family’s house. There was a pair for his grandfather and grandmother, then a pole for his father, which was a combination of the other two, and another for his mother, with content taken from her parent’s poles.

“All of these teachings moved across this coast through this kind of arrangement,” said Martin.

Dick looks to what the pole will mean to future generations.

“I feel that one of the bigger honours is to be part of something that’s going to be here long after I’m gone,” he said. “My little girl and maybe her children will know that I took a part.”